The question of whether chess was invented or evolved from earlier games may never be settled. Part of the discussion is semantic, since evolution and invention are two sides of the same coin! Evolution is a series of new inventions that build upon or combine earlier designs. Inventions are steps in evolution.

Chess rules and customs, even today, are constantly evolving. Through research into old chess literature, I've made some original discoveries regarding how modern rules and customs have evolved to reach their current state. This series will explore some specific rule changes for chess that have evolved over the past few centuries.

Part One: Draws, may be found here.

Part Two: White Moves First may be found here.

Part Three: Castling may be found here.

PAWN PROMOTION

Throughout the known history of chess, the only direction a pawn has been able to move is forward. The only variable left was what happened when a pawn reached the final rank, and various promotion rules existed in different regions. In India, a pawn could promote only to the piece that had originally occupied the file it had reached: h-pawns promote to rooks, g-pawns to knights. Another variant included a promoted pawn making a "joy leap" back to its starting square. In traditional Chinese chess, pawns do not promote, though they can move sideways through the opponent's half of the board.

In medieval Western chess, pawns could promote only to a queen – a weak piece at that time, with only the ability to move one square diagonally. But when the queen assumed her modern abilities around 1475, a pawn promoting to the now-powerful piece had a significantly increased impact on the game.

By the 1800s, two main rules on pawn promotion co-existed. One rule limited promotion only to a piece that had already been captured. Thus, a player could never have two queens or more than two of any other piece. If no pieces had been lost, plausible in some openings, the rule was that the pawn remained suspended on its promotion square – unpromoted – until a piece was captured.

Thus, these suspended pawns posed a unique threat as a "wild card" of sorts, creating situations where players were reluctant to capture, especially if the capture meant instant reincarnation due to the presence of a suspended pawn. Additionally, if the opponent had any choice of capture – say, two different pieces caught in a fork -- the presence of a suspended pawn even further complicated the decision.

Many considerations were influenced not just by suspended pawns, but even pawns that were nearing promotion. Since a suspended pawn was ordered to promote to the first captured and available piece, hurrying a sacrifice exchange had additional strategic benefit: forcing promotion to a minor piece and not waiting for a stronger piece to leave the board first. Other strategic quirks in the rule saw benefits in sacrificing a major piece, just to have it available for promotion on a following move.

Modern rules now dictate that a promoted pawn becomes the new piece at the end of its move, so it cannot move with its new status before the opponent’s reply. But some rules in the first part of the 1800s played that a suspended pawn, upon being promoted, could not move until each player had moved once more. This, however, created the equivalent of a temporarily "pinned" piece – though with nothing pinning it.

Other rule variations even allowed a suspended pawn to move immediately as the new piece, in effect earning promotion and then moving again – both before the opponent had the chance to reply! Ercole del Rio, an influential Italian author and lawyer in the mid 18th century, favored this rule of promoting "only to lost piece," and provided this opening variation illustrating the effect of a suspended pawn and its sudden promotion.

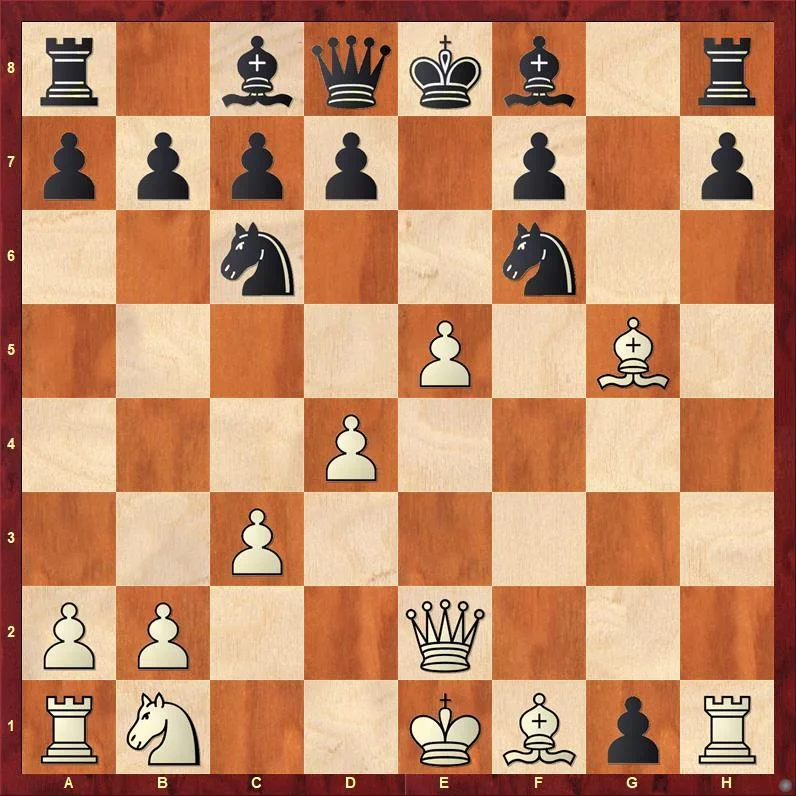

Del Rio’s variation represented a player gaining two consecutive moves: the first action places the new piece on the promotion square, and the second action moves that new piece -- both actions in a single turn. The variation is as follows: 1 e4 e5; 2 Qe2 Nf6; 3 f4 exf4; 4 d4 Nc6; 5 c3 g5; 6 g3 fxg3; 7 Bxg5 gxh2; 8 e5 hxg1 -- and the pawn is suspended on g1, since no Black piece has been captured. Now, White would be amiss to capture 9 exf6+, abruptly transferring the captured knight to the suspended g1-pawn before its move, and allowing Black to play 9...Nxe2!

