The question of whether chess was invented or evolved from earlier games may never be settled. Part of the discussion is semantic, since evolution and invention are two sides of the same coin! Evolution is a series of new inventions that build upon or combine earlier designs. Inventions are steps in evolution.

Chess rules and customs, even today, are constantly evolving. Through research into old chess literature, I've made some original discoveries regarding how modern rules and customs have evolved to reach their current state. This series will explore some specific rule changes for chess that have evolved over the past few centuries.

Click below for earlier chapters of John McCrary's Evolution of Modern Chess Rules series:

STALEMATE:

Although the concept of stalemate had long been recognized as a different result to checkmate, there was no universally accepted rule on its significance before the 19th century. Through different regions and times, the stalemate rule evolved through one of the following: 1) stalemate was an illegal position, 2) stalemate was a win -- or half-win -- for the player delivering the position, 3) stalemate was a loss for the player delivering the position, or 4) stalemate was a draw.

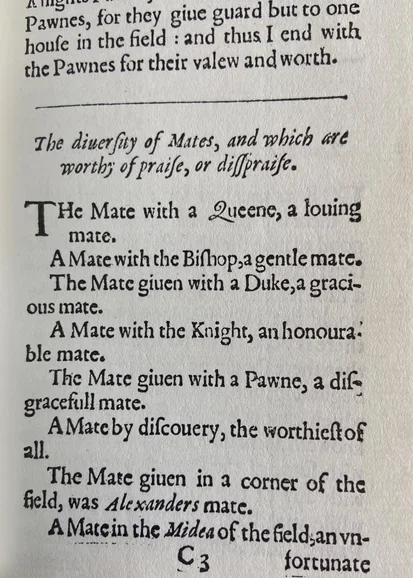

In his book The Famous Game of Chesse-Play in 1614, Arthur Saul wrote a chapter titled "The diversity of Mates, and which are worthy of praise, or disspraise," and the section was pertinent to both his attitude and the influence on the stalemate rule.

Saul referred to a mate in the corner as Alexanders mate. He called mate with the queen a loving mate, while mates with the “duke” (rook) were gracious, the bishop gentle, and with the knight, honourable. And he referred to checkmate by discovery the worthiest of all.

Saul also implied criticism with the delivery of two specific mates. Any mate that was not recognized by the player delivering it was referred to as a blind or darke mate. He noted that some considered a blind mate as a loss by the giver, but Saul called it a valid checkmate -- despite its being "shameful."

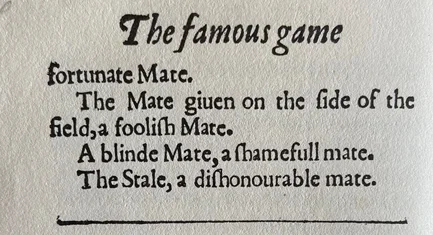

And in Chapter XV, Sault writes "a stale is very dishonourable to him that giveth it" adding:

"... A stale is a lost game by him that giveth it, and no question to be made further thereof.”

He concludes by saying that players who give stalemate "purchase unto themselves such shame, which will not after be put away without much blushing."

John Barbier’s reprint of The Famous Game of Chesse-Play in 1640 had a similar section on the "diversity of Mates,” but with some change in adjectives: mates by the queen became "gracious," and the knight, "gallant.” In the mate section, Barbier also included "The Stale, a dishonourable Mate,” adding that stalemate is a loss for the giver, because

"he hath unadvisably stopped the course of the game which is to end only by the grand checkmate."

Barbier went on to state that a stale is a "Monstrous mate, that is, a mate, and no mate, or end of play, but no end of the game." In other words, Barbier thought the player giving a stale should be punished with a loss, because he'd prevented further play in a game before it was properly ended. However, despite “stale” being the only type of mate on his list that was not a checkmate, Barbier’s inclusion of “stale” on his list of “mates” helped influence the term “stale-mate” in later English chess literature.

English master Philip Stamma in 1745 composed a position in which White wins either by checkmate or by forcing self-stalemate, depending on Black's move. Peter Pratt was still defending that stalemate was a loss by the giver in 1805, saying it was reasonable to have a rule that helped the weaker player, presumably since the possibility of giving stalemate was more likely for the player with the stronger position.

Other ideas around the time thought that differentiating between giving stalemate, versus being stalemated, added another challenge to skill. The idea that a player could win by forcing a self-stalemate was put forth in some English literature as a legitimate stratagem, considering several different endgame scenarios where a player might even "win by a stale.”

The rule that stalemate would be a loss for the giver hung around in England and the U.S. until the early 1800s. Elsewhere, stalemate was evolving into a draw, though some regional variants was referring to stalemate as a win for the giver.

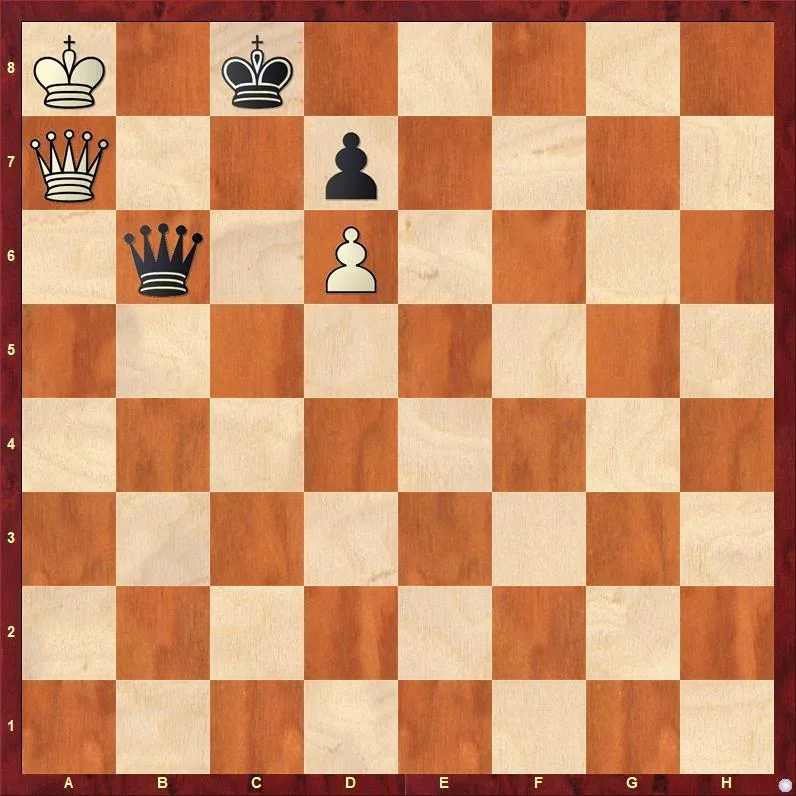

Highlighting the difference between rules, consider this position:

White to move can play 1 Qxb6, which stalemates Black, or 1 Qxd7+, which forces Black to stalemate White. Using our modern stalemate rules, both options will draw regardless of which side is stalemated. But under the rule that stalemate is a loss for the giver: Qxb6 loses, while Qxd7+ wins! And using the variant that stalemate is a win for the giver, now Qxb6 wins, while Qxd7 loses!

Some English books were advocating the standardization of stalemate as a draw as early as 1808, a suggestion that generated much debate, but by the mid-1800s, stalemate had become a draw everywhere.

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (10)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)