Gender and the President's Cup: A Statistical Analysis

Introduction by Dr. Alexey Root, WIM: Since 2001, the President’s Cup has been the national championship of college chess in the United States. The top four U.S. schools from the previous Pan-American Intercollegiate Team Chess Championship (Pan-Am) meet every spring, usually on the same weekend as college basketball’s Final Four.

While GM Susan Polgar calls the teams she coached at Texas Tech University and at Webster University “men’s” teams, that “men’s” terminology is not true for the President’s Cup in general. Eighteen unique women have been on President’s Cup teams’ rosters, with several women playing multiple games in multiple years.

For round-by-round results and chess games, see this President’s Cup website developed by Graeme Cree with my assistance. I am also writing a book about the President’s Cup, to be published by McFarland. See my note at the end of the article for how you can help contribute to this book.

In this article, Evie Laskaris, Class of 2027 at St. John's School in Houston, analyzes statistics from the President’s Cup website.

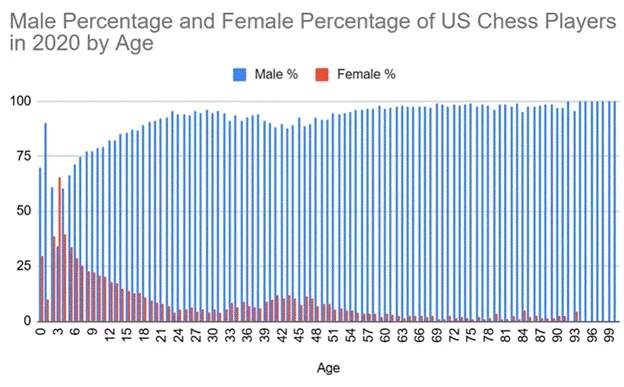

Chess is a competitive and strategic board game that is dominated by male players. As of February 23, 2021, among recent US Chess members (expiration dates 12/31/2020 or later), 12.4% of US Chess members were coded as female while 85.4% were male. And this percentage was higher than what existed in the 20th century, when fewer than 5% of members were girls and women. This gender gap is evident at every level of chess playing, from beginner to master, and it only grows as players age. By age six, according to the above report, over 70% of members were male, but, by age 18, that percentage was up to 89%

It is therefore no surprise that the majority of US Chess competitions have almost entirely male participants. One example is the President’s Cup, an annual chess tournament featuring the top four U.S. college teams. As of 2025, 237 unique men and just 18 unique women have been on teams’ rosters for the President’s Cup (with some competing more than once).

Why is there such a massive gender gap in the chess world that has persisted for many years? And why does there appear to be significantly more men than women at the highest level of the game? Where are the women in the chess world?

What is the President’s Cup?

The President’s Cup crowns the top collegiate chess team in the United States. It was established in 2001 and has been held annually except in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The President’s Cup is a three-round round-robin tournament, with each team usually consisting of four players and up to two alternates (one exception was in 2021, where the tournament was hosted online and consisted of six rounds).

In 2002 and 2009, when teams tied for first place, both the President’s Cup trophy and the champion’s title were awarded via tiebreaks. But in more recent years, the rules allow for co-champions, with tiebreaks determining the recipient of the physical President’s Cup trophy. For example, in 2025, Webster and UTRGV were declared as co-champions and Webster took home the President’s Cup.

Gender Differences in the President’s Cup

This report summarizes my analysis on gender differences, which can be reviewed in full here. Note that, in this analysis, there are multiple tabs, offering different groupings of the data and additional analysis. There are statistics for every player: their name, how many times they were marked as a player, how many times they were marked as an alternate, their gender, and their school(s) that they competed for.

Then, the years from 2001 and 2025 (excluding 2020, when the event wasn’t held) show the participation status of each player. If the tab is bright green, then the player was marked as a player and played. If the tab is dark green, then the player was marked as a player but didn’t play. If the tab is bright yellow, then the player was marked as an alternate who played. If the tab is dark yellow, then the player was marked as an alternate and didn’t play any games. The third tab, “Women’s Stats,” shows data analysis specifically highlighting the women in the President’s Cup.

