Editor's note: this story first appeared in the November 2025 issue of Chess Life magazine. Consider becoming a US Chess member for more content like this — access to digital editions of both Chess Life and Chess Life Kids is a member benefit, and you can receive print editions of both magazines for a small add-on fee.

We also provide a pdf version of the article for those interested in reading it in full layout.

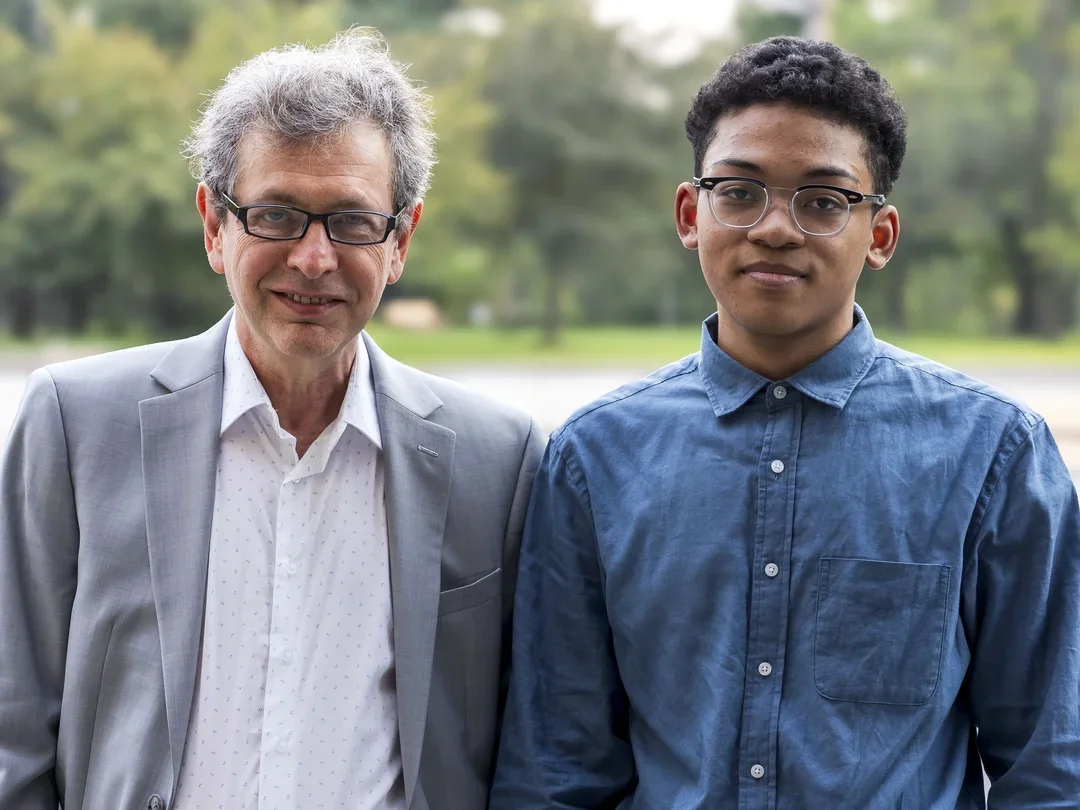

Brewington Hardaway breaks through to the GM title.

Imagine waiting 25 years to see a dream come true.

When I became the first African-American in history to attain the GM title, in 1999, the expectation was that there would be many more to quickly follow. It still boggles the mind that it took this long before another Black person here in the United States would replicate the feat. However, it finally came to pass last year in the form of Brewington Hardaway, a 15-year-old prodigy from the Bronx who never would have taken up chess in the first place if not for a funny twist of fate.

Brewington, now 16, is the youngest in a family of four. As luck would have it, his mother, Ikuko, enrolled one of his sisters for chess club when he was 5. Brew’s parents decided that it would be easier to leave him in the chess club with his sister than take him home and then have to return to pick her up.

“The story goes that my sister Noni signed up for chess, but didn’t really like it,” Brew remembered during our Zoom call. “But the cost was $150, and my mom said that she had already spent the money, so my sister had to do it. If Noni had quit chess, I don’t know if I would have ever played chess. Probably not.”

While Noni would soon come to enjoy chess, eventually reaching the top 20 in the country for her age group among girls, the effect chess was having on her baby brother would lead to the discovery of a world-class talent.

“I just sat over in a corner of the room drawing and doing homework,” Brew recalls. “Every so often, I would look up to watch the big screen with all the puzzles and see the kids playing, and I started to gain interest. I eventually asked how this game works, and ever since, I’ve been hooked.”

Within about a month, the coach of the club, Chris Johnson, began to understand that the young boy wasn’t an average kid.

“As a kindergartner, he beat everyone in the club, including the fourth graders,” said Coach Johnson, an expert who now runs a citywide program in NYC called Project Pawn. “By the time he got to first grade, he started beating a few of the coaches too. He could barely tie his shoelaces!”

Johnson recalled the moment he knew Brewington was special: “I showed him a bunch of lines in the Sicilian, and then months later he still remembered everything. I never had to show him the same thing twice.” At age 5, Brewington won the New York K-1 championship, and Johnson remembers that while “everyone else was celebrating, he was still going over the games he had just played, still trying to improve.”

‘She thought I was lying’

Brew had a massive breakthrough just two years later when, at just 7 years old and rated 1537, he defeated IM Jay Bonin, a New York City legend.

“I played my only opening then — the Benko,” Brewington recalls. (Johnson says that, coincidentally, they had just gone over the line a week before.) “I remember I hit Jay with a nice tactic and won two pieces, so he resigned. When I told my mom I’d won, she thought I was lying.”

