The question of whether chess was invented or evolved from earlier games may never be settled. Part of the discussion is semantic, since evolution and invention are two sides of the same coin! Evolution is a series of new inventions that build upon or combine earlier designs. Inventions are steps in evolution.

Chess rules and customs, even today, are constantly evolving. Through research into old chess literature, I've made some original discoveries regarding how modern rules and customs have evolved to reach their current state. This series will explore some specific rule changes for chess that have evolved over the past few centuries.

Part One: Draws, may be found here.

When (and Why) did White begin to have the first move?

Did you know? Up until the late 1800s, either color could move first in an actual game. Many players had a favorite color that they played, whenever they could. If the players could not agree on the colors they wished to play, then color was chosen by lot. The right to move first was determined separately from color. The "White moves first" rule evolved through a long step-by-step process, beginning in chess literature long before moving into actual play.

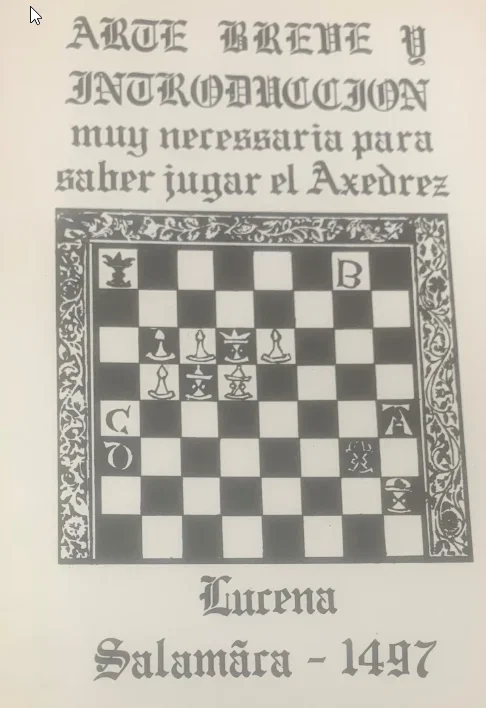

The first step in the evolution of this rule was standardizing the color of squares in relation to the opening position. Early medieval chess used an uncheckered board, which could be placed in any orientation, but soon the board became checkered as a perceptual aid for calculation.

The "white square at right hand" and "queen on color" rules appeared as steps toward this square-color standardization in relation to the opening position, and thus limiting deviations from the opening position. The addition of those rules reduced the number of possible opening position setups on a board to just two, and the resulting standardization of square colors, in relation to the kingside and queenside, helped the reader’s perceptual process.

The standardization of square colors in the opening position, using the "queen on color" rule which placed White’s queenside on the left and the kingside on the right, was an important step toward standardizing the color of pieces in notation systems and opening analysis in later chess literature.

