The question of whether chess was invented or evolved from earlier games may never be settled. Part of the discussion is semantic, since evolution and invention are two sides of the same coin! Evolution is a series of new inventions that build upon or combine earlier designs. Inventions are steps in evolution.

Chess rules and customs, even today, are constantly evolving. Through research into old chess literature, I've made some original discoveries regarding how modern rules and customs have evolved to reach their current state. This series will explore some specific rule changes for chess that have evolved over the past few centuries.

Click below for earlier chapters of John McCrary's Evolution of Modern Chess Rules series:

TRIPLE OCCURRENCE DRAW:

Chess players in the 19th century wanted a rule that addressed endless, unproductive attempts to reach mate -- mostly by players who lacked the skill to do so. The 50-move draw rule was one way to deal with this problem, going through its own evolution as a rule to determine when a 50-move count could be demanded.

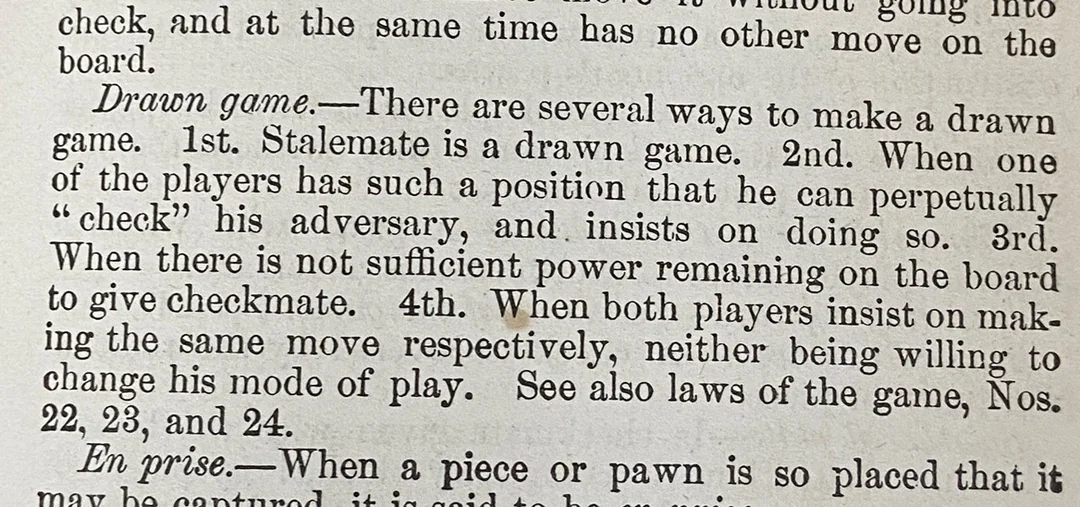

Among those grounds included by English Master George Walker in The Chess Player in 1841 was "perpetual checks, or reiterated attacks involving the same forced moves in answer." Later in 1857, Hoyle's Games: Containing the Rules for Playing Fashionable Games described a similar type of draw: "When both players insist on making the same move respectively, neither willing to change his mode of play."

These early rules were too ambiguous for proper enforcement, however, and later attempts were made to provide clarity on dealing with repeat moves. Adding impetus to the development of these rules was the appearance of time limits in chess games, around the 1860s, since players might force repetitions to gain on the time control.

The Second American Chess Congress in 1871 began with a regulation proposal stating if both players repeat the same move or series of moves five (5) times in succession, either player could declare the game a draw – though this was later amended to three (3) times in succession. The Third American Chess Congress in 1874 continued with that resolution "That a repetition of three (3) moves by each player be declared a draw game, on demand of either.”

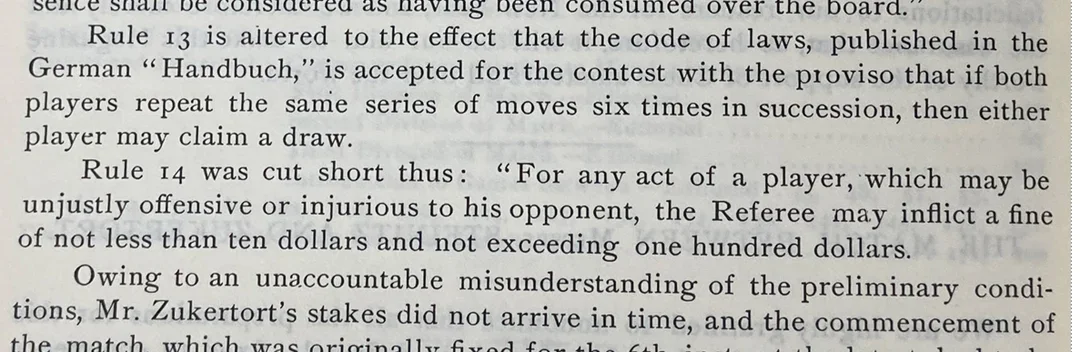

The Programme of the London 1883 International Tournament included this rule, which was later observed by the British Counties’ Chess Association in 1886:

"The Chess rules adopted for the Tournament are the International Code as laid down in the last edition of the German Handbook, with the addition that if a series of moves be repeated three times the opponent can claim a draw."

The ambiguity within this wording is complete, the least of which was precisely defining a "series of moves.” But the London 1883 meetings ultimately anticipated the modern rule, adopting "Rules for Play by Time-Limit" which were then published as the "Revised International Chess Code." Within the London 1883 tournament book was this rule:

"If the same position occurs thrice during a game, it being on each occasion the turn of the same player to move, the game is drawn."

