"Fred [Wren] first started to master chess in 1926. When asked what date he mastered it - he replied, "Leave that space blank, son."" (American Chess Quarterly, Spring 1962.)

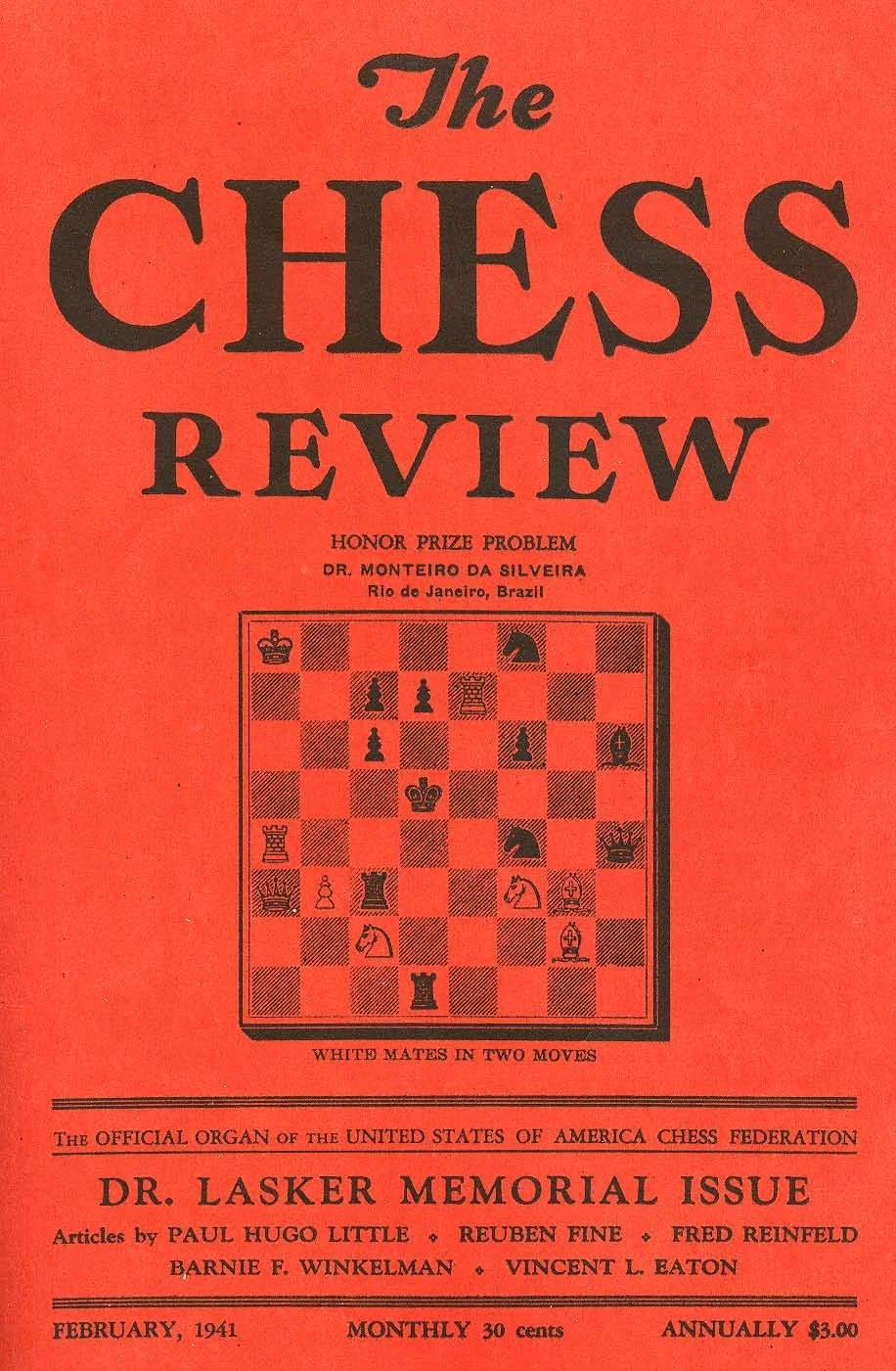

This week's Throwback comes to us from the February 1941 issue of Chess Review. Once more we see that the old truism still holds - the more things change, the more they stay the same. Keep reading after the conclusion of Wren's article to learn more about its author.

