“The most important thing is self-confidence. So many people will doubt your abilities in life---never listen to them. If you do not truly believe that you can make it to the Grandmaster title, for example, you will never do so.” -Jacob Aagaard, Excelling at Chess

Early in my chess career, when I was 10-years-old, my parents took my younger sister and me to an all-girls event for some of the young female talents in the area, featuring a Woman International Master. It started with a lecture about her views on chess, and then she played a simul against all of the girls. I don’t remember her lecture or my game in the simul. What I remember is that something felt very off about the event to me, even if I didn’t know enough about the subject yet to be able to express it in words. I knew that the people who organized the event as well as the WIM herself had the best intentions: encouraging more girls to continue playing chess and showing the girls a potential role model, a titled female player. The WIM, however, was US Chess rated around 1800. I was only rated about 1100 at the time. I knew that an 1800 player was stronger than me and that it took work to get there, but I also knew that it was a level that would not otherwise be revered---if she wasn’t a Woman International Master. I remember my 10-year-old self trying to intentionally look unimpressed during the event. I wanted the adults in the room and anyone else who saw me to know that this wasn’t my role model. It really bothered me that the adults believed that I would have an 1800 player as a role model, just because I was a girl. My favorite players were World Champions Jose Capablanca and Mikhail Tal. All of my coaches (with the exception of when I was a sheer beginner) had always been, at least National Master level, if not IM or GM level. I wanted to be a great player, not a great player for a girl. I believe that this mentality, and my high standards helped me improve quickly when I was young. By the next year, I had already crossed the 1800 mark myself. There is a very high focus on getting girls and women to start and continue playing chess. But, not all incentives are equal: Which are helping to inspire these players for future universally high levels of success? In 2009, the subject of women’s titles hit mainstream news. The Wall Street Journal published, “Abolish Women’s Chess Titles” by Barbara Jepson.

“The time has come to drop gender-segregated titles for women, which make even less sense today than when they were introduced in 1950 (WIM) and 1976 (WGM).” -Barbara Jepson, “Abolish Women’s Chess Titles”

While this article was well-intentioned and featured quotes from several of the top female players, it didn’t cover the main arguments for and against women’s titles or what the titles are mainly used for today. In addition, Jepson isn’t involved in the chess world, and many took issue with the article because of this. The most notable response to Jepson’s article was “Abolish Women’s Titles? Ridiculous!” by former Women’s World Champion Alexandra Kosteniuk, who speculates that Jepson knows “close to nothing about professional chess herself”. Kosteniuk’s article also explains in detail many of the main arguments in favor of women’s titles, which I’ll explore in the “Pros vs. Cons” section. However, before discussing whether the titles should or shouldn’t be eliminated (and my personal opinion), I’d like to examine some of the facts about them.

The Facts

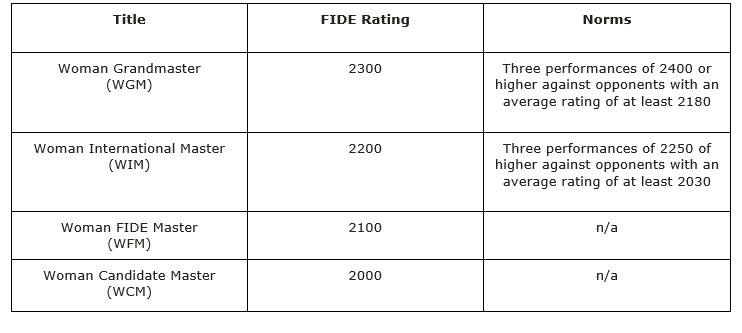

1. There are currently 4 women-only titles awarded by FIDE, the World Chess Federation, for rating and norm based achievements.

Women’s Title Qualifications

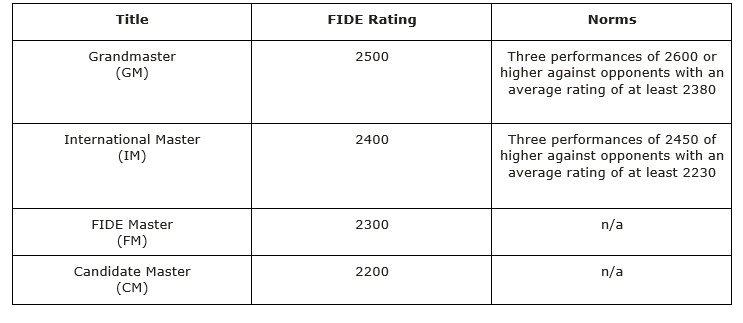

2. Compared to the general (non-gendered and open to all) titles, women's titles require ratings and norm performances of 200 rating points lower.

