In her coverage of the First Annual HBCU Classic, a recurring theme in Melinda Matthews’ interviews was a sense that this event was (and should be) just the beginning of broader initiatives aimed at improving chess’s inclusivity and reach.

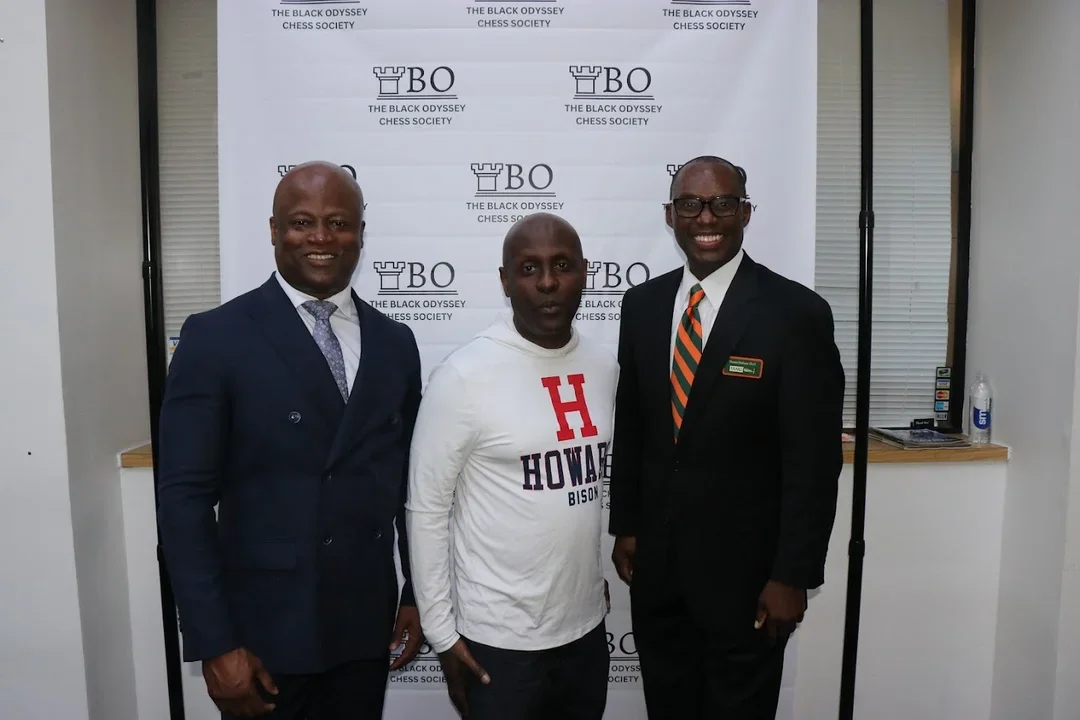

Alan Cowan and Shaniah Francis founded The Black Odyssey (TBO) — the organization that put on the HBCU Classic — in order to “push Black students to be better critical thinkers through chess,” as Cowan explained it, but also to “serve as a bridge between HBCUs … so that these [chess] clubs are no longer clubs, but rather organizations, and they have that structure.” Cowan and Francis both emphasized that they view the potential impact of chess as going well beyond over-the-board competition.

Francis also noted that she wants “to see more thinkers and problem solvers [from the Black community] actually entering the world of chess … not just leaving it to males, but more Black women should come into these spaces.”

There is significant value in increasing chess’s inclusivity not just for the new chess players brought into the fold, but also for existing players who can benefit from being a part of a growing and more diverse community. As Francis notes, “We’re just as important and we produce great thinkers as well, so I wish the community would just see that.”

When it comes to what these initiatives to broaden chess’s reach look like, and how they can continue to grow and evolve, it is important to center the voices of those who are doing the work and reflecting on these questions. Below we have published the transcripts (edited for clarity) from Matthews’ interviews with GM Maurice Ashley (who joined Cowan and Francis to organize the HBCU Classic) and Malik Castro-DeVarona (the tournament champion).

