The question of whether chess was invented or evolved from earlier games may never be settled. Part of the discussion is semantic, since evolution and invention are two sides of the same coin! Evolution is a series of new inventions that build upon or combine earlier designs. Inventions are steps in evolution.

Chess rules and customs, even today, are constantly evolving. Through research into old chess literature, I've made some original discoveries regarding how modern rules and customs have evolved to reach their current state. This series will explore some specific rule changes for chess that have evolved over the past few centuries.

Click below for earlier chapters of John McCrary's Evolution of Modern Chess Rules series:

EN PASSANT CAPTURES:

As early as 1200 A.D., pawns have been able to move forward two squares forward on their initial move. The point of contention was if a pawn could use this two-square move to bypass the control of an opposing pawn, and various local rules resulted over the centuries. Some regions simply did not allow the two-square move at all, if it meant passing an opposing pawn; others would not allow the move while defending a check.

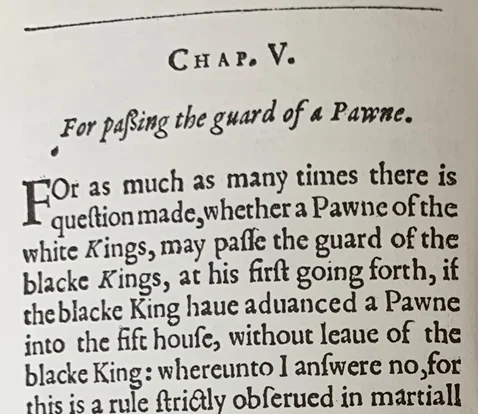

In his book The Famous Game of Chesse-Play in 1614, Arthur Saul wrote that a pawn had to have the "leave" of the enemy king to pass, without clarifying what was meant by such "leave.”

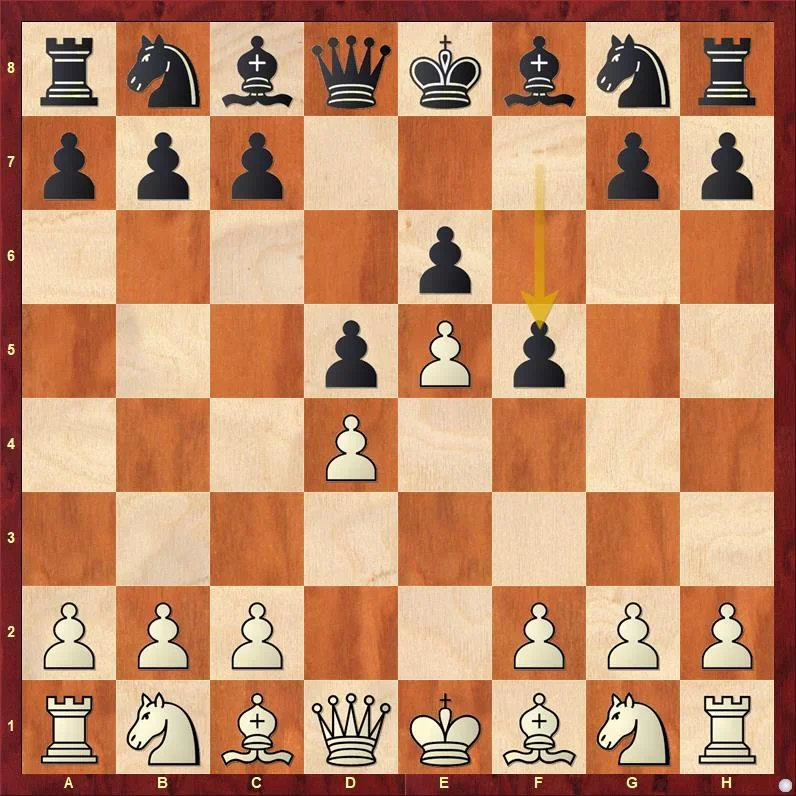

By the early 19th century, two variants existed that either allowed, or disallowed, the en passant capture. The move was present in England and its surrounding regions, while capturing en passant was not allowed in Italy and Germany. The rule difference had its effect on opening theory; for example, in Italy after 1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5 3. e5, Black could play ...f5 without the threat of immediate capture.

Capturing en passant brought with it some unique features. For starters, it's the only way a pawn can attack an opposing pawn, without having a reciprocating attack possible for that opposing pawn. Additionally, it's the only move possible for just one turn, after which it becomes impossible. Thus, some combinations that rely on an "in-between" move may not work when an en passant capture is involved. Lastly, en passant is the only move that can give double-check without the moving piece delivering one of the checks.