General Title Qualifications

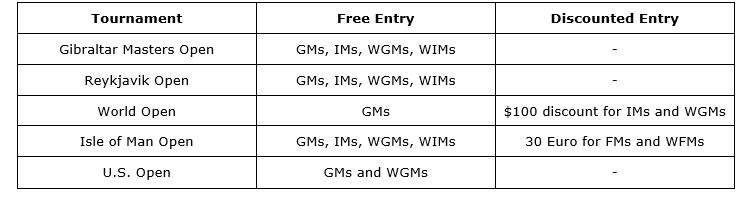

3. Players who hold women's titles can receive financial perks at tournaments.

Many tournaments offer free or cheaper entry to those holding certain FIDE titles. Women holding WGM and WIM titles often receive the same benefits as players who hold the general GM and IM titles, which makes competition more affordable to female players. Here are a few examples from some of the most prominent open tournaments in the world:

Pros & Cons

1. Are women’s titles encouraging for women?

In “Abolish Women’s Titles? Ridiculous!”, Kosteniuk asserts that women’s titles are essential for encouraging female chess players:

“...abolishing all the women's titles, such as Woman Grand Master (WGM), and WIM (Woman International Master), and logically all the women titles below that, would just make it less interesting for women players to play.” -Alexandra Kosteniuk, “Abolish Women’s Titles? Ridiculous!”

However, one of the reasons Kosteniuk supports women’s titles is her belief that men have an innate physical advantage in chess:

“Physical strength and therefore the ability to concentrate and thus not to make mistakes is higher in men's chess and that's also another reason why, in the long term, men are showing greater results.” -Alexandra Kosteniuk, “Abolish Women’s Titles? Ridiculous!”

Supporting women’s titles as encouragement by claiming that women have less natural chess ability is counterintuitive: How can that idea be encouraging to any woman? In addition, Kosteniuk’s claim that greater physical strength leads to a greater ability to concentrate is not supported by any concrete data.

“Chess is an intellectual sport, physical strength is by far not the key factor there.” -Natalia Pogonina, “Women and Men in Chess: Smashing the Stereotypes”

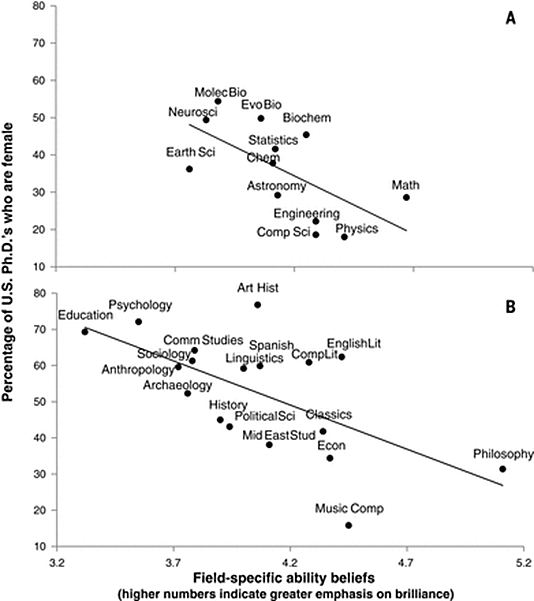

In fact, lower expectations may be the very reason why less women play competitive chess in the first place. An article on Chessbase News, “Women in Chess: The Role of Innate-Ability Beliefs” by Professor Wei Ji Ma, explores this possibility. Using a study on the gender gap in different academic subjects, Professor Ma considers the possibility that women may avoid fields that are believed to require brilliance---because society is more likely to associate brilliance with males.

“A recent article in Scientific American Mind begins:’Try this simple thought experiment. Name 10 female geniuses from any period of history. Odds are you ran out of names pretty quickly’. The thought experiment can be adapted: try to name 10 female figures in popular culture who—like Sherlock Holmes, Dr. House, or Will Hunting—are characterized by their innate brilliance, their raw intellectual firepower. As before, one rapidly runs out of names. Whatever the cause, the message is clear: women are not culturally associated with such inherent gifts of genius. The consequences of this stereotype are likely wide-ranging. In the current study, we focus on one of these consequences, asking whether such a pervasive cultural message might have a role in shaping individuals’ academic and career paths. Specifically, if it is widely believed that men tend to possess more intellectual ability than women, then women may be discouraged from entering into fields that are thought to require this ability.” -Meredith Meyer, Andrei Cimpian, Sarah-Jane Leslie, “Women are underrepresented in fields where success is believed to require brilliance”

The research finds a strong correlation between gender gaps and fields where “genius” is emphasized (whether or not the emphasis in genius is justified):

“The more emphasis on brilliance, the lower the proportion of female PhDs. For example, mathematicians (whether male or female) widely believe that you have to be a genius to be successful, whereas neuroscientists (whether male or female) consider hard work to be more important; neuroscience produces a much larger proportion of female PhDs than mathematics. Philosophers believe that innate ability is critical, education scientists not so much; education produces a much larger proportion of female PhDs than philosophy.” -Wei Ji Ma, “Women in Chess: The Role of Innate-Ability Beliefs”

Interestingly, this correlation was present across the sciences and humanities alike.

