Editor's note: Some of us have the luxury of traveling to tournaments whenever we want without hesitation. Others have to pick one or two events a year and plan accordingly. But many of us are somewhere in between: we can make relatively last-minute decisions to play. But at what cost? Aakaash Meduri shares his thought process behind deciding to play in Las Vegas at the last minute.

I wasn’t supposed to play in the North American Open.

Really, I wasn’t. Yet on a Christmas Eve spent with my father, I began thinking about it. You see, I was supposed to spend the holidays with my family. I work at an early-stage startup where PTO is a luxury. I really did want to spend the time with them. But with my brother’s last-minute Amtrak ticket to hang out with his girlfriend and my mother working her typical ER Nurse hours, what choice did I have?

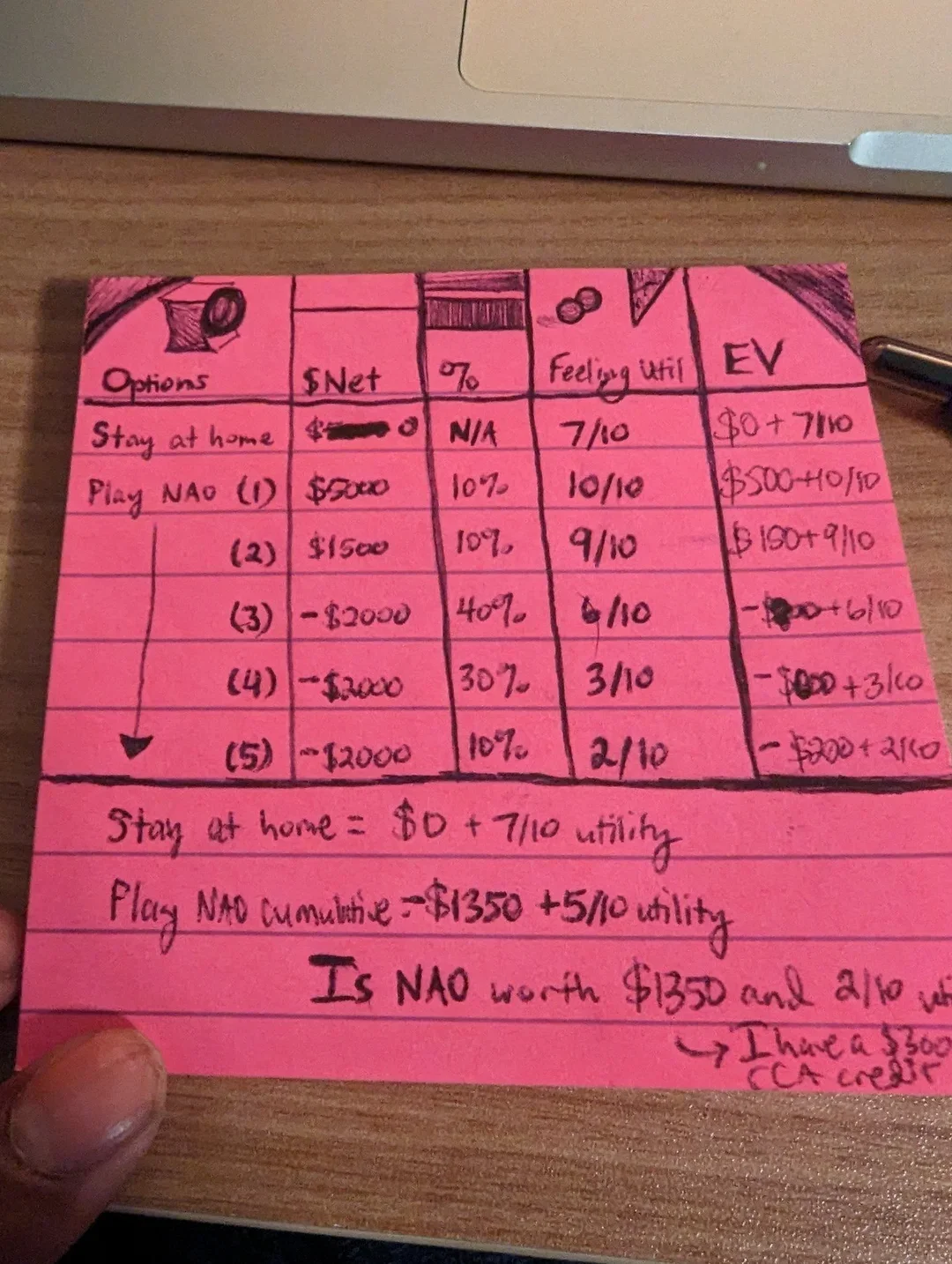

I began doing what any normal person would. I sketched out a decision matrix. On it was a rough range of outcomes, my net financial gain or loss, and a “feel-good” (i.e., how good will I feel ditching my family to play chess) utility metric. The result? I would likely leave Vegas down at least $600 and feel like a 6/10 in the process.

Good enough! Never mind that I severely underestimated the cost of flight tickets amidst a brutal holiday travel season. I was sold.

A brief background on my history with the North American Open. I’d played this event three times before. First in 2016 when I lost 28 rating points. Then in 2017 losing 29 points. And finally, the crème de la crème 2018 edition when I dropped 44 rating points. North American Open has single handedly cost me just over 100 rating points. I’m like Adam Sandler in Uncut Gems.

So why did I decide to play? Call it the perpetual optimism of a chess player. I recently moved to New York City where I’d been spending a ton of time at the Marshall Chess Club. My rating graph had taken a sort of “U” curve, but I was on the right half of the U. I felt in form and wanted to test myself outside the storied walls of the Marshall.

So I made myself a promise. I would go to Vegas to play chess. No poker. No roulette. No blackjack. No gambling. Just chess.

An oxymoron. All chess players know you sometimes need to roll the dice and get lucky.

I'd had quite a strong performance leading up to the penultimate round, dropping just two draws - one against a 2000 who was having a spectacular event and another against an IM.