GM Maurice Ashley

Matthews: I know you spoke to us earlier, but can you tell me how you feel now that you're here, what you're thinking about the tournament, and what you're thinking about for future tournaments?

Ashley: It is incredibly moving to see a vision come to life. I am a big idea person and big ideas thrill me. They keep me moving, they energize me. This is a big idea that has finally come to fruition.

Matthews: It actually came rather quickly into fruition.

Ashley: We pulled it together on shoestrings in a day and a half — at least, it felt like it. I felt like, here was the idea, and we didn't want them [co-founders Alan Cowan and Shaniah Francis] to graduate college, these two, without having executed this idea. I told them this all the way back in the fall, but it wasn't until they had gone through a semester of having chess lessons and the like, that they felt confident enough to try to pull it together. So, when they told me this in February, I'm thinking it's kind of quick, but it also was a smaller iteration. It was going to be four schools and it was a local thing.

But it quickly mushroomed into a bigger vision when other people started hearing about it. And that excitement carried us along, even though my organizer had said no, it usually takes a while to do a tournament. But we thought if we can get the schools to buy in very quickly, then it can be less of a “website published” kind of event and more of “those in the know” type of event. The schools would know what we're doing — they just needed show up. And it would be great. Of course, you have to have some rules in place and the like. So, we worked that out as we went along. And I had to give them the details behind chess tournaments and what it takes from an official standpoint. If you're going to have a trophy, people are going to complain if the rules aren't proper and this and that.

We just developed that as we went along. But I knew the students believed in the spirit of the event. I personally called schools like Howard and Hampton and North Carolina. And I said, “This is Grandmaster Ashley here, you've got to be here.” That seemed to have a good effect. Then others bought in and just wanted to be here. It's been an absolutely wonderful journey. It's been trying at times, especially when we weren't sure where we were going to host it. That really came together at the last minute, thank goodness, thanks to Dr. James [Dr. Kevin James, president of Morris Brown College]. When he heard about it, he said, “This sounds like a lovely idea. I want to do it.”

That made it happen because until then, we were suffering. I was basically announcing an event was going to happen without a location, which is kind of flying by the seat of your pants.

Matthews: You were just going to manifest it!

Ashley: Manifested. That's exactly what happened. And if you notice in my interviews, I never said Morris Brown. I always said Atlanta. That’s because we were on the cusp of another location that I just knew was going to happen. But I was afraid to go on the air and say anything about it because we didn't have the place locked down, even though it looked like we were going to. And then that place fell through — after I'd already interviewed with you and the whole country! But thankfully just a few days later Dr. James said yes. And the rest is history. The schedule came out, everything just fell into place. We would not have been able to do this if I hadn't organized big events before. And I'm not an organizer, but I did Millionaires, so I knew exactly the details we had to target quickly, and I knew the rules issues, and I knew what a tournament looks like. And if you're going to do a big tournament, there's certain details that are not that big, but it’s nice to add a few touches, like providing lunch.

Matthews: It's running really well too.

Ashley: We had a hiccup up at the beginning, as chess tournaments tend to do. But part of that, too, was the number of people who dropped out. That caused issues because we had done the pairings already and we had to re-pair.

But after the first round, it's been regular. And I've seen that happen in many, many tournaments. And perfection is not what we aim for anyway. The spirit of this is just so wonderfully powerful. It's the beginning of something — though I like not to think too far ahead — I know the future is coming and I know that there are many other possibilities associated with this. But first and foremost, we had to be successful with the first one. Get it done. Right after that you get your pictures, you get your photo ops, you get your video images, and all that. Once you have all that in place, then you have something to work with to show what could be done and actually has been done. And then you just parlay that into infinite possibilities.

Matthews: Do you want to do this again next year? Do you want to make it an annual event or do you anticipate a different iteration going forward?

Ashley: This particular event will probably be annual, but more schools will be involved, which is the intent. As we're talking now, we have nine schools here.