Graph: Percentage of female Ph.D's compared to a Subject's Reputation of Requiring Brilliance

Comparing these findings to the gender gap in participation in chess, this leads us to consider: Could the existence of women’s titles and the lower standards associated with them actually be driving women away from chess?

Comparing these findings to the gender gap in participation in chess, this leads us to consider: Could the existence of women’s titles and the lower standards associated with them actually be driving women away from chess?

“Parents google “is my son gifted?” 2.5 times as often as ‘is my daughter gifted?’ Authors like Lisa Bloom, politicians like Jo Swinson, and even a campaign by Verizon Wireless have pointed out that girls get praised for their looks, while boys get praised for their smarts. The belief that mostly men are geniuses is further promoted by popular culture, from Good Will Hunting to House M.D., and persists among highly educated adults: on RateMyProfessors.com, the word “genius” is used much more for male than for female professors. Objectively, there is no scientific basis for claiming that women are less brilliant than men; for example, in American schools, girls are 11% more likely to be in a gifted program than boys.” -Wei Ji Ma, “Women in Chess: The Role of Innate-Ability Beliefs”

.

2. Gendered titles often lead to misunderstandings.

“It’s a taxing effort to explain to journalists or chess laymen the difference between woman grandmaster and grandmaster and how 20 women have the ‘real grandmaster’ title.” -Jennifer Shahade, “Jennifer on Women’s Titles”

Separate women’s titles often give those outside of or new to the chess world an inaccurate impression of how segregated chess is:

“...professional chess is facing serious questions about gender equality. The way the professional league (also known as the World Chess Federation) works now is that there is a larger league and a smaller league. The parent league is gender neutral and competes for the title of Grandmaster. The smaller league is exclusive to women and competes for the title of Woman Grandmaster.” -Elizabeth John, New York Minute Magazine

While there are women’s tournaments, there is no separate women’s league. Furthermore, most tournaments, especially in the U.S., are not gendered at all. I think I’ve played in one women-only event in my entire chess career. I’ve even heard people mistakenly speculate that there are entirely different rating systems for men and women. In an article in Toronto Standard, which describes the Chess Federation of Canada’s creation of a Woman National Master and a Woman Candidate Master title in 2013, one journalist, states:

“Although women can technically compete against men in open tournaments, females have their own set of ratings.” -Tiffy Thompson in Toronto Standard

This kind of misunderstanding is especially problematic because it can undermine the hard-earned ratings of female players.

WGM = GM?

“Nobody has ever said that WGM is equivalent to GM, everybody knows it's not the case…” -Alexandra Kosteniuk, “Abolish Women’s Titles? Ridiculous!”

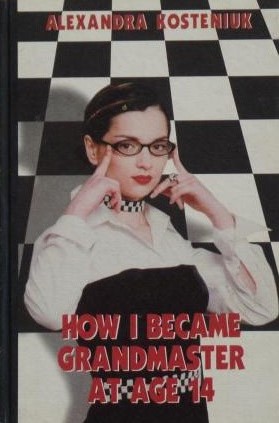

An example of the Woman Grandmaster title being mistaken for the Grandmaster title is seen in a book written (coincidentally) by Kosteniuk in 2001, titled, How I Became a Grandmaster at Age 14. Kosteniuk did not become a grandmaster at age 14---What she meant was how she became a Woman Grandmaster at age 14. The choice to drop the word "Woman" from the title was likely a publishing/marketing decision, meant to make the title more concise and catchier. However, since Grandmaster and Woman Grandmaster are two distinctly different titles with completely different requirements, the title is misleading. In fact, in an article in the Telegraph, a journalist mistakenly claims:

An example of the Woman Grandmaster title being mistaken for the Grandmaster title is seen in a book written (coincidentally) by Kosteniuk in 2001, titled, How I Became a Grandmaster at Age 14. Kosteniuk did not become a grandmaster at age 14---What she meant was how she became a Woman Grandmaster at age 14. The choice to drop the word "Woman" from the title was likely a publishing/marketing decision, meant to make the title more concise and catchier. However, since Grandmaster and Woman Grandmaster are two distinctly different titles with completely different requirements, the title is misleading. In fact, in an article in the Telegraph, a journalist mistakenly claims:

“At 14 years old, Miss Kosteniuk became a chess grandmaster, the youngest woman in the world to attain the title.”

Grandmaster at 14 would've meant breaking Bobby Fischer's and Judit Polgar's records (Both earned the GM title at age 15). To this day, only 27 people in the entire history of chess have earned the grandmaster title before their 15th birthday, including Hou Yifan---who was actually the youngest female in the world to do so (at age 14 and 6 months).

Note: This is not to say that the book itself isn't worth a read. And Kosteniuk has now, in fact, earned the general grandmaster title (in 2004, at age 20).

Unfortunately, when referring to the WGM title, it’s not uncommon for people to drop the “W”, treating it as the equivalent to GM.