Guys We Hate Chess Review, February 1941 By Fred M. Wren The guy who “shush-shushes” everyone in the club while he is playing. He even crabs about the loud ticking of the clock. BUT, after his game is over he loudly explains why he lost, how he lost, how he had a won game but due to the racket in the room he couldn’t concentrate, etc. He then comes over to your table and after a glance at the position tells the other spectators (in whispered tones that carry to the traffic light in the next block) just how White has missed a chance to mate in three. The guy who has a chess book. He comes into the club and wants to play you. Just you. You have never lost a game to him, and can give him a Rook anytime. But he has just mastered a copy of Griffith and White, and he knows where he made his mistakes before. Remember that Ruy Lopez we played three weeks ago? Lasker says that if I had played 26.Be2 instead of 26.Qe2, Black’s game would have become untenable. And that time you played 30. … Re5, it bothered me at the time, but the notes on the Tartakower-Capablanca game in 1924 have straightened me out on that. Let’s try another Ruy Lopez. So you sit down and play a Sicilian against him, and he doesn’t know the difference, and he rushes home to his book, and you hate him just the same. The clock chiseler. You are playing a tournament game and have plenty of time on your clock. You get up after making a move, and get a drink of water. You go back to the table and see your opponent tearing his hair and wriggling in the agony common to childbirth and tournament chess. You turn away and look over some of the other games. Then a pal whispers “Your clock is going. He moved and punched the clock while you were getting a drink.” Of course, it’s your own fault. You should have looked at the clock, and not depended so much on his actions, but you still hate him. The psychologist. He has read somewhere that Lasker often made bad moves intentionally to get his opponents balled up. He plays his cuteness against your nerves, rather than his pieces against yours. He once won a game which he opened by 1.h4, and he still believes that the psychological shock of that move on his opponent was responsible for the win. In a clock game time is running low. He has two good moves, one with a Bishop and one with his King. His hand hovers over the top of the Bishop for a full minute, giving you tie to plan your answer to the move. Suddenly with the other hand he pushes a Pawn and punches the clock. This of course is more shock stuff. He seldom wins with these tactics, but no one can hate you for hating him. The analyst. He is a better player than you are and he beats you in a nice game. Just as you are ready to go home, he mentions that on the 21st move you had a chance for a fine combination. You don’t remember it. He sets the pieces up just as they were before your 21st move. They don’t look right to you. You check over the game score and find out that he has the right position. He then shows you where you could have forced resignation through a five move combination. He’s right, and his analysis is right. Maybe that’s why you hate him.