I chose to present the following game with minimal commentary, not because it lacks intrigue but rather to set the stage for my final round clash.

Leaving my sixth round, I was on an adrenaline high. It was my second game of the tournament to finish last in the entire ballroom of 500+ games. But then quickly, the crash followed. I was mentally and emotionally exhausted from not converting such a great position. I was tilted.

There is a meme concept in programming called the Ballmer Peak. According to the Ballmer Peak, there is a narrow range of alcohol consumption which leads to peak performance. A friend at the tournament suggested I drink some wine to calm my nerves, and I thought why not? I’m already out of the top prizes anyway.

Calming my nerves took a little longer than expected, however. But I decided I would rather show up grounded than on time to my last game.

A final score of 5½/7 was enough to share third place, win some money, and propel my live rating back over 2200 for the first time since 2017. Looking back at the decision matrix, I slightly overperformed my expected value both monetarily and with the feel-good utility. I’ll admit, it feels almost robotic to assess the tournament in such a way. Where’s the romanticism?

GM Jan Hein Donner wrote in 1959, “Chess is not art. No, chess cannot be compared with anything. Many things can be compared with chess, but chess is only chess.” I’m not rated high enough to ascertain if Donner was being tongue-in-cheek or he really meant this. Nevertheless, I can’t help walking away from the North American Open with an altered perspective.

Chess is life in the sense that our tendencies outside the board often manifest over the board. This may sometimes lead us to ruin, but it can also lead us to victory. In my natural state, I enjoy gambling. There’s this thrill that comes with embracing uncertainty and placing a bet. I stuck to my promise of avoiding any table games in Vegas, and I believe quelling those distractions helped me embrace the beauty of each game and place smarter bets on the chess board. Remove the romanticization of the external elements surrounding chess to appreciate and live the chess itself.

Maybe it’s a low-effort justification for a good tournament performance. All I know is, I’ll probably be back at the North American Open to test my luck again.

Categories

Archives

- December 2025 (25)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)