Coach Johnson remembers seeing a photo of the winning scoresheet that Ikuko had texted him: “I was shocked that he had beaten someone so strong so early on in his development, but I wasn’t really surprised, if that makes sense. This is a kid who used to fall asleep at night at his laptop while going over chess. I told his mom that one day soon he would be a GM.”

(In a curious twist of fate, Coach Johnson’s very first coaches were Kasaun Henry, Charu Robinson, and Daniel Gray, who were members of the Raging Rooks, a team I coached to a national championship title back in 1991).

One would have expected such a victory to motivate the youngster to work extremely hard to get even better. However, it was a few more years before he would take chess seriously. “Honestly, back then, I didn’t even study chess,” Brewington says with a smirk. “I just played for fun. I barely did anything outside of the school chess club — no openings, only puzzles. … I didn’t even know what the IM title meant or even what a FIDE rating was. … I just played chess because I enjoyed it.”

Three years later, at age 10 and still not studying consistently, Brewington gained the title of national master, defeating Bonin once again as well as other highly rated players along the way. Even these results hadn’t yet been enough to spark the singular focus a young talent needs to get to the highest levels. That would come from another twist of fate, when the COVID-19 pandemic forced everyone into lockdown, prompting him to pursue the game full-blast.

That was where he realized “I just loved to play. Whenever I saw a nice tactic, it made me happy. Something about all the different possibilities, cool tricks, positional ideas — it always made it interesting for sure.”

Setbacks and stepping up

Two years of secluded study plus work with a new coach, GM Gregory Kaidanov, saw a period of accelerated growth. Now he was tearing up the New York scene, and it was time to go outside of familiar territory to tournaments around the country.

The next big breakthrough came at what many would consider a moment of personal failure: In the last round of the 2022 SPICE Cup, Brewington needed only a draw to secure an IM norm, he made a crucial mistake that cost him the game. However, instead of hanging his head in defeat, he was able to reframe it as a positive outcome.

“Losing the game was tough for sure,” he recalls. “I was not really happy, obviously. But at that point I realized that norms were possible. … I hadn’t come close before. To get close like that was definitely motivational.”

That mindset helped catapult him at the beginning of 2023 when he scored two IM norms in back-to-back tournaments in New York. He also came agonizingly close to the 2400 rating required to secure the title by reaching a live rating of 2399.4! The third norm followed in July of that year at the World Open, but it would be November before the elusive 2400 rating would be finally achieved — at the U.S. Masters, in Charlotte, he gained 62 rating points, the IM title, and his first GM norm in one fell swoop.

With his confidence soaring, it now seemed like the wind was at his back. 2024 kicked off with a bang when, in his very first tournament of the year, he sprinted to a 5-0 start and coasted with four draws to finish with a 2668 performance rating, a half-point over the GM norm. However, the next several months saw only decent results, with a modest rating boost, and then a depressing setback at the U.S. Junior in St. Louis.

“I had three completely winning positions that ended in a loss and two draws,” he says. “That was really tough for me. If I had won all those games I would have tied for first. I could see I had the middlegame strengths to make the GM title, but my conversion and focus needed to improve. In the critical moments, in time pressure; that’s when I stumbled. I realized that I had to try to not overthink things, to manage my time better and have more self-confidence.”

Those realizations stayed with him as he took aim at a summer tournament in Barcelona, Spain. After a modest start, he picked up steam and then found himself face to face with one more major obstacle to clear the last hurdle.

“It’s funny because in the second-to-last round, I thought I had to make a draw against a random 2330 to get my final norm,” he recalls. Instead, he ended up with Black against German GM Alexander Donchenko, who had a peak rating of 2684. “But I told myself that if I could draw a player of that level with Black, then I really deserve the title. I ended up playing a 99% accuracy game and got the draw.”

A little more than two months later, Brewington eclipsed the 2500 mark at the New York Fall GM Invitational, finishing with an undefeated 6 out of 9. In doing so, he cemented his place in history as the second (and by far the youngest) African American to secure the GM title. It was a relief to him and pure joy to those of us who had followed his quest. Though the journey seemed a bit drawn out, he actually secured his three IM and three GM norms in just 21 months.

Brewington credits Kaidanov for helping him navigate the twists and turns of the journey. (Coincidentally, Kaidanov was my coach when I attained the GM title as well.) As Brew put it, “The GM title was really all thanks to him. During all these ups and downs, he was really supportive. He let me know that bad things happen to everyone. He let me know I had all the tools I needed to become a top player. That was really good to hear.”

As for what it means to be an African American in a sport where there is so little representation, Brew, as he often does, put on a positive spin.

“I just see it as an opportunity to inspire kids from a similar background. There are not many others besides my good friend, Tani [IM Tani Adewumi]. I think there’s a lot of potential out there; we just need kids to have motivation and inspiration to reach their potential.”

What’s next?

With so much talent and a fairly rapid rise, he speaks about the future with a blend of high aspirations and pragmatic realism. His next stop: Get to 2600 in the next two years, before high school is over.

“I feel like I still have a lot to improve, of course. I don’t think my rating shows the work I’ve been putting in. … I think over time if I keep working as I am, the rating will start to show. I’m just gonna keep training, then the results will come. I’m not too worried about it.”

As for one day becoming the World Champion, he simply replied: “Isn’t that everyone’s dream?”

Nowadays, he spends at least three to four hours a day working on openings, calculation training, and a bit of the endgame, while additionally using blitz to practice the opening lines he’s been learning. He balks at the idea of studying all day long like some of his peers.

“I personally can’t see myself focusing for eight to 10 hours on chess. I like to do other things like going to the gym to be in shape and watching NBA basketball. That’s also important for tournaments. There’s other things in life to do other than chess. I try to be well-balanced, but when I work on chess, I try to be really focused and maximize the time I have.”

Four Pivotal Games (annotated by GM Brewington Hardaway)

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (13)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)