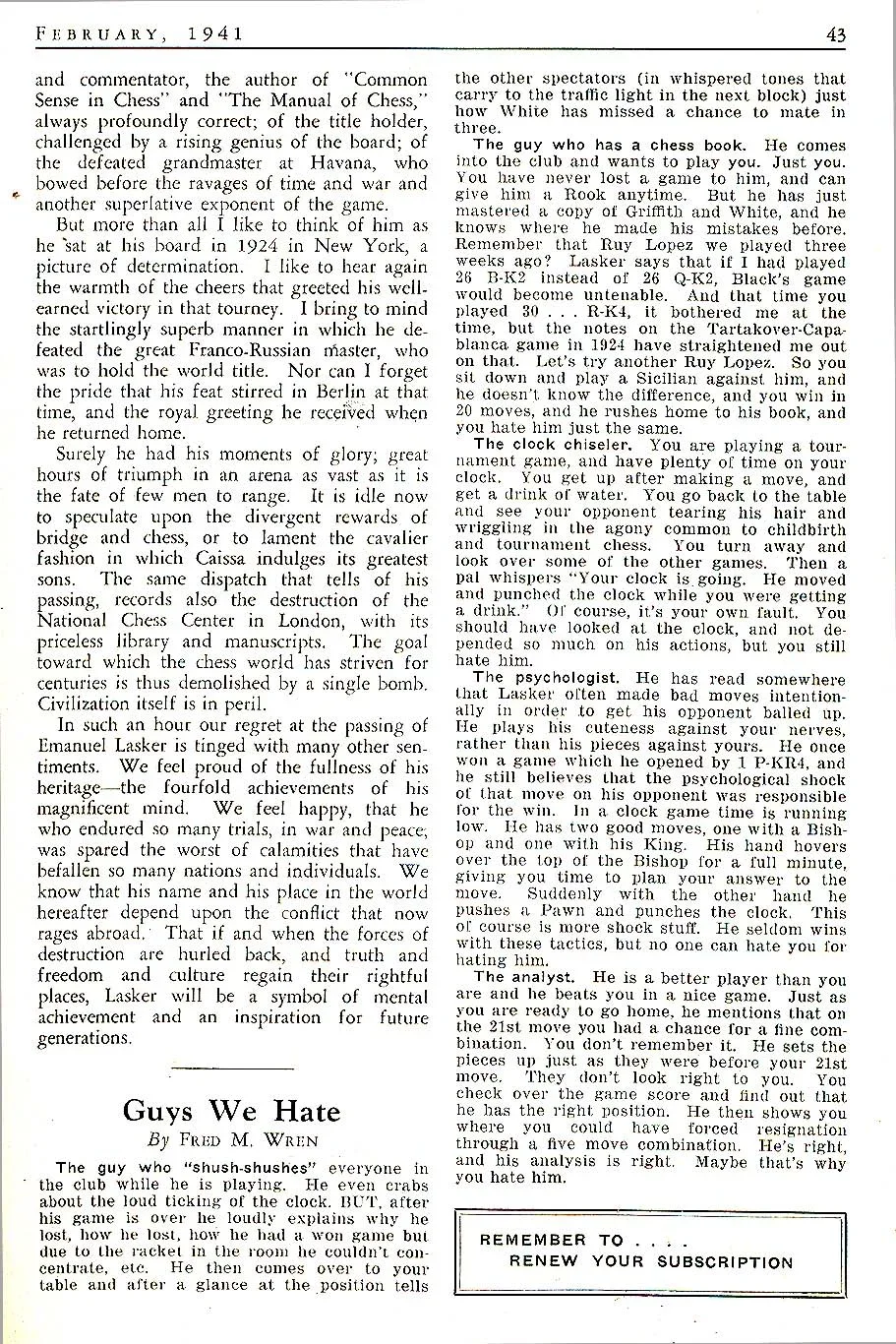

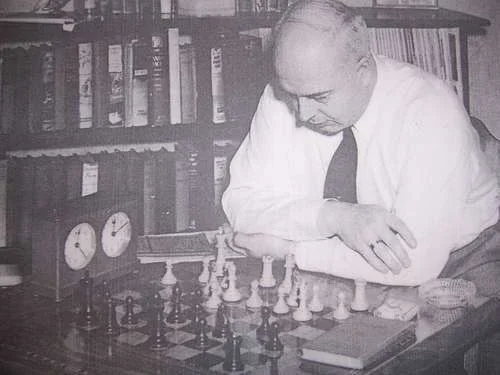

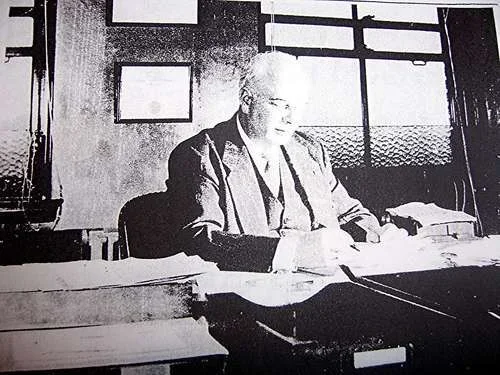

Commentary: This week’s Throwback turned out to be a real YouTube hole. (For those of you above the age of 23, a YouTube hole is what happens when you search for one video on YouTube, look up, and realize that four hours and dozens of videos have passed without your knowledge.) It was originally conceived as a simple re-transmission of a February 1941 article from Chess Review. As so often happens, the “story behind the story” turned out to be just as interesting. I first read Fred Wren’s “Guys We Hate” in The Best of Chess Life & Review, 1933-1960, an anthology collected and edited by Bruce Pandolfini. I must have checked this book out from my local library dozens of times in my youth, along with its successor volume, The Best of Chess Life & Review, 1960-1988. Pandolfini did yeoman’s work in his selection process, choosing to include the complete Chess Review report on AVRO 1938, heaps of well-annotated games, and tales of the rise and fall of Bobby Fischer. Volume 2 finishes with a 1988 Chess Life story about a very young Josh Waitzkin. If you get a chance to read one or both titles, do so. You won’t regret it. Fred Wren’s story stands out, even among the jewels collected in these anthologies. Its humor is timeless – while some of the references are dated, its essence, its eidos, is as true now as it was in 1941. Clocks no longer tick, and we might replace “the guy who has a chess