The question of whether chess was invented or evolved from earlier games may never be settled. Part of the discussion is semantic, since evolution and invention are two sides of the same coin! Evolution is a series of new inventions that build upon or combine earlier designs. Inventions are steps in evolution.

Chess rules and customs, even today, are constantly evolving. Through research into old chess literature, I've made some original discoveries regarding how modern rules and customs have evolved to reach their current state. This series will explore some specific rule changes for chess that have evolved over the past few centuries.

Click below for earlier chapters of John McCrary's Evolution of Modern Chess Rules series:

THE FIFTY-MOVE DRAW:

The 50-move draw rule, which today states that a draw can be claimed if no capture is made and no pawn is moved for 50 consecutive moves, took centuries to reach its modern definition.

In early chess treatises, there were rules that addressed the problem of players who reached a basic, theoretically won endgame but lacked the skill to achieve a mate. A king-and-two-bishops versus a king, or perhaps a king-and-queen versus a king-and-rook, even the basic king-and-queen versus a king poses problems among beginners. The player with the won endgame might make an interminable number of moves without progress, but also without consenting to a draw. Early rules acknowledged a limit to the number of moves allowed to reach mate in basic endgames, though differed on that number, ranging from 24 moves up to 50 and more.

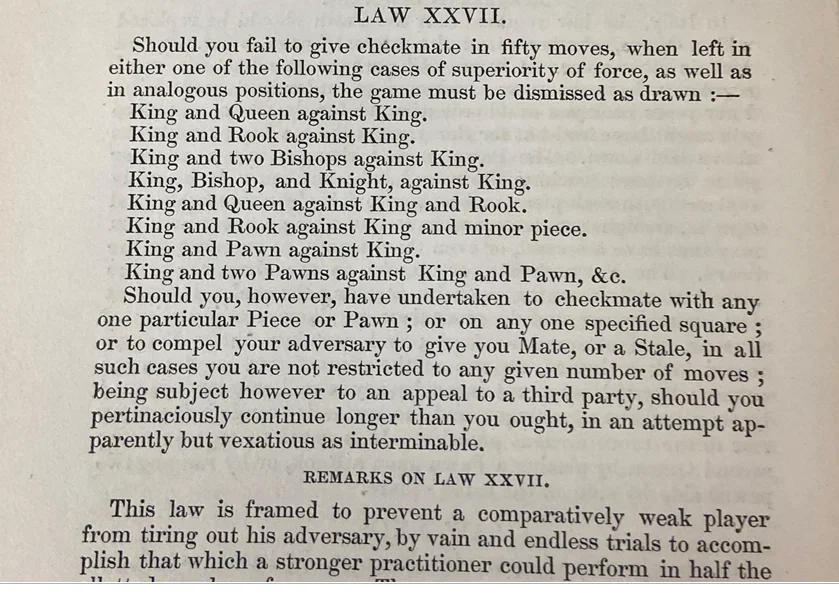

Agreed upon around the mid-1800s was the enforcement of a 50-move limit when it was unclear that a player could reach mate. But difficult was defining those endgames in which that limit was appropriate, given the vast possibilities of situations. In his book The Chess Player in 1841, George Walker listed as one of the ways a game might be drawn:

"By the stronger party possessing the mating power, but not knowing properly how to direct its application. Thus the King with two Bishops, against King alone, has force sufficient to mate with; but if he cannot give mate in fifty moves (double moves) according to the law, his adversary is justified in claiming a draw. So again, King and Queen against King and Rook have the mating power, but the superior force must not vex his adversary by persevering too long in attempting that which he is evidently too unskillful to accomplish."

Walker focused much on pawnless endgames in which one side had an advantage that was theoretically sufficient to force mate, though he added more grounds to begin a 50-move count with "perpetual checks, or reiterated attacks involving the same forced moves in answer" -- that is, a king who was being chased around the board by a player who didn't know how to achieve mate.

Also in 1841, Howard Staunton published the following law from the code issued by the London Chess Club:

"If a player remain at the end of the game, with a Rook and Bishop against a Rook; with both Bishops only; with Knight and Bishop only; he must checkmate his adversary in fifty moves on each side at most, or the game will be considered as drawn; the fifty moves commence from the time the adversary gives notice that he will count them. The law holds good for all other checkmates of pieces only, such as Queen, or Rook only, Queen against a Rook."

This London Club code required a player to give prior notice that he was counting the 50 moves, and also implied, by using the words "of pieces only," that only pawnless positions with some material superiority were appropriate for such a count to be imposed.

But players in that time found the criteria cited by Walker and Staunton too limiting. Arguments were made for the 50-move rule to apply to more situations where a player didn't have the skill to win a won endgame, or played endlessly without making progress in a drawn endgame. But there was no clearly worded definition of when a 50-move limit might be appropriately demanded.