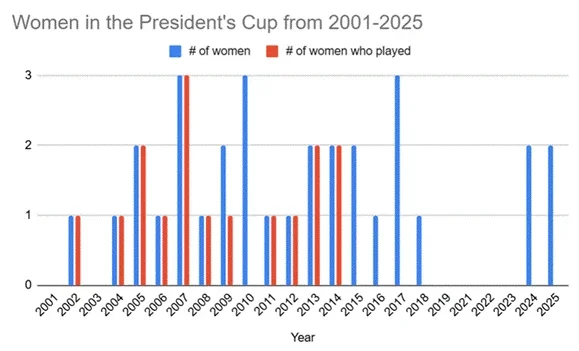

As previously stated, only 18 unique women have been on teams at the President’s Cup, a stark contrast to the 237 men, and this is further compounded by the fact that there are slightly more, on average, women than men in colleges. In addition, only half of the women on the President Cup’s teams actually played at least one game.

There have been no more than three women who played in a single President’s Cup, which occurred in 2007 (on average, there are around 18 total players per year). After 2007, women’s representation in the President’s Cup declined. From 2015 to 2025, no woman has ever played in the President’s Cup. The last time a woman played a game in a President’s cup was 2014, when both IM Nazi Paikidze and WGM Sabina Foisor played on University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC)'s team. Since then, any women on team rosters showed up as alternates who didn’t play, if there were any alternates that year.

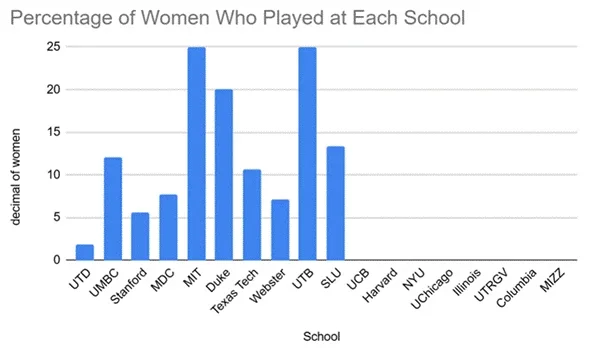

Women have not been in the majority on any single college team, with MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) and UTB (University of Texas at Brownsville) featuring the highest percentage of women on their teams at 25 percent. Webster University also featured their first two women on their President’s Cup team in 2025, a promising trend for future female participation in the tournament. Nevertheless, around 44 percent of colleges that have competed in the President’s Cup have never included a woman on their team.

Yet one female player, WGM Katerina Rohonyan, was critical to UMBC winning the President’s Cup in 2005 and 2006. Rohonyan won two games (out of the two games that she played) in 2005 and two games (out of the three games that she played) in 2006. Although the President’s Cup is a competition for teams, not individuals, Katerina Rohonyan also placed high individually compared to her teammates and players competing for other teams. The cross tables show her as tied for third through fifth places in 2005, tied for third through sixth places in 2006, and third place in 2008. In fact, UMBC qualified for fifteen President's Cups in a row and won six of them, and four of these victories included a woman on the team.

Teams with female players also won in 2009, 2010, and 2025; however, the females on those teams in those years did not play any games. It is not uncommon for players designated as alternates to not play any games. A full table of all women to play on President's Cup team, by year, is here.

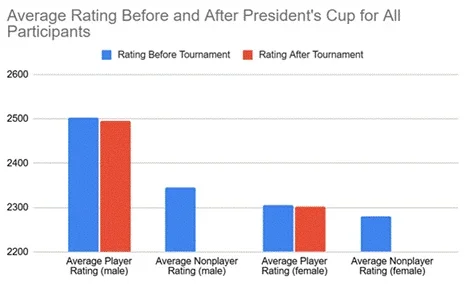

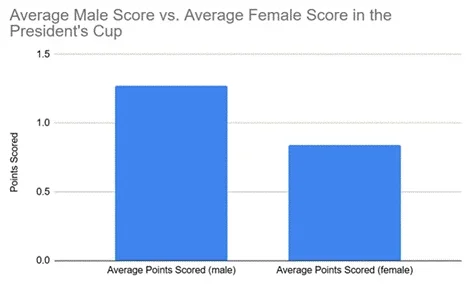

The average male player’s rating in the President’s Cup upon entering the competition was around 2502, while the average female player’s rating in the President’s Cup upon entry was around 2305. (The average nonplaying male in the President’s Cup had a rating around 2345, while the average nonplaying female had a rating around 2281.) Furthermore, male players in the President’s Cup scored almost half a point higher on average than female players.