“I’ve always wanted to go by the more general title. Female titles require less stringent norms and a smaller rating. I just never really got the idea of a WIM. Why? What’s a WIM compared to regular IM? So, I got my FIDE rating to 2300, and I went by FM.” -Alisa Melekhina in an interview with Daaim Shabazz of The Chess DrumFIDE Master Alisa Melekhina at the 2016 U.S. Women's Championship. Photo Spectrum Studios

At weekly tournaments at a local chess club, I’ve regularly overheard the tournament director and some of the players claim that there are “two GMs” competing---when actually referring to one GM and one WGM. Grandmaster is the highest rating and norm based title, representing the pinnacle of chess achievement. The requirements for the WGM title are below those for the general IM title. Treating these two very different achievements as the same undermines all of the tremendous effort required for those who have earned the grandmaster title. In addition, equating WGM to GM deducts from the fact that women are fully able to earn the more stringent grandmaster title.

Grandmaster Irina Krush at the 2017 U.S. Women’s Championship

Grandmaster Irina Krush at the 2017 U.S. Women’s Championship.

3. Lower Expectations = Lower Results

“I don’t see their benefit. Women’s titles are really a marker of lower expectations.” -Irina Krush, "Abolish Women's Chess Titles"

The greatest risk of women’s titles is that they set up a lower standard of achievement for female players (200 rating points lower). Nearly every great chess player has emphasized the importance of confidence for success.

“You need to have that edge, you need to have that confidence, you need to have that absolute belief that you’re the best and that you’ll win every time.” –Magnus Carlsen

“I grew up in what was a male dominated sport, but my parents raised me and my sisters [to believe] that women are able to reach the same result as our male competitors if they get the right and the same possibilities.” -Judit Polgar, TIME Magazine

“Winning is not a secret that belongs to a very few, winning is something that we can learn by studying ourselves, studying the environment and making ourselves ready for any challenge that is in front of us.” -Garry Kasparov

Lower expectations can affect a player’s confidence at the board. A loss of confidence can affect the performance of even the strongest players.

“At some point, he seemed to lose all confidence trying to break down the Berlin Wall. He was still fighting as only Kasparov can, but I could see it in his eyes that he knew he wasn’t going to win one of these games.” -Vladimir Kramnik on his World Championship match victory against Kasparov in 2000

How much can lower expectations affect performance? This question has been explored in detail for an ability considered related to chess, mental rotation. Mental rotation is the ability to rotate mental representations of 2D and 3D objects.

“And I started thinking about it and asking myself, “OK, what exactly does this rotation skill require?” And it seems to me that it requires being able to make a series of complicated changes to a three dimensional object, and then to be able to see it clearly. And that sounds almost exactly like chess calculation to me.” -Elizabeth Vicary, “E. Vicary on Chess, Girls and Genius”

In addition, mental rotation (comparable to chess) is an area where, on average, men have outperformed women. Traditionally, this has been attributed to inherent biological differences between males and females. However, a 2009 study examined the question “Are males always better than females in mental rotation?”---testing if lower expectations based on gender can affect female performance in mental rotation tests. The study found that the results of both men and women changed depending on the expectations set up before the test. When participants were told that men perform better, the men scored higher. However, when told that women generally perform better on the test, the genders performed nearly identically.

In the study, male and female participants were divided into 3 groups, each given a mental rotation test with different instructions:

- Men are better than women at this task

- Women are better than men at this task

- Control instructions with no gender reference

Note: In the control group, gender was not referenced before the test. However, the participants may've come into the test with preconceived gender expectations because of the widely accepted belief that males are innately better at mental rotation. “Taken together results suggest that, regardless of gender, a subject increases performance when gender superiority is suggested by the given instructions.” - Angelica Moe, “Are males always better than females in mental rotation? Exploring a gender belief explanation”, ScienceDirect

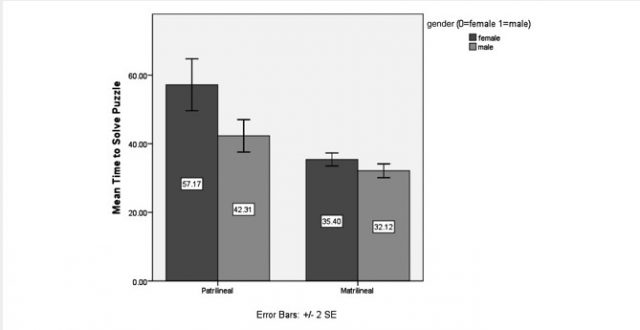

The effect of gender-based lower expectations in spatial ability has been tested since with a larger sample (nearly 1300 people) in a very unique way: by comparing the gender gap in spatial abilities between two tribes in Northeast India---one with a patrilineal society and one with a matrilineal society.