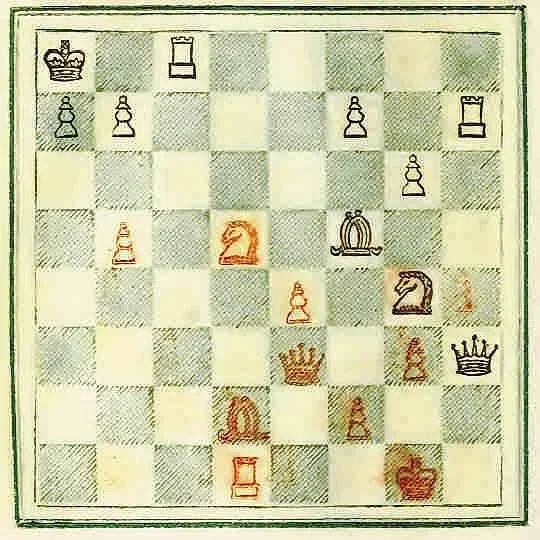

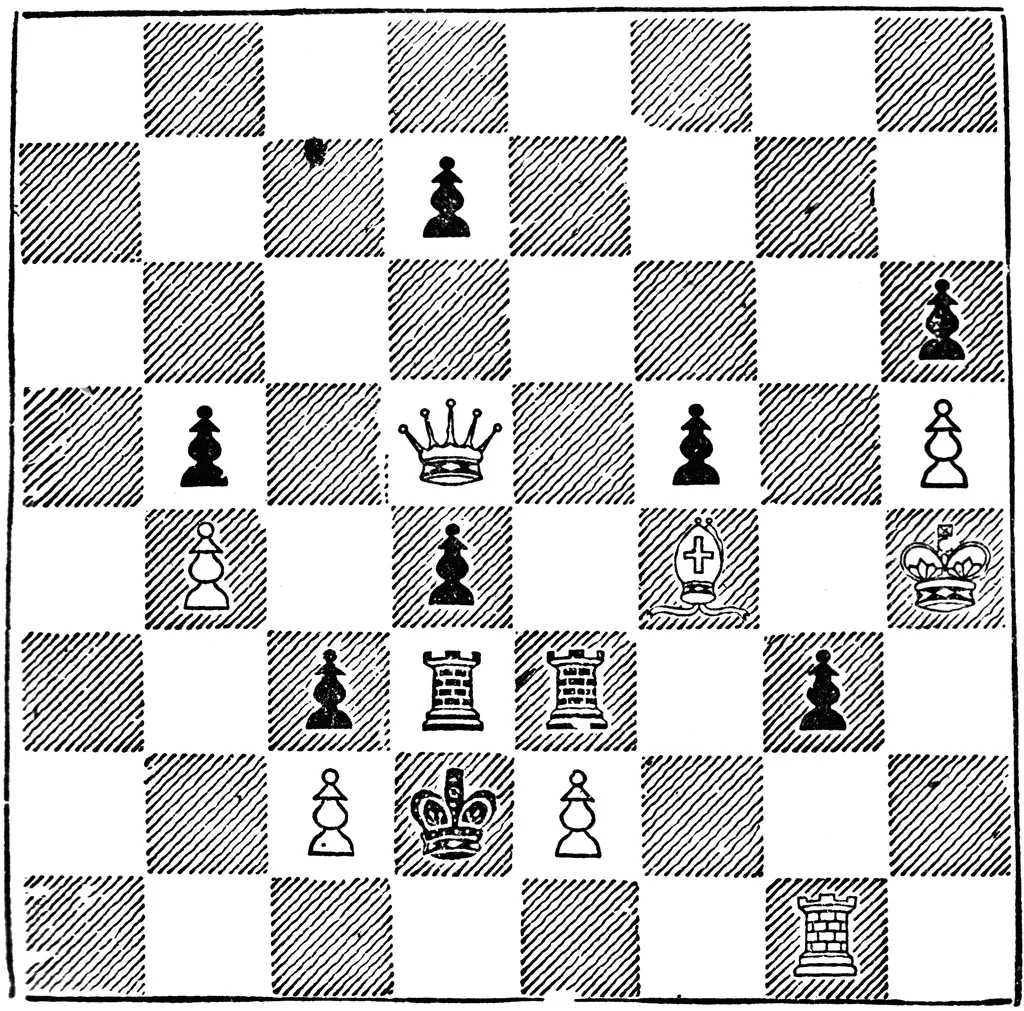

Standardizing the orientation of diagrams came next. To understand which way the pawns are moving, readers need to know from which side of the board they're looking at in a diagram. In very early literature, the standard became placing White at the bottom of diagrams, which in effect, placed the reader on the White side of the board: held upright, the bottom of a printed page becomes the near side, when laid flat; the near side thus corresponded to the readers’ point of view.

Borne was chess notation using White's perspective: since White was at the bottom of diagrams and thus the reader was in White's position, naming squares using White's perspective became natural. In 1737, Philip Stamma, who would become one of England’s strongest masters, was the first to introduce algebraic notation to Western chess.

Stamma wanted each square to have a single name, regardless of which side was to move. So he counted ranks from 1-8 as his pawns would move forward, and he read the a-h files as one would naturally read, from left to right – all seen from White’s perspective. And since he placed White at the bottom of his illustrative diagram, the reader came with him.

In his 1745 book, The Noble Game of Chess, Stamma said:

In all these directions, I reckon forwards from the White; but should you choose to play the Black, turn the Plate, and remember that then the Order of the Alphabet is inverted, as well as that of the Arithmetical Figures...

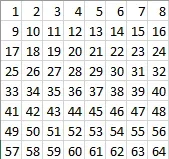

There were other notation systems used in the early 19th century which also gave each square a unique name, as seen from White's perspective. The Elements of Chess, which circulated Boston in 1805, numbered all 64 squares moving up each file in order. No. 1 was the square we now understand as a1, and above that 2 and 3. That made b1 number 9, and c1 was 17. The 64th square was h8.

An Easy Introduction to the Game of Chess, introduced to Philadelphia in 1817, used a different way of naming squares in White's perspective: numbered as though they were being read like a book, from left to right, and moving down line by line. This placed the No. 1 square in the top left, today’s a8, with 2 as b8, and 3 as c8. The final 64 square was at the bottom right – in White’s perspective.