Before the modern rule became universal in the mid-1800s, debates occurred about its proper form in those regions where en passant captures were allowed. Some questioned why it applied only to pawns: After all, pawns pass pieces, and pieces pass each other with impunity -- so why couldn't pawns? Curiously, some printed rules failed to specify that it was limited to the immediate reply, though the idea was expressed clearly by some, showing it was presumably understood. But only in recent decades the rule was clarified to state that, in a triple-occurrence draw claim, a position is not a repetition of an earlier position, if an en passant capture was possible in that first position.

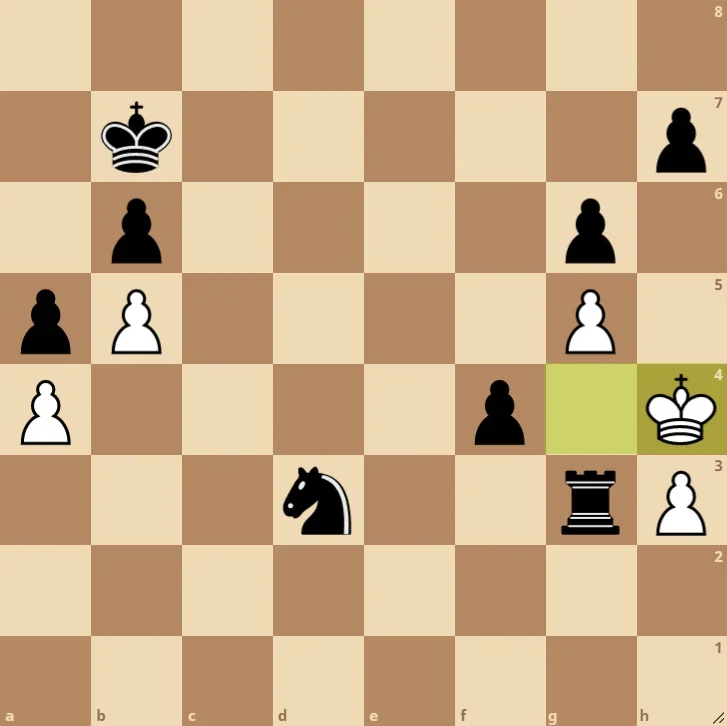

There was also much debate regarding whether en passant capture was a "privilege" and thus could be refused, if it was the only legal move to prevent a self-stalemate. That debate would seem to be academic, as such a position would be of rare occurrence, though composed problems and studies presented these issues with more clarity.

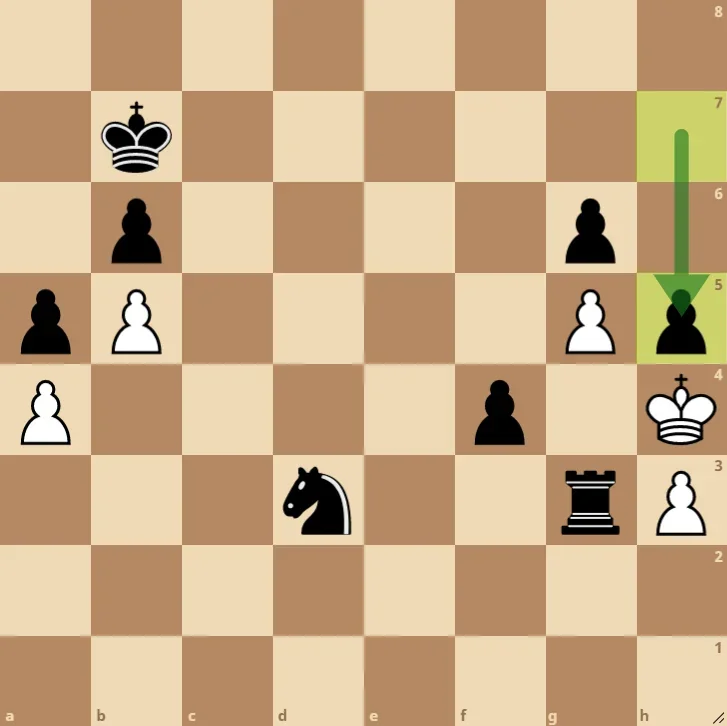

By definition, a composed position has no preceding moves, so having an en passant capture as the first move of a solution became an issue, when it couldn't be known if the preceding move was a double-jump of a pawn. Some problem-composing contests simply prohibited having an en passant as the key move. One composing contest in 1883 allowed an en passant capture as the key move, but only if the position could not have been reached by any hypothetical game in which the capture was illegal. The contest rules stated This device, however, shall under no circumstances enhance the value of a problem.

Today’s modern convention of composed positions, however, does allow an en passant capture as the key move – only if the position could not have been legally reached by a move other than the double-jump that made the en passant legal. If the position could have been reached by another move, the key cannot be an en passant capture.

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (2)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)