Some suggested that bystanders should rule if a position was appropriate for a 50-move count, since defining the kind of position was too vague in the general laws – but what guidelines were the bystanders to use? Staunton in 1847 said: "The law on the subject of fifty moves at the end of the game is too indefinite".

The 50-move rule encountered other issues and much more debate throughout the 1800s. There were arguments that supported changing it to 60 moves, and others to abolish the rule altogether. Some began to question whether the count be started anew with each capture, since captures changed the obvious nature of the endgame. And surprisingly, pawn moves were not often addressed in these early debates, despite their ability to alter the nature of the endgame, especially when involving promotion.

Additionally, the requirement that one player demand the 50-move count in advance created a unilateral situation that could cause its own problems. Suppose the player who demanded the count changed his mind because he saw a way to win during or after the 50 moves? Could his opponent hold him to his prior demand for a count and insist on the draw?

The 5th American Chess Congress, held at the Manhattan Chess Club in New York City in 1880, issued a code that attempted to address these various issues with the following law:

"If, at any period during a game, either player persist in repeating a particular check, or series of checks, or persist in repeating any particular line of play which does not advance the game, or if a 'game-ending' be of such doubtful character as to its being a win or a draw, or if a win be possible, but the skill to force the game questionable, then either player may demand judgement of the Umpire as to its being a proper game to be determined as drawn at the end of fifty additional moves, on each side; or the question: 'Is, or is not the game a draw?' may be, by mutual consent of the players, submitted to the Umpire at any time. The decision of the Umpire, in either case, to be final. And whenever fifty moves are demanded and accorded, the party demanding it may, when the fifty moves have been made, claim the right to go on with the game, and thereupon the other party may claim the fifty-move rule, at the end of which, unless mate be effected, the game shall be declared a draw."

This elaborately worded law adopted at the 5th American Chess Congress was used in the following Congress in 1889, where an important game proved there was still ambiguity. An endgame was reached in a game between Russian Mikhail Chigorin and American Max Judd, with Judd calling on the law’s wording “if a game-ending be of such doubtful character as to its being a win or a draw.” The American demanded a 50-move count, which was authorized by the umpire to begin.

But during the next 50 moves, the nature of the endgame experienced a significant shift, with both sides queening a pawn and several more pawns exchanged -- though Judd claimed the 50-move draw anyway, noting that the law made no reference to exchanges by pawns or their promotions. Chigorin insisted the game continue, since those same promotions and exchanges had changed the position significantly. But Judd maintained that his choice of moves had been influenced by his belief that an automatic draw would be given if mate had not been delivered in 50 moves.

Both Chigorin and Judd posed reasonable viewpoints given the ambiguities in the law, though the umpire directed the game to continue. In protest, Judd refused to finish the game, and Chigorin was awarded a forfeit win by the tournament jury -- which proved major significance to the event, where Chigorin finished in a tie for first place. Using the game as an example, the Congress players later unanimously approved a change in the law, allowing the umpire to determine if a game was a draw after the 50-move limit had been reached.

The Judd-Chigorin dispute would not have occurred had the 6th American Chess Congress instead used the "Revised International Chess Code," which was published for the London 1883 international tournament. That code stated:

"A player may at any time call upon his adversary to mate him within fifty moves (move and reply being counted as one). If by the expiration of such fifty moves no piece or pawn has been captured, nor Pawn moved, nor mate given, a draw can then be obtained."

This rule is closer to the modern rule, in that it (finally!) made no attempt to define which kinds of endgames the rule should be applied, and ended any 50-move count with a capture or pawn move. The law remained unclear, however, on which player could then claim the draw -- if the requesting player perhaps changed his mind and withdrawn his demand during the 50 moves. Furthermore, it required that a player must demand the 50-move count before it began, while today’s modern rule allows retrospective counting.

Despite being close, this "Revised International Code" did not receive immediate widespread acceptance, published only for "the consideration of chess players and especially of the managers of future international chess tournaments."

The requirement that a count be demanded in advance was removed in the 1897 American Chess Code, thus clarifying that either player could claim the draw after 50 moves. It allowed retrospective counting, with each capture restarting any 50-move sequence, and made no attempt to define the kinds of positions to which it might apply. But still the code made no reference to the influence of pawns, something that did not show up until the Cambridge Springs International Chess Tournament in 1904, which required a count to start anew after any capture or pawn move.

Finally, in 1918, the International Chess Code was published with today’s modern understanding of the 50-move draw rule: The count was not required to be demanded in advance, and it would restart after captures and pawn moves. Even still, the FIDE rules continued to evolve as recently as 1931, attempting to clarify that a player could demand a 50-move count, though could also claim the draw even if a count was not previously demanded. This redundancy was later removed.

Even today, the modern rule still is subject to question, having seen certain kinds of endgames that need more than 50 moves to be won by force, without capture or pawn moves. Furthermore, the 50-move rule still does not prevent players from dragging out hopeless endgames, when occasional captures or pawn moves extend them.

The 50-move draw rule may have more evolution yet.

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (13)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)