“One tribe, the Karbi, is patrilineal, meaning that men own most property and inheritance always goes to the oldest son. A second tribe, the Khasi, is matrilineal. The youngest daughter inherits the property in Khasi villages and men are forbidden to own land. -Stephanie Pappas, ”Culture Drives Gender Gap in Spatial Abilities, Study Finds”

The aim of the study was to answer the question:

“Could this gender gap in spatial reasoning be substantially driven by nurture?” -Moshe Hoffman, Uri Gneezy, and John A. List,“Nurture affects gender differences in spatial abilities”

This study was able to test for the effect of nurture more directly than other studies because both tribes “share a genetic background”:

“The advantage of going to rural India to study these two tribes is that they're biologically and geographically very similar. We have this beautiful control group where they live literally right next door. These villages are kind of interspersed with each other, and the tribes diverged genetically only a few hundred years ago.” -Moshe Hoffman, study author,”Culture Drives Gender Gap in Spatial Abilities, Study Finds”

A key difference between the two societies was the amount of education provided to men and women. In the matrilineal society, men and women received an equal number of years of education while, in the patrilineal society, men received 3.67 more years of education. Again, the results of the genders changed depending on the situation. In the patrilineal society, females performed worse by spending significantly more time to solve a puzzle than males. However, in the matrilineal society, the gender gap in solving time closed significantly.

“In this study, we use a large-scale incentivized experiment with nearly 1,300 participants to show that the gender gap in spatial abilities, measured by time to solve a puzzle, disappears when we move from a patrilineal society to an adjoining matrilineal society.” -Moshe Hoffman, Uri Gneezy, and John A. List, “Nurture affects gender differences in spatial abilities”

Note: A lower bar indicates a faster solving time, which indicates a higher measure of spatial ability. Thus, lower bar = higher spatial abilityInterestingly, both the men and women in the more egalitarian (at least in terms of education) matrilineal society performed better than those in the patrilineal society.

From these results, the study concluded that:

“...even while holding biology constant, there is an effect of culture on the gender differences in spatial abilities." -Moshe Hoffman, ”Culture Drives Gender Gap in Spatial Abilities, Study Finds”

What do these results mean for women in chess? On a smaller scale, researchers have tested the effect of gender-based lower expectations in chess directly. In “Checkmate? The role of gender stereotypes in the ultimate intellectual sport”, female chess players were paired against a male opponent of a similar rating (within 30 elo points) for 2 online rapid games. In one of the games, the women players were told that their opponent was male. In the other game, the women were told that their opponent was female (even though they were actually playing a second game with the exact same male opponent). When the women inaccurately believed that they were playing against other women, they scored close to 50%. When it was revealed that they were playing against a man, their score dropped to 25%. In addition, the women approached the game with less confidence and less aggressively when they were told their opponent was male. The researchers surmised that "widely held gender stereotypes" could be the cause.

"Hence, a motivational perspective may be better suited to understand (and prevent) the underperformance of women in the ‘ultimate intellectual sport.’" -Anne Maass, Claudio D’Ettole, and Mara Cadinu, “Checkmate? The role of gender stereotypes in the ultimate intellectual sport”

Considering the research done so far, it is likely (and intuitive) that people perform better when they don’t face a lower expectation based on their gender.

“It is common to hear a chess-playing girl say that she aspires to become a “WIM” or “WGM” because women’s titles are taken as the natural stage of improvement. Unfortunately, one hardly hears a girl mentioning the coveted “IM,” “GM” titles as an initial goal despite the fact that they aspire to compete with the best in every other endeavor. By this default, boys will have higher chess goals, higher expectations and thus, more ambition. Have we pigeon-holed girls and women to think only in terms of gender-related events and lesser titles? Have we encouraged them to have lower expectations of their abilities?” -Daaim Shabazz,“Jamaica’s Deborah Porter makes history… what’s next?“

.

4. If women’s titles were eliminated, should women’s tournaments be eliminated, too?

“Women's tournaments and training allow an underrepresented population in the chess world to make friends and help organizers to promote women in chess to the media and community.” -Jennifer Shahade, “Jennifer on Women’s Titles”

Some, including Kosteniuk, have suggested that if women’s titles are eliminated, women’s tournaments would have to be eliminated as well.

“If we would accept the reasoning that women's titles should be abolished, we should also abolish all women-only championships, and all professional women chess players (well, maybe a handful would survive) would lose the little prize money FIDE and organizers offer them the opportunity to get.” -Alexandra Kosteniuk, “Abolish Women’s Titles? Ridiculous!”

I think there is a big difference between women’s titles and women’s tournaments. While women’s titles are are directly associated with a 200 rating point lower standard of achievement, tournaments do not come with automatically lower requirements.

“The arguments I fall back on to explain women’s tournaments like financial incentives and positive examples for the community and the media, don’t work as well when trying to justify women’s titles. In an academic analogy, there are women's colleges, women's conferences, even anthologies of women's work but there are no WBAs or WPHDs.” -Jennifer Shahade, “Jennifer on Women’s Titles”

Women-specific competitions are meant to offer a space where female chessplayers (often 5% or less of the average tournament setting) can feel represented and more easily meet other female players.