Compositions using these promotions only to lost pieces helped expose some absurdities behind the rule. Around 1800, German-Austrian master Johann Baptist Allgaier composed a position that showed White leaving two pieces en prise during a series of checks – though the presence of a suspended pawn meant neither capture was allowed, because promotion left Black in check with White on move. More puzzles showed suspended pawns delivering checkmate by promoting to any piece, minor or major.

The rule of promoting only to lost pieces presented other curiosities. Queens could be sacrificed and reincarnated in succession. There was also a downgrading effect on promotion itself: if only bishops were captured from the board, promotion was thus forced to a bishop. But confusion began when pawns on dark squares were promoting to light-squared bishops.

Both Del Rio and Theory of Chess author Peter Pratt supported the rule in the early 18th century, suggesting that players needed to manage exchanges with future promotion possibilities in mind. But the two differed when promotion led to having two bishops on the same color: Pratt allowed the promotion where del Rio prohibited, even if the situation meant leaving a pawn suspended.

The alternative idea was what would become our modern rules of promotion, and the idea of promoting only to lost pieces was soundly rejected by these authors. In the Art of Chess-play: A New Treatise on the Game of Chess, English author George Walker in 1841 argued that, under the lost-piece promotion rule, losing the ability to promote to a second queen – since the first queen was still on the board – was too big a penalty compared to the difficult task of promotion.

"The power granted by the law, of your having two Queens on the board at once should you push a Pawn to the eighth square, has been much cavilled at by various authors; but in my opinion presents by far the best means of meeting the difficulty, consequent upon the every-day occurrence of queening a Pawn before any piece is lost."

But the lost-piece promotion rule lingered for decades, and was still observed in parts of Italy and Germany through the rest of the 19th century. Howard Staunton was a huge champion of the modern rules during this time, repeatedly informing correspondents that a player may have two queens – once noting in exasperation how often he had to point this out. The modern promotion rule finally became standard at the end of the 19th century.

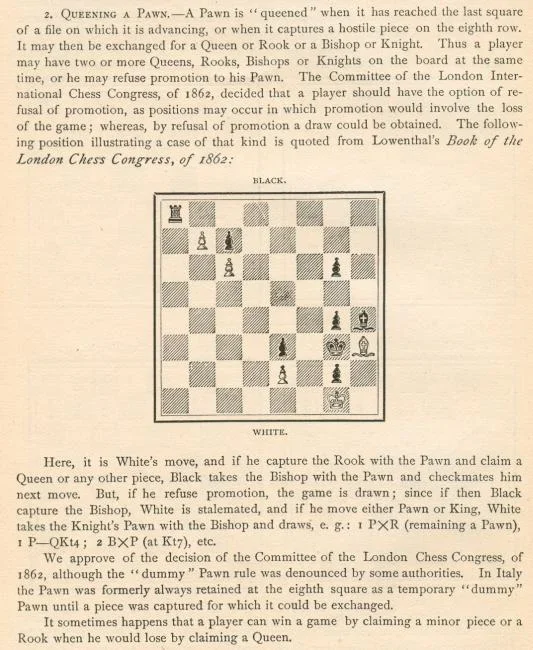

Discrepancies, of course, remained in the rules. In 1862, the British Chess Association created a rule that allowed pawns to stay permanently suspended on the last rank, a dummy piece with no possibility of future moves or promotion. The practical effect of this rule was virtually nil, and Staunton focused heavy criticism on the BCA code and its dummy pawn. Advocates published a simple composed position as justification, which showed a dummy pawn saving a draw by aiding self-stalemate.

But American chess composer Sam Loyd published a mate-in-three problem in 1898 that proved the opposite effect, showing White promoting to a dummy pawn – which controls no squares – and preventing Black from saving the draw by self-stalemate for two moves, then allowing checkmate on White's third move. Regardless, the BCA's dummy-pawn rule had no impact on either competition or composition before disappearing from future codes.

Issues even arose that concerned whether a pawn could promote to an opponent's piece! Despite any obviousness to the idea, early rules neglected to clarify this point and loopholes were left. Walker in 1841 described an important match where a player accidentally replaced his promoting pawn with his opponent's queen, and the opponent insisted that the accidental promotion stand! The ruling was referred to nearby players, whose opinions were divided since the published rules didn't specify color.

When I met the notorious IM Norman Whitaker, a young 80 years old in 1970, he told me that in his youth some still argued that a pawn could promote to the opposite color. The idea came up in compositions, mostly "trick" problems, such as one presented in the February 1906 issue of Lasker's Chess Magazine.

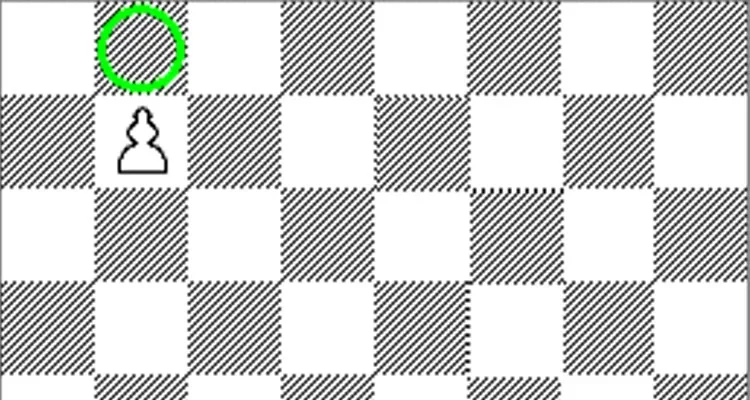

One lasting issue concerned how to represent a second queen or a third piece, and the earliest suggestion I found using an inverted rook for a second queen was in an encyclopedia of games in 1897 – which also suggested putting a ring around the pawn.

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (8)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)