But if this mushrooms, we could be a victim of our own success. Let's say you go from nine to 50 [schools]. Then you can't have it here, this would be too small. What would you do then? And how would you do it? Would we do a big tournament and, like the Pan Ams, have a final four here, or final six here, final eight, elite eight?

Or if you have regionals, then that has to be organized. And how do you do that properly? So that's why I'm not thinking about the future too much. I do know that we want to have some sort of event next year to follow up behind this, and those plans will be put in place after this is over.

Matthews: Well, I think it's been very successful. Is the goal to always keep this separate or do you want to integrate with the Pan Ams at some point?

Ashley: I think the Pan Ams and the HBCUs can have their own identities.

Matthews: Do you want more representation at the Pan Ams eventually?

Ashley: Absolutely, yes. Absolutely. And those teams will have their own aspirations. There are budgetary concerns. They'll certainly put money aside to be part of HBCU events. Then they'll say, “Well, there's also the Pan Ams.” And we highly encourage that. We’ll get more representation, more faces at that event. I suspect just by the vibe and the buzz here that a lot of schools would've been interested in coming to this if they could have pulled it together. The interest is there; it was just too last minute.

The issue was the two months’ lead time, with no money in their budgets. Those were the two things: you had to know about it and you had to have money in your budget. Howard wasn't going to come because the money wasn't there. Once we said we would help sponsor them, the money suddenly showed up for not just the five we would sponsor, but for 15! And then we didn't have to sponsor them at all. Because no school wants to say another school sponsored their kids when they could have done it. And now somebody's going to take home the team trophy, somebody's going to brag that they're the top HBCU chess team in the country — and some presidents are going to go, “Why aren't we?” So we're expecting school pride, a little bit of jealousy, to take hold and we'll build it from there.

Matthews: And do you also see this integrating with bringing more diversity into the chess community in general?

Ashley: We know there's been a real groundswell of programs all over the country where African American kids are playing chess. You can go to New York, Detroit, St. Louis, you can go to L.A. — it's all over the country. These programs, they're starting to flourish. They're actually flourishing and they've been in place for a long time. L.A. is 17 years. Detroit is celebrating their 20th year.

In New York, the Chess-In-Schools program has gone on for 37 years. These are all an existing base. But those children have not been supported at the high school level and into the collegiate ranks. We know that there are scholarships to places like Webster, SLU, Mizzou, UTD, UMBC, right? We know that they exist, but those scholarships are not going to our kids. No. So if we can start arguing for scholarships to HBCUs — chess scholarships — then maybe some of our chess kids will continue into the collegiate ranks. Yes. Get scholarships and get the support to be able to play in the general population. So that is an important initiative and it's part of the plan moving forward.

Matthews: Is there anything that you think US Chess could be doing differently or better?

Ashley: I think this is going to be a case of following the leader. I mean, US Chess obviously is the top institution in the country and could always do more. I'm positive that's a discussion we're going to have to have.

Matthews: I would love to have that discussion.

Ashley: I mean it's US Chess, so clearly, you have all the networks, you are the leading organization in the country, but somehow it's just not happening. And I don't know why. We've been able to do more with women and girls, but the rest of diverse populations — well, I feel like it hasn't changed much over time. First of all, who's on the [Executive Board] matters. Yes. Who's on the board? Who's in charge? Who thinks it's important, who's advocating and pushing for it? I think that matters. And if you're not in the community and aware of some of the challenges and aware of the things that motivate the community, give it pride, then you might just end up paying lip service and not know what to do.

Matthews: That’s it. Even coming to this tournament, I feel like there's a different vibe from most.

Ashley: Absolutely. And it's just — I think US Chess doesn't know how to capture that vibe yet. And it matters. I think people generalize when they think of chess and the people who are excited by it. They don’t understand that certain approaches affect certain communities. And if you don't know those touchpoints and the icons that matter in the community, the kinds of issues that matter, the ways of expressing it, why it is that this is such an emotionally resonating moment, then you don't know what you don't know. And so I think that that is a natural ignorance. It's not anybody's fault, it's just not.

