The question of whether chess was invented or evolved from earlier games may never be settled. Part of the discussion is semantic, since evolution and invention are two sides of the same coin! Evolution is a series of new inventions that build upon or combine earlier designs. Inventions are steps in evolution.

Chess rules and customs, even today, are constantly evolving. Through research into old chess literature, I've made some original discoveries regarding how modern rules and customs have evolved to reach their current state. This series will explore some specific rule changes for chess that have evolved over the past few centuries.

Part One: Draws, may be found here.

Part Two: White Moves First may be found here.

CASTLING

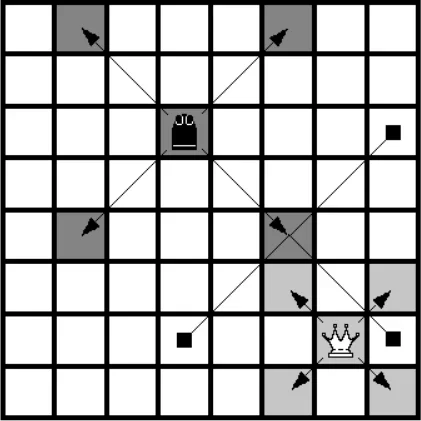

The castling move is a descendant of the "king's leap" in Medieval chess, when the king on its first move was allowed two squares in any direction, including like a knight, leaping over any man in its way. In medieval chess, the king was afforded these safer ventures, on account that the queen and bishop were weak pieces. The queen could move only one square diagonally and the bishop, even weaker, could only move exactly two squares diagonally - thus only able to reach a maximum 8 of the 64 total squares. (These two weak pieces still exist in traditional Chinese chess, which is still played by millions though China also now promotes our international chess.)

The queen and bishop assumed their more powerful modern moves around 1475, though the king's leap remained. With greater threats on the board, now the king sought safety in the corners, and some players used the king's leap for this purpose. They first moved the rook to f1, and later had the king leap over the rook to g1, in effect castling in two moves. The idea later became our modern one-move castling maneuver.

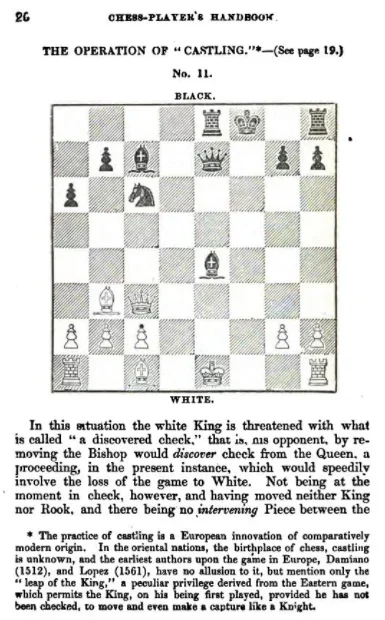

There had always been restrictions on the king's leap, varying among local regions, and some of these restrictions were applied to castling. Most agreed that the king could leap or castle only on its first move, and couldn't leap out of check. Some didn't allow the king to castle if previously checked, regardless of if it had moved or not. Others did not allow castling if the rook crossed an attacked square, while some argued the king should be allowed to castle through an attacked square.

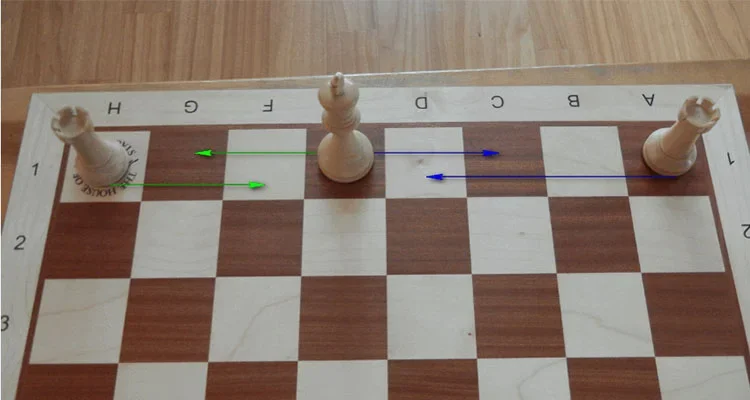

At the beginning of the 19th century, two very different versions of castling existed in different areas. While the traditional rules of castling became prevalent, in parts of Italy and Germany a form of castling was allowed that gave the player freedom in choosing the placement of king and rook. In this "free castling,” the king could go as far as the corner square, and the rook could leap over it to as far as the king's square -- essentially a players’ choice as to which squares the king and rook would occupy. Naturally, the queenside provided even more variations of this method than the kingside, together totaling 16 unique ways to free castle for each player. Because of this greater number of castling variations, a rule was added that, in free castling, neither the king nor rook could attack a piece.

Needless to say, free castling wreaked havoc on opening theory, with each side having 16 possible castling moves – and its impact was felt. In 1800, influential author and lawyer Ercole del Rio observed that the Italian manner of free castling was richer in stratagems, and differed from the other method by being better for offensive designs rather than king safety.

But as chess literature became more abundant and worldwide competition more frequent, these differences in regional castling rules proved a roadblock in making chess a fully international game. There were attempts to satisfy both methods: In the 1840s, a two-game correspondence match between two German cities, Hamburg and Breslau, allowed free castling in one game, but used our modern castling rule in the other game – catering to the preferred method in each city. In the game with free castling, both sides castled the king to the b-file and the rook to the c-file.

In the 1840s, Howard Staunton campaigned to eliminate the free-castling rule, as part of his efforts to standardize international laws and opening literature. As such, free castling began to disappear and ultimately became extinct, though there remained some awkward wording in the published rules that needed clarification.

Early rules stated that castling was possible with a rook that has not been moved. One particularly thorny published trick problem showed the White king on e1, with f1, g1, and h1 vacant, and a White pawn on a7. The "solution" was 1. a8 = R, followed by a castling move that switched the promoted rook from a8 to f1. The argument for this trick problem was that the promoted rook on a8 had not yet been moved so, according to the rules, it could be involved in the castling maneuver! Modern wording has taken care of this loophole, now specifying that the king moves along the same rank toward the rook, which is then transferred over the king.

An additional issue remained, however: could castling be a legal move in a composed problem or study? Castling is not allowed if the king or rook have previously moved, even if they have returned to their starting squares. But composed positions show no preceding moves, so some argued that, if a White king and rook are shown on e1 and h1, castling is still possible because it is assumed they have not previously moved.

But some early composing tournaments barred castling in a solution, on the grounds that one could not assume preceding king or rook moves in hypothetical games. A compromise was accepted: castling in a composition was allowed, only if the composed position could have been reached in any legal game in which neither king nor rook was moved.

But even that convention left one quirk: Suppose the king and both its rooks are on their starting squares, presuming that either 0-0 or 0-0-0 is possible in the solution. But consider this set position: White to move, and Black with only the following: King on e8, rooks in each corner, and three pawns all on their starting squares. Such a position could have been reached only if the Black king or one of its rooks moved last. Thus, either (or neither) 0-0 or 0-0-0 might be legal, but not both. I am not aware of any accepted convention to determine which possibility would be allowed in that case!

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (8)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)