The question of whether chess was invented or evolved from earlier games may never be settled. Part of the discussion is semantic, since evolution and invention are two sides of the same coin! Evolution is a series of new inventions that build upon or combine earlier designs. Inventions are steps in evolution.

Chess rules and customs, even today, are constantly evolving. Through research into old chess literature, I've made some original discoveries regarding how modern rules and customs have evolved to reach their current state. This series will explore some specific rule changes for chess that have evolved over the past few centuries.

Click below for earlier chapters of John McCrary's Evolution of Modern Chess Rules series:

Part Eight: Triple-Occurrence Draw

Enter the Queen and Bishop:

Questions are invariably asked on how the queen became chess’ strongest warrior, and how bishops, in modern times considered officers of peace, became soldiers in the chess army. The history of Western society suggests some answers.

The queen was a medieval addition to the chess board and had entered the game as early as 997, replacing a piece that represented a king’s minister. Players in those times may have been more accustomed to the idea of a fighting queen, as various lands held several strong queens who sometimes managed troops and military matters.

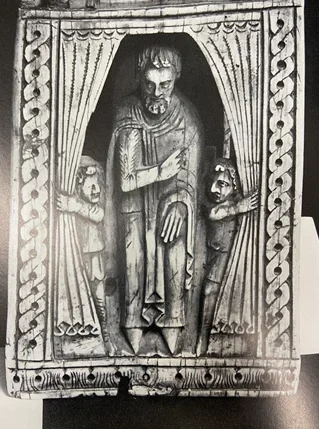

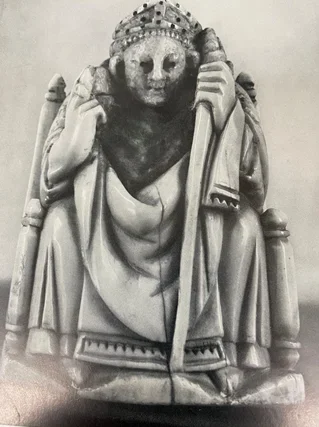

The 2015 book Ivory Vikings: The Mystery of the Most Famous Chessmen in the World and the Woman Who Made Them is an intriguing treatment on the potential origins of the Isle of Lewis chessmen, and discusses various historical factors surrounding the famous 12th century chess set. The author Nancy Marie Brown notes several 10th-century queens who may have inspired the appearance of a fighting queen on the chess board, stating:

"Medieval queens were expected to wage war, at least by proxy. Empresses, like [the Holy Roman Empire’s] Theophanu, accompanied their men to the battlefield."

But the first chess queens, like the minister piece that preceded them, were limited to moving only diagonally and only one square at a time. This limitation to reach just 32 squares and slowly, the queen piece was weaker than kings, knights, and rooks – all of which had the same moves and abilities as they do today. The sudden increase in the queen's powers did not occur for centuries after the piece had appeared in chess sets.

Bishops had entered chess by the mid-1200s, replacing an earlier piece that had represented an elephant. The animal was not well-known in the Western world at that time, and the elephant piece was phased out and replaced by a more-familiar figure. And while the idea of a warrior bishop was not universal, having a bishop in the chess army might have seemed more natural in medieval times than it does in modern consideration. In feudal society, bishops often had political power and were part of the medieval nobility.

In his book The Age of Faith, Will Durant provides the following descriptions of the feudal church:

“So enmeshed in the feudal web, the Church found herself a political, economic, and military, as well as a religious institution...with feudal rights and obligations … Archbishops, bishops, and abbots received investiture from the king, pledged their fealty to him like other feudatories ... and took on the feudal tasks of military service … Bishops or abbots accoutered with armor and lance became a frequent sight in Germany and France. Richard of Cornwell, in 1257, mourned that England had no such ‘warlike and mettlesome bishops.’”

Ironically, despite its lack of such armored bishops, England established the bishop on the board, while France and Germany chose other terminology: respectively, the two regions preferred "fool" and "courier." Despite the disparate nomenclature, however, the bishop's evolution was the same, retaining the weak powers of its preceding elephant piece. Movement was limited to only two squares diagonally - no more, no less - meaning each bishop could reach only 8 of the 64 squares. It's value was roughly equivalent to a pawn.

The queen and bishop gained their stronger powers in the late 1400s, suddenly. On the how and why behind these changes is a recently published theory, and my own.

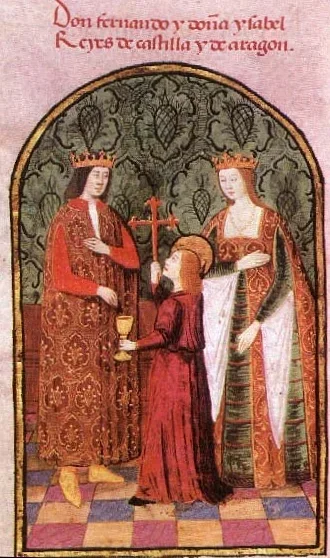

The recent theory suggests that the increase in the queen's power was inspired by Queen Isabella of Castile, a powerful monarch whose reign was roughly contemporary with the increase in power of the chess queen. Advocates of this theory, however, still need to explain the simultaneous increase in the bishop's powers, which would have had no connection to Isabella.

Some supporters of the Queen Isabella theory have argued that the bishop's movement might have already been increased, carried over from a 12th century variant called courier chess -- though there is no evidence that these long-range powers had been used for, much less replaced, the bishop's otherwise limited movement in the real game.

My theory is that these powers were introduced as a variant of chess, one that intended to be a faster version of medieval chess, though still able to be played with the existing boards and sets. In Medieval chess, only rooks, which had been chariots in the early game, could move rapidly around the board; the other pieces were limited to short-stepping moves. Using the long-range abilities of the rook as a model, the faster-chess variant’s simple idea was allowing a piece that moves like the rook but along diagonal lines. Carrying the idea one step further was allowing a piece to move freely along all lines.

And how to adapt these ideas into the game without impacting existing sets should seem relatively obvious: simply bestow these new upgrades on the current weakest pieces, the queen and the bishop. Enhancing the two bishops with the new long-range diagonal movement worked great, not only keeping their spots in the opening position, but now able to hit all 64 squares as a pair. And since the queen was a solitary piece – and a royal one – rewarding it with the most-powerful skillset worked out naturally.

One awkward issue within my theory of the 15th century variant remains without an obvious explanation: All these ideas seem applicable to the times and sets that existed, except the king, who needed to maintain his limited movement to allow checkmate, would now be less powerful than the new queen. Perhaps the inventor of this variant was a woman who thought this had worked out quite well.

As long as the queen's increase in powers is assumed to have been simultaneous with those of the bishop, my hypothesis seems to better-explain the sudden increase in both pieces than the Isabella hypothesis. More common sense that flows from a general idea of speeding up a slow game and adding powers that were complements to piece movements that already existed in the game. Then the very practical idea of introducing these rules to existing sets, thus avoiding any need for newly designed pieces or enlarged boards, simply by replacing the weakest pieces in the old game. Being able to use the old equipment would no doubt serve as encouragement to try the new moves.

Furthermore, it seems unlikely to me that introducing a major change in any game, which effectively creates a very new game, would be done just to honor a monarch. Also unlikely is this radically changed, new game driving out the old game into universal extinction across many nations, including nations where this monarch wasn’t popular.

To me it seems far more likely that major changes in the game were motivated solely by a desire to create a superior practical game. After all, the 15th century, which also saw the invention of the printing press and the voyages of Columbus, was a time in which old ideas and customs were being challenged, and new ideas being tried in many areas.

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (6)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)