Matthews: I know we're talking about forming a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion committee, but it seems like we need to know which resources to access so people like you can help us navigate correctly. And I'm getting way off track; I didn't intend to go this far. But this really means a lot to me. I want to see us be more involved and more inclusive.

Ashley: No, I think it's an important point. So here's the thing. If you talk to people who are working on the ground — we've got Detroit City Chess club over there — you won't go to them and talk about diversity and inclusion and equity because they don't need to know. Think about it that way. You're going to form a committee and we're like, “What committee? What are you talking about? We're just working on our kids. We're just going to be on the ground and get it done.” So I think that's where you've already got a couple of barriers.

Matthews: Too much bureaucracy.

Ashley: By the time you get to the people, we’re like, “We've trained 200, 300 kids already and they're going off doing their thing.” So when I hear that [committee] discussion now I do get a little tired. You can go talk about your committee and what you might do and the meetings you'll have and the votes you'll need, but in the meantime, folks are just doing it. So I think the folks who are doing it need support and you need to step back and let them take charge. They're reputable organizations who've been around for a long time. Let them take charge. What are their ideas? How do you find support for their ideas and committees? Whatever it takes — get it done. There are enough organizations that have track records in place for decades who can’t get support. And I think US Chess should be seeking them out like a heat-seeking missile and say, “Okay, we need to support this organization. They’ve been around for 20 years and have coached thousands of kids and these kids are now in universities and showing the effects of being chess players.” You have all these amazing stories. They're astonishing and you're missing all of them. They're not being showcased. What does chess do for African American kids? Hey, guess what? In only one city — I keep bringing up Detroit ‘cause they're in the room — they have literally hundreds of kids who are off to college and they're assuring your success stories. How come they're not being showcased?

Matthews: We actually just started doing these kinds of interviews. We want to showcase people who have learned or grown from chess but they're not necessary a grandmaster or an IM.

Ashley: And those are better stories. They're much better stories.

Matthews: I know it's just a microcosm because I've only talked to four people here so far, but what’s interesting is that they all started playing when they were older. It's because something sparked in them despite their obstacles. And it's real, it feels honest.

Ashley: Incredible. I've had students — like Francis Day, one of eight kids from Nigeria who came to Harlem to live with his family. He was a part of our chess team — was not one of the best players on the team, but part of the top eight. Francis now is the chief financial officer of a hedge fund. So you know what he's making, right? He’s doing okay.

We talked recently and Francis said, “You don't know how much chess did for me. I think like a chess player.” So this guy's making beaucoup dollars because chess impacted his life as a 12 year old. And he gives credit to that.

And that's just one small experience. I've been around long enough to see this long-term impact. But there are other stories and all these kids who are ignited by chess, who are fired up by chess. They don't become IMs, they don't become GMs. And most of those are not big stories, frankly.

Matthews: Like I said, the stories here have been different from those I usually hear, especially the starting age.

Ashley: I'm a grandmaster and I started at 14. That's a crazy chess story. Nobody starts that late and gets a grandmaster title. So you’re right. You'll find every bit of unusual stories here.

Matthews: Beautiful. I love it. I love it.

Ashley: And a lot of times when the stories are told, your typical audience will say, “So what's their rating?” We don't care here. We see you're passionate. We ask, “What school do you go to, what are you planning to do with your lives?”

Matthews: So it's more a part of life, it's a part of what you do, who you are…

Ashley: … and you love it. That's what we’re all about. And soon we're going to be able to say, “Oh, that kid came to Morehouse because he got a chess scholarship.”