“I think if we view those events in that aspect that we’re trying to bolster the game as a whole rather than make any objective assessments about how good women are, how valuable the title is in any tournament. I think as long as we keep that in mind that would make those tournaments less contentious. I think they’d be a lot more respected.” -Alisa Melekhina in an interview with Daaim Shabazz of The Chess Drum

Women’s prizes at open tournaments are another tricky subject, but at least they don’t create a 200 rating point lower performance expectation. In some cases, despite the existence of women’s tournaments and prizes, women have won the overall event:

Grandmaster Hou Yifan, currently the highest ranked woman in the world, at the 2016 St. Louis Showdown. Photo: Spectrum Studios

Grandmaster Hou Yifan, currently the highest ranked woman in the world, at the 2016 St. Louis Showdown. Photo: Spectrum Studios- In 2012, Hou Yifan tied for 1st place overall at the Tradewise Gibraltar Chess Festival while simultaneously winning the “Top Woman” prize as well as the “Top Junior” prize.

The 2016 National Junior High Champion Maggie Feng at this year’s U.S. Women’s Championship.

The 2016 National Junior High Champion Maggie Feng at this year’s U.S. Women’s Championship.- Even though there is a separate “All-Girls National Championship”, last year’s overall National Junior High Champion was Maggie Feng.

- Although there is currently a National Girls’ Tournament of Champions, the overall Arnold Denker High School Tournament of Champions was won by a female, Abby Marshall, in 2009.

- In 2013, Grandmaster Alexandra Kosteniuk became the first person to win both the overall Swiss Championship and the Women’s Swiss Championship simultaneously.

- After 1990, Judit Polgar refused to compete in any “women-only” tournaments. That same year, she won the under-14 open section (called the “boys section” at the time) of the World Youth Championships. After that, despite being a clear candidate to be Women’s World Champion as the top ranked woman in the world, Polgar competed in only the overall World Championship cycle, qualifying for the World Cup, the Candidates Tournament, and the 2005 FIDE Knock-out World Chess Championship, ultimately breaking into the top 10 in the world with a peak rating of 2735 and a peak ranking of 8th in the world overall.

“Thanks to the Polgars the adjective 'men's' before events and the 'affirmative action' women's titles, such as Woman Grandmaster, have become anachronisms (though they are still in use).” -Garry Kasparov

.

5. Intermediate titles can motivate and show progress.

One aspect to consider is that it may be easier to find women’s titles superfluous when you’re not that far from the general FIDE titles. For players who start playing competitive chess later in life or have less access to resources, the general FIDE titles may seem less accessible.

“...for me personally, trying to obtain the WIM title was a big motivation. Given the time I want to invest in chess, becoming a grandmaster is simply not an option, but the goal of WGM does seem possible.” -Arlette van Weersel, “Abolishing Women’s Titles: A Different Perspective”

One of the biggest arguments in favor of women’s titles is that they give players that aren’t within range of the general titles something to aim for.

“People need encouragement for their efforts, they need rewards, or else they will not try to perform at their best. In all areas of life, school, hobbies and sports, to stimulate progress, teachers and trainers have set up levels where participants can be rewarded for their intermediate success, so they get confidence and start tackling the NEXT step. Without those rewards, few would consider entering many activities. And all those rewards need to be is REALISTIC to be effective.” -Alexandra Kosteniuk, “Abolish Women’s Titles? Ridiculous!”

I agree that titles signifying intermediate progress can be motivating, but why do the titles have to be gendered? Why not add more general titles instead, such as a FIDE Expert title for a 2000 rating? There are many male chess players I know that, especially if they didn’t get a head start by competing at a young age, are likely out of range for the current FIDE titles (unless they begin to study and compete very heavily for many years). Why not create titles that these players can earn too? Gaining 200 rating points in any rating class usually requires at least some, if not a lot of, dedication and hard work, and is certainly an achievement worth celebrating. In fact, the WCM title could simply be converted into a FIDE expert title, open to all. That way, all the players with a WCM could maintain an earned FIDE title, but it would drop the gendered implications. While I see no problem with rewarding more steps along the way to higher titles, I believe that gendering the titles and the mentality of lower expectations for women behind them represent the main barrier in chess for female players.

My Own Point of View

For me personally, the existence of women’s titles has been discouraging from the moment I learned about them. They are a reminder that we live in a world that tries to gender everything---even when you’re a 10-year-old kid that just wants to be good at a board game. I’ve been eligible for the Woman FIDE Master title for years. As much as I'd love to someday earn the general FM title, I will never apply for WFM. This is all I can think about when I consider the meaning of the WFM title:

FIDE Master = 2300

Woman FIDE Master = 2100

Woman = -200

I can’t understand accepting titles that equate the word “woman” with “200 rating points lower”. This can’t be the message we want to send to the world about women chessplayers or female potential in general. I’ve always loved playing chess. I love solving a creative puzzle. I love sitting at the board fighting with all my might to put my will on the board instead of my opponent’s. But, whenever I think about the community’s mentality on gender and chess, it’s disheartening. I feel highly conflicted that I participate in a mental sport where many from each gender encourage a lower standard of achievement for women.