There was other early 18th-century literature standardizing color in a different way, giving White to the reader regardless of which side moved first in examples. Ercole del Rio, an influential author and lawyer in the mid 18th century, used an Italian descriptive notation, admitting:

I have given the player with White the conduct of the game; Black is always the adversary.

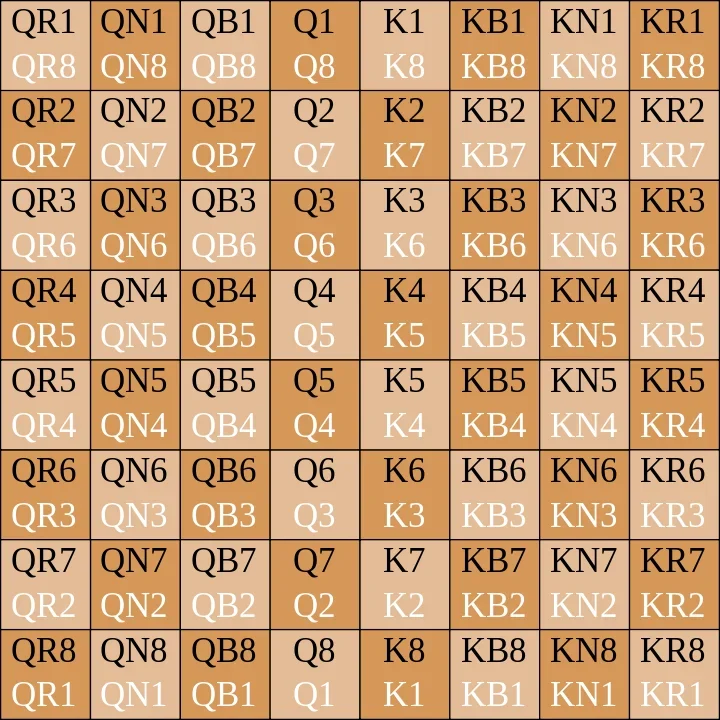

One form of descriptive notation in the early 1800's gave each square a unique name by naming squares by the piece nearest to it on the file in the opening position. Thus, e4 was the White King’s 4th, and e5 was the Black King's 4th, using a system where squares were not numbered just from one perspective.

By the middle of the 19th century, descriptive notation had taken the general form it was to keep until the 1970s: each square had two names, being numbered from each side of the board, depending on whose move was being made. In this descriptive form, neither color's perspective was favored – though White remained at the bottom of diagrams.

Of course, it would have always been possible to simply designate sides as "first player" or "second player" without reference to color, and then name each square from the first players’ perspective in notation. Such an approach would have sufficed – as long as the reader was always refreshed of which color had moved first in the discussed position.

But psychology teaches that we perceive the visual aspects of a phenomenon before applying other learned concepts. So the standardization the color in both the orientation of diagrams and the naming of squares began as a perceptual aid to the reader of chess literature, the student, particularly where that literature was presenting different openings and thus different positions, and not flowing through a single game.

With the orientation of the reader now standardized, White receiving the first move in a composed position became a natural next step. Printed diagrams showed White at the bottom and thus, in effect, placed the reader in White’s position, natural was having White to move in perspective of the position.