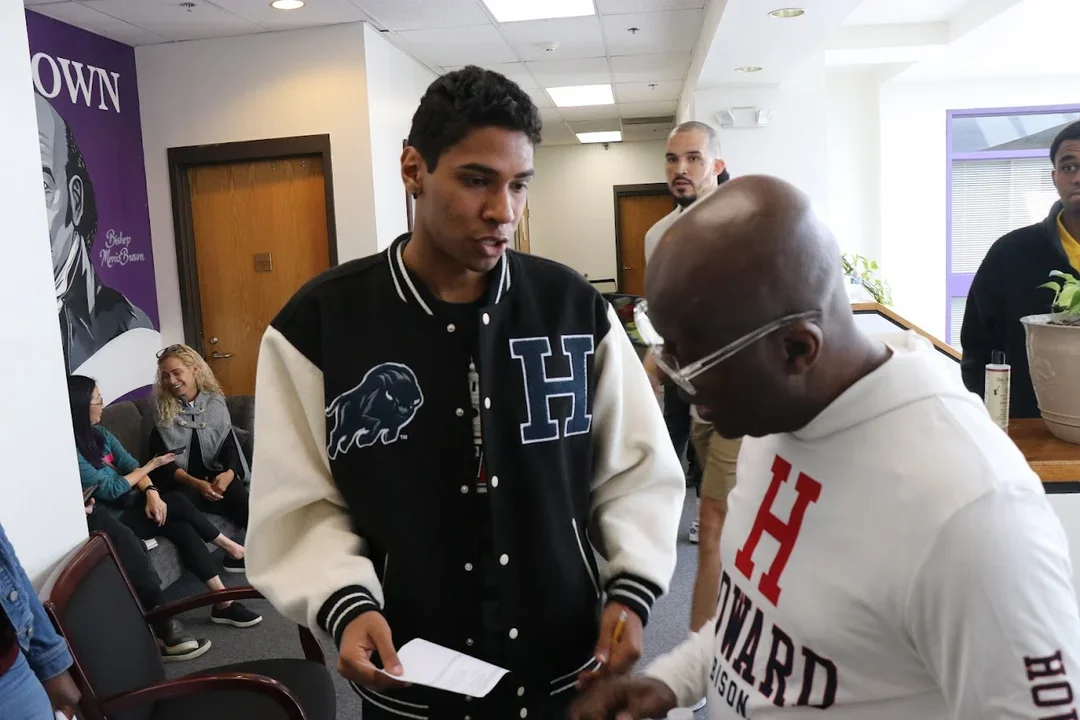

Malik Castro-DeVarona

Matthews: Congratulations. First of all, how do you feel?

Castro-DeVarona: I feel good. For me, the whole tournament was a big culminating experience because I put a lot of time into my chess. And, so, seeing myself improve, particularly this year and then — I've been in a lot of tournaments and I've placed, but I haven't won before, so yeah, it feels good.

Matthews: When did you start playing chess? Was it when you came to Howard or is it before that?

Castro-DeVarona: I started learning when I was really little. I won my first chess tournament in kindergarten, and I played first through fifth grade. After that, there weren't any after-school chess programs in my school, so I didn't pick back up until college.

Matthews: So it sounds like you played through your school programs?

Castro-DeVarona: Yeah, after-school programs.

Matthews: Did you participate in any local tournaments or were these mostly school tournaments?

Castro-DeVarona: No, I would go to local tournaments and state tournaments from first to fifth grade. After that, not so much. I mostly spent my middle school and high school playing sports.

Matthews: Where did you grow up?

Castro-DeVarona: I'm from Los Angeles. Yeah, I’m born and raised in L.A.

Matthews: So you traveled across the country to come to Howard?

Castro-DeVarona: Yeah.

Matthews: What year are you in?

Castro-DeVarona: I’m a sophomore.

Matthews: So you can play in a couple more of these tournaments then.

Castro-DeVarona: Fingers crossed. Yeah.

Matthews: Did you go to the Pan Ams this year?

Castro-DeVarona: I did. That was another really big moment.

Matthews: How was that experience for you? Was that your first intercollegiate tournament?