“If they would have a higher goal, they would also reach higher." -Judit Polgar on women in chess, “A Gender Divide in the Ultimate Sport of the Mind”

Sending a message of female limitation, even unintentionally, to current and future female players is dangerous. This negative outweighs any arguable benefits that come from the titles.

“If somewhere back in the recesses of your brain you believe that girls aren’t naturally gifted at chess, then working to improve at the game would be an exercise in futility.” -Hana Schank, “Where's Bobbi Fischer?”

For true improvement in the gender gap, I think there’s much more to it than just using incentives to raise participation rates. I think we, as a community, need to objectively evaluate which incentives are truly beneficial and which are double-edged swords that create more problems than they solve---especially the ones that inadvertently encourage a mentality of lower standards for female players.

“Rather than lowering the bar so that more women earn a master-level title, we should work to eliminate those barriers that are making it objectively more difficult for them in the first place.” -Mary Brock,“Gender Inequality in Chess”

We need work to make it clear to female players that they can and that they deserve to reach whatever level they seek, if they’re willing to put in the hard work.

"I just don't see the point in having these separate women's titles. I'm not sure what they indicate. Women can play with men — they do play with men now. They can earn the same titles as men." -GM Irina Krush,“A Gender Divide in the Ultimate Sport of the Mind”

I think encouraging all female players to work to reach levels universally respected in the chess world would be a huge step in that direction.

“Finally, the girls themselves should know that they are equal to men in terms of chess talents, play in men’s tournaments, study hard and believe in their powers. If most women start acting that way, then one day quantity will lead to quality, and the world chess elite will be enjoying more female players. It’s essential to remember that the sky is the limit, and all the obstacles are in our heads…” -Natalia Pogonina, “Women and Men in Chess: Smashing the Stereotypes”

Prodigy Carissa Yip reached US Chess expert level at age 9 and earned the National Master title at age 11. Photo: Spectrum Studios

Prodigy Carissa Yip reached US Chess expert level at age 9 and earned the National Master title at age 11. Photo: Spectrum StudiosIn the U.S., the rank of expert (the unofficial title for players with a US Chess rating of 2000+) is within the top 5% of American chessplayers. National Master is among the top 2%. I think these are excellent substitute goals for those within the WCM and WFM range.

“She got Women’s Grandmaster, and she didn’t want that title. She thinks she deserves to get the men’s title—and she is right. She can do it all.” -IM Armen Ambartsoumian about Tatev Abrahamyan, who currently has all three of the norms required for the IM title, “Women’s chess champ Tatev Abrahamyan aims to put men in check”Tatev Abrahamyan at the 2015 U.S. Championships. Photo: Lennart Ootes

The difference is these players will know that they are highly ranked among all chessplayers, not just the female ones. FIDE Master and International Master are great goals for those within the WIM and WGM range. And, if one is really ambitious, why not go for overall GM? Or beyond?

“I want to actually become number one in the world, not just number one in women–-also in the men. I’m going to keep working hard to achieve that goal.” -Akshita GortiAkshita Gorti at the 2016 U.S. Women’s Championship. Photo: Lennart Ootes

.

A World Without Women’s Titles:

How would it work?

“Having a title is beneficial in terms of getting special conditions from organizers, becoming a more recognized coach or author, finding sponsors or receiving stipends from certain institutions, free memberships from top chess websites, etc.” -Natalia Pogonina, “The Coveted Titles”

If women’s titles are eliminated, what would happen to free entries and other financial conditions at tournaments for women chessplayers? I’d love to see higher female representation in chess, but what matters to me is eliminating the barriers that discourage females from playing, rather than aiming to create an artificial 50/50 gender ratio. It’s never felt right to me that, for tournaments that offer free entry to “GMs/WGMs”, women grandmasters can receive free entry while higher rated male International Masters may have to pay full price. Of course, offering free entry to all GMs and all IMs could be too many free entries for some tournaments. A possible compromise that would limit free entries and encourage more gender diversity is offering free entry to an unlimited number of GMs, but only a set number of IMs of each gender (on a first to register basis). This would raise the standard overall, encourage top female players to participate, eliminate the need for women’s titles, and make the requirements more fair.

What would it be like?