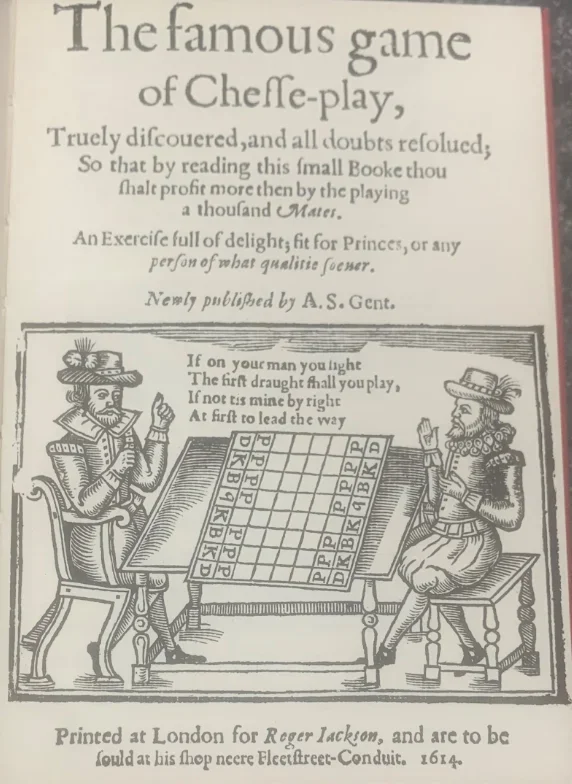

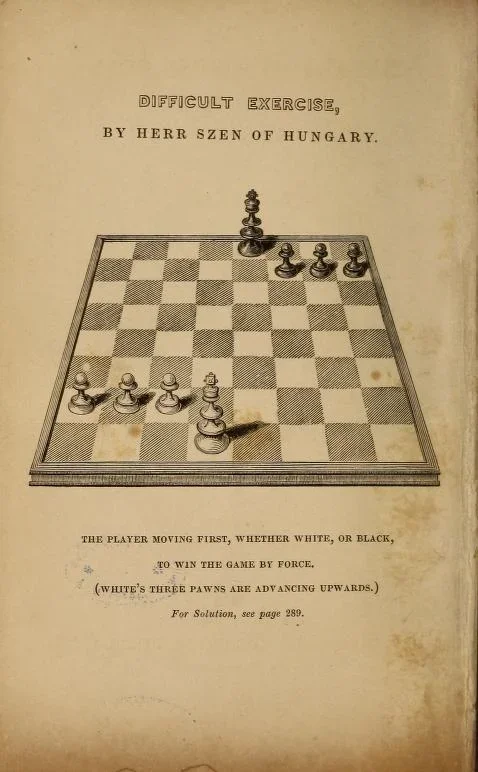

Since composed positions, such as puzzles, problems or studies, are not necessarily from actual games, the composer could arbitrarily designate colors – or adhere to a standard. Stamma in his Noble Game of Chess had White to move first in all composed positions. Lambe's History of Chess in 1764 and the Stratagems of Chess in 1818 used algebraic notation and also had White moving first in all composed positions.

George Walker declared “It is to be understood that White has always the first move, unless otherwise expressed” in his New Treatise on the Game of Chess in 1833. Along with Howard Staunton in The Chess-Player's Handbook in 1847, the two works used descriptive notation counting ranks from each side, but nevertheless had White with the move first in all composed endgame examples and problems.

At the same time, the perception of White moving first was translating in opening analysis. Openings are defined by their characteristic moves, and those moves must be given representation using a notation system. In keeping things simple, there needed to be just one way of designating the defining moves of an opening.

In 1745, Stamma was classifying openings by name and, needing to standardize which color moved first in order to define unique square names for his opening nomenclature, used algebraic notation. By choosing White to move first, he could define each opening by its defining moves, acknowledging the Queen’s Gambit as 1. d4 d5, 2. c4, without having to add the reverse perspective “if Black moves first.”

In 1833, George Walker in A New Treatise on Chess provided illustrative games of his variously named openings. Although he used the form of descriptive notation that counted squares without favoring one color, he wrote:

In the course of this work, I have invariably addressed my observations to White, and have spoken in the third person of Black, as being White's imagined antagonist.

Thus, the idea of the reader being White, having been placed at the bottom of diagrams, was becoming standard even where the notation system did not require. In A New Treatise On Chess, Walker expressed the standardization principle clearly:

For the sake of that uniformity so desirable and essential towards progress on the part of the learner, our battle is always opened by White … I invariably suppose White to have occupied at starting the lower half of the Board, in every part of my work, therefore, White's pawns are moving upwards.

Staunton, however, in the Chess-Player's Handbook, made it clear that in 1847 there was not yet a translation of White to move first in actual game play, writing:

… in all the analyses which follow, the reader will be supposed to play the White pieces and to have the first move, although, as it has been before remarked, it is advisable for you to accustom yourself to play with either with either Black or White, for which purpose it is well to practise the attack, first with the White and then with the Black pieces.

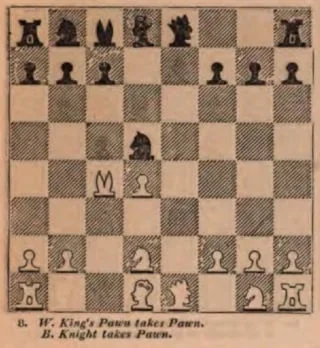

The publication of actual games, distinct from opening analysis or any composed position, was becoming more common by the mid-1840s. The problem posed, however, that if Black moved first in the actual game, the published record of the moves would be complicated by White having accepted the first move in now-standard opening analysis. And there were inconsistencies.