Castro-DeVarona: It was my second. When I came into Howard as a freshman last year, I went to the Pan Ams and that was my first real taste of the intercollegiate experience. And it was good. We didn't perform well — we sent two teams, an A and B team, and our A team placed 52nd out of 57 teams. But I really had a good time. I got the chance to play my first grandmaster ever. So it was great. It lit a fire in my belly to practice and improve my chess for the next year. And our team did amazing. We got eighth place this year.

Matthews: That's amazing.

Castro-DeVarona: Couldn't be prouder of everyone.

Matthews: So how did you find chess at Howard? Did you come to the school planning to be on the chess team?

Castro-DeVarona: Not initially. For context: the reason I wanted to go to Howard in the first place is that I grew up in a Hispanic household in a white neighborhood. My family's Hispanic; they're from Costa Rica and Cuba, respectively. So I didn't grow up around a lot of Black culture. And also I'm a poli-sci major, so putting D.C. politics and the HBCU community together — that's what made me come here in the first place. I did not come here initially playing planning to play chess. I also happen to be a first gen [first generation college student] so my family doesn't have experience in college. So we didn't think about [me playing sports in college] even though I played sports my whole life — I did soccer for 14 years. I didn't want to pursue it in college. So right around my senior year in high school, I stopped playing soccer and it was like, “Okay, I have all this free time. Now what do I want to do with it?” I was like, “Well, I've always loved chess. Let me get back into it a little bit.” And then before I got into Howard, before I knew I was going to Howard, before we flew here, I messaged the club on their Instagram. I was like, “Hey, are you guys active?” And they were like, “Yeah, stop by our meetings.” And ever since then I've been here.

Matthews: So that's interesting that you chose an HBCU even though you're not Black.

Castro-DeVarona: I guess I should provide a little more context. I have two mothers. One is Costa Rican, one is Cuban. I have a younger sister who's 17. One of my parents carried me and the other mother carried my younger sister and they used the same Black donor.

Matthews: That's interesting. But you were raised in a white community. You sound like me. I was raised in a white community too, so I kind of know how that feels. So did you always know that you were going to go to an HBCU?

Castro-DeVarona: No, I never even started looking at or learning about HBCUs until my junior year [of high school]. My junior year was when some mentors said, “You should really consider some of these options.” And the more we looked at it, the more it seemed like it would be the place where I would grow the most as a person.

Matthews: Have you found that to be true? Have you enjoyed the experience?

Castro-DeVarona: One hundred percent, without a doubt. My favorite part of being here is my peers. I'm surrounded by amazing people and experiencing things I think I would not have anywhere else. So yeah, I'm very grateful to be here.

Matthews: And you're pretty active now in the chess club. Does the chess club have a structure, like president, vice president, etc.? And are you an officer in the club?

Castro-DeVarona: Yeah. I'm the current president of the club. I was elected last year and I took office at the beginning of this year. This year we had a really small team. That's partly because the chess club was only revived three years ago, this being the third year. It had gone through periods of being active, but people graduated, it died away. And so we only had myself, a vice president — who also happens to be my best friend here — and a social media coordinator. So it was a small team. We've expanded for this coming year to eight positions, so it should be a lot more fleshed out.

Matthews: What do you envision for the Howard team in general? Where do you envision it going or becoming?

Castro-DeVarona: As I've had the opportunity to work with the club, I've come to appreciate more things about it that I didn't initially. So first and foremost — even before I took office — once I went to the Pan Ams, I saw how competitive and how amazing chess cultures are at other colleges, but HBCUs aren't a part of that culture. We were the only HBCU competing. As one of the few teams with Black people on it in general, it made me feel like we needed to join that space and there was no better time to do it than now. So that's my main mission. My main mission is to make sure that by the time I graduate, we have students on scholarship just like the other top schools have, because that's what it takes to be able to have competitive players and to give them the time and the resources to be competitive. By making that happen, we're also creating a pipeline for people of color to be able to play competitive chess in an HBCU environment. It’s not an opportunity that exists yet, but it should. And so that's what we're doing, definitely. But along the way, what I've also come to learn — and it was another good chance to see it here at the HBCU Classic — is a lot of our target audience is amateurs or people who are just getting into the world of chess.