book” with “the guy who asked Stockfish,” but everyone knows someone at the club who is just like one of Wren’s dramatic personae. And we most certainly still hate them. That Fred Wren could write will not be news to readers of a certain age. He was a prodigious contributor to many chess periodicals, including Chess Review, Chess Life, the American Chess Quarterly, Canada’s Chess Chat, England’s Chess, and Schaak-Mat from the Netherlands. Wren called himself a “woodpusher,” which is ironic given his over-the-board skill, and he is perhaps best known for his “Tales of a Woodpusher” series for Chess Review in the late 1940s. Wren also served as Chess Life’s editor from 1958-1960. Born in 1900 in Sherman, Maine, Fred Wren fought in World War I, and spent most of his professional career in government service. He worked for the U.S. Immigration Service for 22 years, with posts across Europe and the Canadian border, and another 10 years in the employ of the State Department. Here too his writing talents were evident, as he was recruited to be one of the authors of State Department technical manuals used across the globe. A basketball fan and coach away from the board, Wren was married with two children. He died in 1978. ***Special thanks to Daniel DeLuca of chessmaine.net for providing materials used in the preparation of this week's Throwback. You can read his outstanding and detailed appreciation of Fred Wren at chessmaine.net. Thanks also to Helen Gruber-Wren (via Dan DeLuca) for the photos reproduced here.