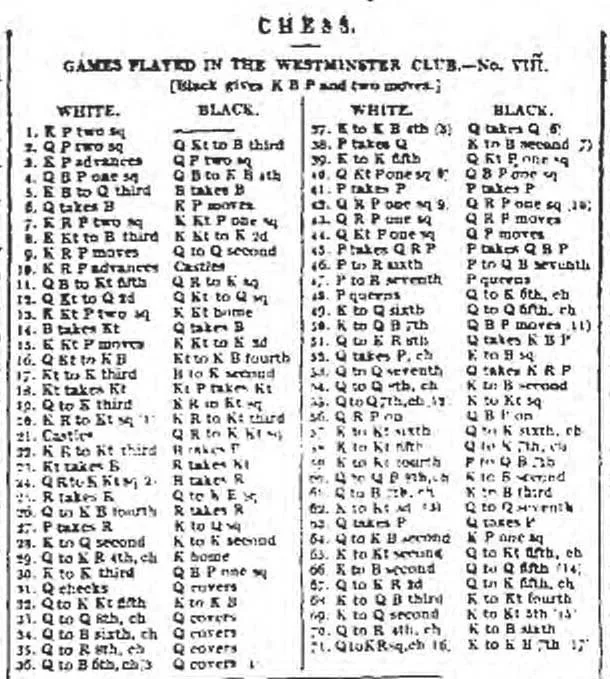

The first English-language chess periodical was George Walker's The Philidorian in 1838, which includes 13 real games. White has the first move in 12 of those games, though there is no explanation of the one exception. In 1844, Walker went on to publish a major pioneering work: Chess Studies, Comprising One Thousand Games Actually Played During the Last Half Century. The work featured no annotations or diagrams, and Walker felt he could avoid the issue of which color moved first in the actual games, stating:

All allusions to colour, as 'White' and 'Black', are omitted, as needless in a work of this description; so that both colours may be called into action, to 'open the ball' by turns."

Since the book used descriptive notation counting ranks from each side, his grouping of games by opening caused no difficulty in the notation.

Howard Staunton was inconsistent in how he used the "White-moves-first" convention in publication of actual games. His Chess-Player's Handbook in 1847 consistently had White to move first in actual games between named players that were given to illustrate his analysis of specific openings. Unlikely that White had actually moved first in all those games, they were undoubtedly presented in the White-moves-first convention to match the opening analyses they illustrated. But in the tournament book of London 1851, Staunton shows Black moving first in games where this actually occurred.

In 1859, the Book of the First American Chess Congress had White moving first in all published games from this event, even when Black moved first in the actual game. Hungarian master Johann Jacob Lowenthal sent a communication to the Congress suggesting that all published games show White as moving first, regardless of which color moved first when the game was played. The books of the Second and Third American Chess Congresses omitted colors in the headings of published game scores, and the notes referred to the first-mover as White.

Before long, the new standard made its way into the actual game. As noted above, before around 1880, either color could legally have the first move in an actual game (as opposed to published analysis, published games, and composed problems and studies, where White-moves-first was becoming standard). Some early writers advised players to accustom themselves to use both colors, rather than staying with a favorite. Players typically kept the same color through a series of games, even when the first move changed.

But the convention of White-moves-first in openings literature started to push chess players toward a rule of making White move first in actual games. In Chess Praxis, published in 1860, Staunton stated this clearly:

Many players have a preference for using the White Men in games where they have the move...This arises partly from the attack being always played by White in elementary treatises on the game, which gives the student a tendency to adopt the same practice....the constant use of White Men in playing the attack is a custom which might give a player considerable trouble, on an occasion where it was not conceded by an adversary.

The earliest appearance I found of a rule requiring White to move first in actual games occurred in a team match in Paris in 1849, where White automatically had first move. But there was still some back-and-forth: at the first international tournament in London in 1851, Black moved first in many games. And as late as 1862, the British Chess Association rules required players keep the same color through a series of games at one "sitting,” even though they alternated the first move each game.

In 1880, the Fifth American Chess Congress defined the rule as “the one having the move, in all cases, to play with the White pieces" and this rule apparently was observed by U.S. clubs thereafter. But England was slower to adapt, the London 1883 international tournament allowing either color to move first – though its tournament book has White moving first in all published games, regardless of which color had moved first in the actual game.

Finally, in 1897 the American and British Chess Codes agreed in giving White the first move in all actual games "in the absence of agreement to a different effect.” The White moves first rule for games was officially standardized in the 1931 Official Laws promulgated by FIDE.

Click here to jump to Part Three: Castling in John McCrary's historical series on the evolution of modern chess rules.

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (4)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)