Matthews: Right. I'm surprised how many beginners or novices are at this tournament, but it's in a good way.

Castro-DeVarona: Absolutely. But it definitely helped underscore the point that we need to — it's incredibly important to — focus on this competitive side of the chess world and make sure that we're slowly coming into it. We need to be able to have a space for people just getting into chess and people who are still relatively new because that's most of us.

Matthews: Do you have some sort of outreach program? Do you work with people who want to learn or are you in the schools?

Castro-DeVarona: Within the club we give lessons and outside, we work with some high schools. We work with a detention center. We're going to be working with the police shortly. So we have outreach, but it's mostly through just our own context and reaching out. Next year we're going to be focusing a lot more heavily on that side of things.

Matthews: And how are you finding funding and resources? Has that been a challenge? What do you have in place to bring in coaches and things like that?

Castro-DeVarona: It's been an obstacle, but it's been one that we've been fortunate enough to overcome this year and the year prior. If you have a club here at Howard, you're able to apply for funding each semester. So we were fortunate enough to get around $9,000 each semester to be able to put towards our club, to fund flying everyone out to these tournaments, and whatnot. But to attend the Pan Ams, we had to raise around $8,000, which we managed to pull off after making it on the front page of The Washington Post after putting on an event with giant glow-in-the-dark chess pieces. The pieces are still in my room ‘cause we don't have anywhere else to put them. (swings camera around to show them) But yeah, it was really fortunate that was able to get us there. Fortunately, we've been able to fundraise one way or another.

Matthews: Can you tell me a little bit about getting to this tournament? I know that it was touch-and-go for a while.

Castro-DeVarona: Leading up to it, because the invitation was a little short notice, it was definitely a scramble to make sure we got the funds. The school helped us out a lot, and to make the last little bit of ends meet, we were doing fundraising, like hosting bake sales and going into the city. So it worked out. Ultimately, a really nice part of the process was that we wanted to send three teams this time and we were able to send an all-male team, an all-female team, and an open gender team.

Matthews: So that was deliberate? Because I was really impressed that there were two female teams there [Howard C and Spelman]. Proportionately, that's a big deal.

Castro-DeVarona: Our campus is 72% women, so we want the club to reflect that, and we also want to be as inclusive as possible. So yeah, I was really happy that we were able to afford that.

Matthews: That's wonderful because it's not just race representation, it's also gender representation. And there are not enough women in chess, especially not enough women of color. And so what do you foresee as the future of chess for the Black community? Where do you see it going or what is your vision for the future?

Castro-DeVarona: My vision for the future is, well — even though I say that this [the tournament] feels like the start of everything, it's still hard to picture. Even last year, the president before me was trying to reach out to all these HBCUs and identify where the clubs were. It was hard and we weren't able to find many people. So just being able to see everyone at this HBCU tournament — it was really impactful. And now that we know, it's like discovering that we all exist. We didn't know going into it that we do. It's a whole network that just got created now.

Matthews: And how do you keep the momentum going? I know Facebook isn't popular among young people anymore, but will there be some sort of groups like that where you can stay in touch with each other?

Castro-DeVarona: Absolutely. We’ll be digitally doing work together, I'm sure. I think an optimal future would be having multiple tournaments throughout the year that we can all look forward to and aim toward, collaborate on, and make sure we're working together online. In this next couple years, this will be an opportunity for every HBCU in attendance and even for HBCUs that want to start or grow their chess programs to make sure that we're all uplifting each other to ultimately be as competitive as any other college.

Matthews: Jamaal [Abdul-Alim] mentioned you're a Chess.com ambassador and I actually don't know what that means, so do you want to tell me about that?