Guys We Hate Chess Review, February 1941 By Fred M. Wren The guy who “shush-shushes” everyone in the club while he is playing. He even crabs about the loud ticking of the clock. BUT, after his game is over he loudly explains why he lost, how he lost, how he had a won game but due to the racket in the room he couldn’t concentrate, etc. He then comes over to your table and after a glance at the position tells the other spectators (in whispered tones that carry to the traffic light in the next block) just how White has missed a chance to mate in three. The guy who has a chess book. He comes into the club and wants to play you. Just you. You have never lost a game to him, and can give him a Rook anytime. But he has just mastered a copy of Griffith and White, and he knows where he made his mistakes before. Remember that Ruy Lopez we played three weeks ago? Lasker says that if I had played 26.Be2 instead of 26.Qe2, Black’s game would have become untenable. And that time you played 30. … Re5, it bothered me at the time, but the notes on the Tartakower-Capablanca game in 1924 have straightened me out on that. Let’s try another Ruy Lopez. So you sit down and play a Sicilian against him, and he doesn’t know the difference, and he rushes home to his book, and you hate him just the same. The clock chiseler. You are playing a tournament game and have plenty of time on your clock. You get up after making a move, and get a drink of water. You go back to the table and see your opponent tearing his hair and wriggling in the agony common to childbirth and tournament chess. You turn away and look over some of the other games. Then a pal whispers “Your clock is going. He moved and punched the clock while you were getting a drink.” Of course, it’s your own fault. You should have looked at the clock, and not depended so much on his actions, but you still hate him. The psychologist. He has read somewhere that Lasker often made bad moves intentionally to get his opponents balled up. He plays his cuteness against your nerves, rather than his pieces against yours. He once won a game which he opened by 1.h4, and he still believes that the psychological shock of that move on his opponent was responsible for the win. In a clock game time is running low. He has two good moves, one with a Bishop and one with his King. His hand hovers over the top of the Bishop for a full minute, giving you tie to plan your answer to the move. Suddenly with the other hand he pushes a Pawn and punches the clock. This of course is more shock stuff. He seldom wins with these tactics, but no one can hate you for hating him. The analyst. He is a better player than you are and he beats you in a nice game. Just as you are ready to go home, he mentions that on the 21st move you had a chance for a fine combination. You don’t remember it. He sets the pieces up just as they were before your 21st move. They don’t look right to you. You check over the game score and find out that he has the right position. He then shows you where you could have forced resignation through a five move combination. He’s right, and his analysis is right. Maybe that’s why you hate him.

Commentary: This week’s Throwback turned out to be a real YouTube hole. (For those of you above the age of 23, a YouTube hole is what happens when you search for one video on YouTube, look up, and realize that four hours and dozens of videos have passed without your knowledge.) It was originally conceived as a simple re-transmission of a February 1941 article from Chess Review. As so often happens, the “story behind the story” turned out to be just as interesting. I first read Fred Wren’s “Guys We Hate” in The Best of Chess Life & Review, 1933-1960, an anthology collected and edited by Bruce Pandolfini. I must have checked this book out from my local library dozens of times in my youth, along with its successor volume, The Best of Chess Life & Review, 1960-1988. Pandolfini did yeoman’s work in his selection process, choosing to include the complete Chess Review report on AVRO 1938, heaps of well-annotated games, and tales of the rise and fall of Bobby Fischer. Volume 2 finishes with a 1988 Chess Life story about a very young Josh Waitzkin. If you get a chance to read one or both titles, do so. You won’t regret it. Fred Wren’s story stands out, even among the jewels collected in these anthologies. Its humor is timeless – while some of the references are dated, its essence, its eidos, is as true now as it was in 1941. Clocks no longer tick, and we might replace “the guy who has a chess book” with “the guy who asked Stockfish,” but everyone knows someone at the club who is just like one of Wren’s dramatic personae. And we most certainly still hate them. That Fred Wren could write will not be news to readers of a certain age. He was a prodigious contributor to many chess periodicals, including Chess Review, Chess Life, the American Chess Quarterly, Canada’s Chess Chat, England’s Chess, and Schaak-Mat from the Netherlands. Wren called himself a “woodpusher,” which is ironic given his over-the-board skill, and he is perhaps best known for his “Tales of a Woodpusher” series for Chess Review in the late 1940s. Wren also served as Chess Life’s editor from 1958-1960. Born in 1900 in Sherman, Maine, Fred Wren fought in World War I, and spent most of his professional career in government service. He worked for the U.S. Immigration Service for 22 years, with posts across Europe and the Canadian border, and another 10 years in the employ of the State Department. Here too his writing talents were evident, as he was recruited to be one of the authors of State Department technical manuals used across the globe. A basketball fan and coach away from the board, Wren was married with two children. He died in 1978. ***Special thanks to Daniel DeLuca of chessmaine.net for providing materials used in the preparation of this week's Throwback. You can read his outstanding and detailed appreciation of Fred Wren at chessmaine.net. Thanks also to Helen Gruber-Wren (via Dan DeLuca) for the photos reproduced here.

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (6)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)