This rule, replacing the vague concept of repeated moves with the more precise concept of repeated positions, while also clarifying that repetitions do not have to be consecutive, was an important step forward. However, this improved wording was slowly accepted, and the two distinct concepts of repeated moves (vaguely defined) versus repeated positions (more-precisely defined) co-existed until the late 1890s.

William Steinitz felt that intentional repetition was a legitimate way to gain on the time control, but observed that, while rules about three or six repetitions might be added to specific tournament or match regulations, the general code of chess laws still used the 50-move rule to cover such situations. For his 1886 World Championship match with Johannes Zukertort, the two players agreed that "If both players repeat the same series of moves six times in succession, then either player can claim a draw."

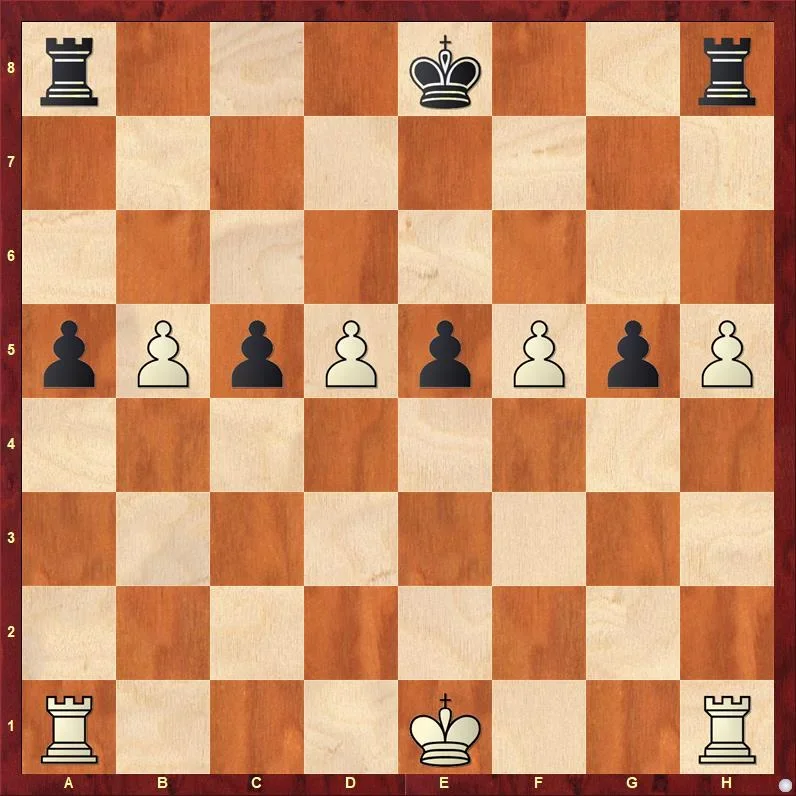

By 1897, published codes of chess laws were consistent in giving the triple-occurrence of positions (not moves) as basis for a draw. The triple-occurrence rule has since been further clarified, defining the identity of positions as including pieces of the same color on the same squares (i.e. two positions might still be identical if White knights are on e4 and g5 in both positions, even if the knights had swapped places in their intervening moves); and the possibility of castling or en passant must be the same. This last provision creates some interesting possibilities where positions may look identical, with the same side on move, but are different because of different possibilities of castling and en passant. Consider the composed following position, with White to move:

This configuration of men can be any of 80 distinct positions, depending on whether both, either, or neither 0-0 or 0-0-0 is legal for each side; and also whether any of the Black pawns moved two squares on the previous move, giving additional possibilities of en passant captures, or no en passant capture if Black's last move wasn't a two-square jump of a pawn.

Many modern players still think in terms of repeated moves instead of repeated positions. I won the 1983 SC correspondence chess championship thanks to a strong opponent's confusing these ideas. He made no attempt to vary his replies to my series of repeated moves, in order to gain time for analysis of a complex endgame. But he overlooked that the position from which the series began had been reached by a pawn move. So the succeeding two series of repeated moves, produced three identical positions. When I surprised him with my draw claim, he first disputed but then acknowledged, while admitting the endgame was probably a draw anyway. I won the tournament by a half-point over him and two others. More recently as a tournament director, I ruled in favor of a disputed triple-occurrence claim, as the opponent had confused the idea of repeated moves with that of repeated positions. A spectator (after my ruling) insisted that it is repeated moves -- until I showed all of them the rulebook!

The 50-move rule and the triple-occurrence rule have some features in common. Applying to both rules are the actions of any capture or pawn move, which not only stop the 50-move count but also break the chain of any past repetition. Also, the complete repetition of a position creates a new position that is not analytically quite the same as the first such position, since possibilities of a draw claim by triple-occurrence or 50-move count will be different in the second such position's total tree of variations.

The two rules differ, however, in two subtle ways. First, if two positions in a game are identical, except that castling is possible in the first position but not in the subsequent identical position (e.g. if the King moves away from and back to its original square); or, if an en passant capture is possible in the first position of a 50-move count (having begun after the opponent's pawn move) but not later in the count -- such differences would prevent the positions being identical for a triple-occurrence claim, but would not interrupt a 50-move count.

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (3)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)