Castro-DeVarona: Sure. Chess.com has an ambassador program where you can register a few ambassadors from your chess club if you're a college chess club. Basically, it allows you to work and participate in some Chess.com events. They'll send you little care packages with merch and whatnot. Sometimes it's water bottles or beanies or hats or little trinkets. And then they let us participate in bimonthly competitions with small prizes here and there. And it's nice. It's a good way to facilitate engagement.

Matthews: Are you a speed chess player or do you prefer the slower classical — or both?

Castro-DeVarona: I am a sucker for slow chess. But when it comes, if you have to play fast, I won't shy away from it.

Matthews: Apparently, you're pretty good at it since you won the playoffs.

Castro-DeVarona: I'm not too shabby. It was fun. I had a really good time. I think it was amazing. I had my own takeaways from it. I was just happy to see everyone and to get to know everyone. But I think, particularly for some of our own players, it was also a big culminating experience. I'll give a quick example. We have some players on our B team who were like 600, 700 rated coming into this school year. And I was putting their games into the computer database. Chess.com has a nice little feature where you can input your game and it'll say, “Oh, you played like a 1500” or “This is the strength you played at.” And they had games where they had played at a 2000 plus score. Even if they didn't necessarily win the game, their evaluations were that they at least played a 2100, like a 2000.

Matthews: That's amazing.

Castro-DeVarona: And it's really nice for them to see how far they've come, that they've really made great strides in their abilities. It's all a very big culminating experience. It feels like everything we're doing is earned and it's showing and everything is growing. I couldn't be happier.

Matthews: It sounds wonderful. And I know you guys brought in a couple of coaches, including Tani [Adewumi].

Castro-DeVarona: Yeah, we had Tani for the Pan Ams.

Matthews: He's awesome.

Castro-DeVarona: Tani was great. We had some super good takeaways from our sessions with him and Jerald Times, who's our main coach, who we flew out for the Pan Ams and who also flew out for this HBCU classic.

Matthews: I know him only by reputation and name, so I had no idea what he looks like or that he was there, so I didn't get to talk to him. I'm really sorry about that.

Castro-DeVarona: Mr. Times is fantastic. He's been really helpful for everyone. And we're super glad to have him on board and hopefully, we'll have a long and fruitful partnership.

Matthews: Awesome. Would you be interested in annotating one or two of your games and sending it to me? One of the ones you're most proud of.

Castro-DeVarona: Sure. My favorite game was round three, where I was playing the president of Hampton, Breon McCray. He played a really good game. He was completely winning at one point. So I was really happy with that game because it was the hardest game for me, and it showed that there's definitely some strong competition out there.

My favorite games of the tournament would have to be the blitz because the three people who got perfect scores in the tournament were myself and my compatriots, Goodness [Atanda] and Samir [Acharya]. It's pretty established that they're the strongest players in the club at Howard. So getting to play them was a real treat and those games stuck out to me the most. Once I get the video for those, I was going to try to annotate and I can send you those if you'd like, or if you prefer one of the games from one through five, I can do that.

In the playoffs, both Samir and Goodness did a fantastic job of putting pressure on me. Samir, who was my round one game, was the harder game because he's the strongest player in the club and he's super gifted. I was never sure how it was going to end. Goodness had to play as White, and he's known as the most rock-solid Black player in our club. He does not lose as Black for the life of him. His Caro-Khan is flawless, but he had White against me, so the onus was on him to put on some pressure. And he happened to go into a line in the Sicilian called the Najdorf Sicilian, which is one of two lines I’d studied. So I had a lot of preparation, and I think that that really helped me in that game. When he went wrong later, even though it was higher-level chess, it wasn't necessarily too difficult on my end because I knew the themes of the position. So it was a little bit easier to navigate, but I was really happy just to get to play it.

A lot of the games were really memorable. In round four, I had to play someone from Spelman who was strong and she ended up beating one of our best team players. So going into the round, I already knew that she was strong, which made that a good fight as well. Overall, I'm very happy. I couldn't be happier with the event and with our teammates and I can't wait for the future.

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (6)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)