Why are Women Underrepresented in the President’s Cup?

A May 2025 working paper by Kisida, Pepper, Podgursky, and Wickman, proposes that the primary reason for the rating gap between male and female chess players rated by US Chess is rooted in differences at entry; significantly more males begin playing chess than females. This initial disparity persists over time and becomes especially pronounced at the highest levels of competition.

The graph is based on a 2020 internal report linked here.

The 2020 internal report on US Chess membership by sex and age revealed that the gender gap in participation increases with age. The difference in the number of male and female players becomes pronounced as early as age 6. Among players aged 18–24, approximately 92.3% are male and 7.7% are female, similar to the percentage of women (7.05%) who have been on teams for the President’s Cup since its establishment. This information demonstrates that while more women may be playing chess competitively in recent years, the number of college-aged women who play chess competitively remains disproportionately low.

The disparity in the ratings difference can be attributed to the significant difference between the number of men and women who play chess competitively. The rating distributions for all female and male US Chess members are similar in shape. However, because significantly more men than women compete in chess, more men are represented at every level of chess-playing, including mastery. Therefore, the highest male ratings would, on average, exceed the highest female ratings, leading to male dominance in elite chess championships such as the President’s Cup.

We see that there are fewer top-ranked female chess players when looking at the data. This is not because girls lack talent. Research from the Royal Society and Professor Wei Ji Ma shows that when fewer girls enter the chess world, fewer reach elite levels. This argument has also been made by Bilalić et al. in a 2009 paper that argued that the gender gap in top-level chess performance is largely explained by participation rates, not innate ability. It shows that when fewer women enter chess, fewer will reach elite levels, even if they have the same ability as men.

In this ChessBase article by Dr. Wei Ji Ma, he argues that the rating gap at the top is due to ample size differences, not from ability differences. Ma explains that unequal participation alone can produce significant gaps at the top — even when abilities are identical.

Sexism in Chess

If rating differences are rooted in the number of males and females who begin playing chess, then why aren’t more females starting to play chess? While there are multiple factors contributing to this phenomenon, one likely contributor is sexism that discourages women from playing chess at every level. Some chess grandmasters have even stated that men have superior innate chess abilities to women, even though there is no evidence that women are biologically inferior at playing chess. The same article mentions that women in traditionally male-dominated roles are often frowned upon.

Sexism appears not only in chess but in any traditionally male-dominated roles. A 2017 study found that 6-year-old American girls are less likely to associate their own gender with ideas of brilliance or exceptional, innate genius. Other research has found that fields associated with this sort of brilliance tend to be some of the most male-dominated academic disciplines. While not an academic discipline, chess is a field long associated with prodigies, innate talent, and individual geniuses, so it would follow that young girls who are beginning to internalize these ideas of brilliance as male-coded would not see themselves as capable of success in chess and might look to other activities.

These pieces of psychological information reveal why the entry gap for men versus women is so profound in chess. Perceptions and established cultures are time-consuming to break. Unless there is strong motivation and external help to do so, it is far easier for girls to simply abandon chess, or to not engage in the game at all.

Future of Women in Chess

Increasing female representation in chess is essential for eliminating harmful general stereotypes that certain mental skills are determined by gender. Furthermore, inviting more women to play chess is likely to allow for a more accurate representation of female talent in chess, decreasing the rating gap and seeing more women at the professional level.

More women are gradually entering the chess world, with female US Chess membership growing from less than 5% in 2000 to over 12% in 2020. US Chess also has a women’s chess initiative, which is linked here. Increasing awareness of female capabilities in chess allows for greater female recruitment and thus more advanced female chess players and more female players competing in adulthood.

Conclusion

The President’s Cup is one of the most elite US Chess competitions for young adults. Historically, the President’s Cup has had significantly fewer women than men and, on average, men outperform the women and have significantly higher ratings. However, there is no evidence that women are biologically worse than men at playing chess than men; rather, women are underrepresented and discouraged in the chess world. The massive gender gap causes men to dominate professional chess and elite championships like the President’s Cup. However, more women have taken up chess in recent years and thus more women are entering the advanced levels of chess. Increased female representation in chess can reveal that women are just as capable as men in the chess world, which can also contribute towards the continuous advancement of women's participation in not only chess but also other male-dominated subjects.