Recently, the first gender-neutral acting prize in awards-show history was awarded to Emma Watson for her performance as Belle in Beauty and the Beast. Here’s what she had to say about it:

“The first acting award in history that doesn't separate nominees based on their sex says something about how we perceive the human experience. MTV's move to create a genderless award for acting will mean something different to everyone. But to me, it indicates that acting is about the ability to put yourself in someone else's shoes. And that doesn't need to be separated into two different categories. I think I am being given this award because of who Belle is and what she represents. The villagers in our fairy tale wanted to make Belle believe that the world is smaller than the way she saw it, with fewer opportunities for her—that her curiosity and passion for knowledge and her desire for more in life were grounds for alienation. I loved playing someone who didn't listen to any of that.” -Emma Watson’s acceptance speech

While acting and chess are, of course, very different skills. What Watson said about the villagers wanting her character, Belle, to believe that the world held “fewer opportunities for her” is a parallel for the chess world in its current state---it’s not uncommon for prominent figures in the chess world to assert that women have less potential. It’s about time that we put an end to this. Taking steps to eliminate women’s titles and the lower standards they come with---to say, we can do better than this!---would be huge progress towards this.

The Future:

What’s Next?

“There is no person living who isn’t capable of doing more than he thinks he can do.” -Henry Ford

While I’m not sure if women’s titles as a whole will be eliminated by FIDE in the near future, there is a lot that individuals in the chess community can do to encourage higher standards for female players, especially parents, teachers, journalists, tournament organizers, and the players themselves. If you’re in any of these positions in the chess community, I hope you’ll give the following suggestions some consideration:

1. Up-and-coming female players can aim higher for the overall titles.

“You have to put your goals as high as possible and only then will you improve.” -Judit Polgar, “Top female chess player aiming to inspire”

.

2. Chess parents of both girls and boys can make it clear that either gender can achieve any goal in chess, if they’re willing to earn it with determination and effort.

A great example is Carissa Yip’s father, Percy Yip, who admitted that he initially had some “misconceptions” about girls and chess:

“There’s a culture that parents should take girls to dancing class, not to chess. When she said she wanted to play chess, I said, ‘No, no, it’s not easy; you probably won’t like it.’” -Percy Yip, ”Four Young Chess Masters Tackle a Persistent Puzzle: The Gender Gap”

When he realized that Carissa was, in fact, very interested in the game, he became hugely supportive of his daughter and played a large role in her reaching the National Master title at the age of 11, a rare feat for any player:

“Dad is very good in data analysis. He is a math genius. He analyzed my games and results. He found out my weakness (but I am not going to disclose the secret!). We came out with a new plan to reach master by the end of March. We started playing ‘guess the moves’ over the Internet. He showed a position in his computer and the game appear in mine. I had to analyze and find the correct move. He used a lot of fun methods in our studies. I recorded my video analyzing grandmaster games. It was fun studying with my best coach---but also my lowest-rated coach.” -Carissa Yip, “Yip, Yip, Hooray!”, Chess Life Magazine - August 2015

.

3. Teachers can actively keep in mind that interest and work ethic, not gender, are the most important markers of potential.

I think that, because we see so many more male top players, chess talent in females can often be overlooked.

“I think that there's definitely some cultural/sociological bias at work that has made it more difficult for women to excel in chess. I realized a few years ago (after it was pointed out to me by an ex-girlfriend) that I was taking a much more active role in my nephew’s chess education than I was with my niece despite the fact that she was more eager to play/learn and seemed to take to the game much quicker. I had subconsciously not taken her interest in chess seriously and was mortified when I realized I was helping to perpetuate the myth that boys are better chess players.” -Roy Gates, “Women and Men in Chess: Smashing the Stereotypes”

As a chess teacher myself, I think it’s important for coaches to notice which students, whether female or male, have an especially high interest and work ethic and make sure that they have the resources necessary to reach any skill level they seek.

“Once you start teaching a girl how to play, and you see that she has talent, all of this statistical nonsense becomes irrelevant.” -Greg Shahade,“Women in Chess”

.

4. Chess writers can emphasize female players’ overall achievements and place less emphasis on women’s titles.

“Eventually, reporting of events in which she [Judit Polgar] competed stopped referring to her as a woman player and simply referred to her as a player.” -Dan Lucas, Chess Life Magazine Editor

.

5. Tournament organizers can encourage female participation in new ways, prioritizing overall measures of accomplishment, such as general titles or a chosen rating mark, instead of women-only titles.

“These rights I consider to be human rights, but I am one of the lucky ones. My life is a sheer privilege because my parents didn’t love me less because I was born a daughter. My school did not limit me because I was a girl. My mentors didn’t assume I would go less far because I might give birth to a child one day. These influencers were the gender equality ambassadors that made me who I am today.” -Emma Watson, “Gender equality is your issue too”, at the United Nations Headquarters in 2014

What are your thoughts on women's chess titles? Share your opinion on Twitter: #WomensChessTitles https://twitter.com/USChess/status/867789224388554752

About the Author

Vanessa West is a regular writer and digital assistant for US Chess News. She won the 2017 Chess Journalist of the Year award. Follow her on Twitter: @Vanessa__West

Vanessa West is a regular writer and digital assistant for US Chess News. She won the 2017 Chess Journalist of the Year award. Follow her on Twitter: @Vanessa__West

Categories

Archives

- December 2025 (20)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)