About the author

Evie Laskaris is a junior at St. John's School in Houston. She is the founder of CheckmateFORKids.org, an organization she started in 2020 to teach chess to children, particularly in underserved communities. Passionate about equity, Evie is committed to motivating young girls to play chess and help close the gender gap. Beyond the board, she enjoys math, coding, playing the viola in her school orchestra, and adores spending time with her poodle, Olympia.

Editor’s Postscript

When reviewing this article, I (JJ Lang) was curious about the author’s observation that the participation of women in the President’s Cup has declined since 2007, with no woman playing a game in the Cup since 2014. My hypothesis for why this was the case was that more college teams have been offering chess scholarships and, as a result, recruiting higher-rated players for their college teams.

Doing some back-of-the-envelope analysis, my findings support this hypothesis, as the average overall rating of participants in the President’s Cup has increased substantially over the years. In the first 12 years of the cup, for instance, there were only two instances of a player with a U.S. rating over 2700 playing at least one game in the President’s Cup. In the most recent 12 years, however, there have been 40 such instances (using post-event ratings). Similarly, there were 33 instances of players with post-event ratings between 2600 and 2699 from 2001 through 2012, compared to 101 instances in the 12 most recent President’s Cups.

In other words, roughly 16% of President’s Cup participants were rated above 2600 from 2001-2012, compared to roughly 65% of participants from 2013-2025 (excluding 2020, when the tournament was not held). This is consistent with the hypothesis that more collegiate programs have put concerted effort into recruiting players rated 2600+.

This is relevant for the discussion of the gender gap because, as noted in this article, the smaller pool of women who play chess means there will be a smaller amount of women at the extremely high and low ends of the rating distribution. With so many more men than women playing chess, in other words, the odds of there being any women in a sample with super-high ratings should be small. Indeed, the highest-rated woman to play a game in a President’s Cup is WGM Sabina Foisor, whose post-event rating for the 2012 tournament was 2420. Foisor is the only woman to play at least one game in a President’s Cup with a post-event rating higher than 2400, having also done so in 2011.

This discussion is meant to suggest that the decline in female participation in the President’s Cup can be at least partially explained by the increased professionalization of collegiate chess.

I should note that this does not necessarily mean that the participation of women in collegiate chess overall is down. Many of the programs featured in the President’s Cups send more than one team to the Pan-Am, and it is common for all of the highest-rated players from a team to play on the A-team, with the next-highest group as the B team, and so on.

It is totally possible that the number of women competing in the Pan-Am has stayed the same or even increased, then, and it is even possible that the number of women competing for colleges that send a team to the President’s Cup has stayed the same or increased. It’s just that, when more and more A-teams consist entirely of 2600+-rated players, it is far less likely that any women will be on that team.

As a matter of fact, the Pan-Am began offering prizes such as Top Women’s team beginning in 2013 (thanks to Dr. Root for doing this research). Initiatives such as this would be consistent with an increase in women competing in the Pan-Am. Since 2023, the Pan-Am has split into two sections — Open and Under-1800 (team average) — further encouraging participation from college players of all skill levels, which would also be consistent with an increase in women competing in the Pan-Am.

A Call For Games

I (Alexey Root) have been contacting players, coaches, organizers, and tournament directors to locate missing President’s Cup games. Now I appeal to Chess Life Online readers for help.

All games are posted on the President’s Cup website EXCEPT the following, i.e., these President’s Cup years have missing games:

- 2013: Have 15 out of 24 games posted, the rest are missing.

- 2011: Missing two games from Round 1. The missing games from 2011 are Sipos – Bachman and Bercys – Kaplan.

- 2009: Have 9 games out of 24 possible games.

- 2008: Have 9 games out of 24 possible games.

- 2007: Have 12 games (out of 24).

- 2006: Have 13 games (out of 24).

- 2005: Have 5 games (out of 24).

- 2004: Have 4 games (out of 24).

- 2003: Have 7 games (out of 24).

- 2002: Have 10 games (out of 24).

- 2001: Have 10 games out of 36 games possible, because there were 6 boards per team playing in the inaugural President’s Cup.

If you have scoresheets of any of the missing games, please email me at Click here to show email address.

Categories

Archives

- December 2025 (24)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)