Inaugural HBCU Classic Carves a Space For Black Collegiate Chess Community

A Historic Occasion

Chess might be 1,500 years old, but on Saturday, April 22, it felt reborn. The inaugural HBCU Chess Classic, held on the Morris Brown College campus in Atlanta, set a standard on how to reimagine over-the-board chess tournaments in a way that felt modern, fresh, and rife with possibilities.

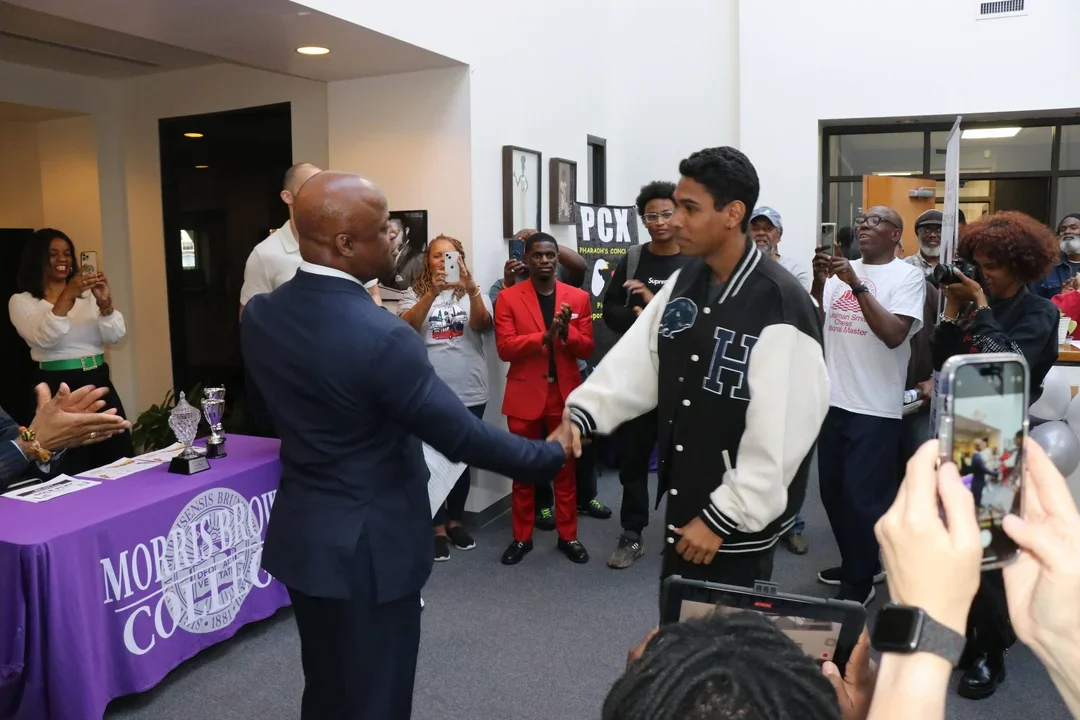

Given the event’s historic significance, perhaps it’s not surprising that the tournament crackled with camaraderie and excitement instead of palpable competitiveness. Grandmaster Maurice Ashley, who had recognized the magnitude of this moment early on, lent his star power to the proceedings, working diligently behind the scenes pre-tournament, and serving as host, cheerleader, and emcee throughout the day. “It’s incredibly moving to see a vision come to life,” he says, clearly emotional. “This is a big idea that has finally come to fruition. We pulled it together on shoestrings in a day and a half — at least it felt like it.”

Local luminaries, the press, and esteemed chess journalists and educators were also in attendance. Atlanta mayor Andre Dickens stopped by during the lunch break to wish the players good luck, mingle with onlookers, and pose for photographs. Dr. Daaim Shabazz, creator of the award-winning blog, The Chess Drum, and Jerald Times, the 2021 Chess Educator of the Year, attended to support the schools, witness history being made, and network. Dr. Kevin James, president of Morris Brown College, circulated around the tournament constantly — he was even spotted playing a few casual games. James deserves a special shout-out for providing the tournament space at the last minute after the original site fell through. The Dr. Gloria L. Anderson Multipurpose Complex, though tightly packed, felt airy and light-filled, its walls warmed by eclectic original African American art that heightened the sense of gravitas, history, and timelessness.

Planning the Event and Its Significance

The seeds for the tournament were sown in September 2022, when Morehouse College senior Alan Cowan and Spelman College senior Shaniah Francis co-founded The Black Odyssey Chess Society (TBO), a 501(c)(3) non-profit with a mission “to construct community and establish a future in which tomorrow’s leaders are encouraged to be critical thinkers in all spaces, with a purpose to serve the greater good.” Organizing an HBCU tournament was part of TBO’s long-range goals, but their plans accelerated once Ashley got involved. “We didn’t want them to graduate college, these two, without having executed this idea,” Ashley says.

Originally, the organizers thought the tournament would be hyper-local. But as word got around, “it quickly mushroomed into a bigger vision.” Working within their short turnaround window, Ashley says the team thought, “If we can get the schools to buy in very quickly, then it can be less of a ‘website published’ kind of event and more of a ‘those in the know’ kind of event.” Their strategy worked: despite looming finals as the spring semester wrapped up, 48 players from nine schools — Fisk University, Florida A&M University, Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, Morris Brown College, North Carolina A&T State University, Spelman College, and Texas Southern University — descended upon Atlanta to compete, some in their first tournament. Still, pulling together the tournament was not easy: “There was a lot of crying, a lot of overnighters, a lot of writing and work, especially when it was only the two of us and Maurice,” Francis admits. “It was really just the three of us doing the background work.”

The U.S. Department of Education defines HBCUs — Historically Black Colleges and Universities — as “…any historically black college or university that was established prior to 1964, whose principal mission was, and is, the education of black Americans, and that is accredited by a nationally recognized accrediting agency or association determined by the Secretary [of Education] to be a reliable authority as to the quality of training offered or is, according to such an agency or association, making reasonable progress toward accreditation.” In contrast, a PWI — Predominantly White Institution — is defined as a university that has 50% or more enrollment from white students, but it is also used to refer to any university that is deemed “historically white.”

Cowan, who has played in collegiate tournaments, says one reason for founding TBO was that he “noticed there’s not a lot of people there who look like me and not any tournaments that are catered towards HBCUs. It’s predominantly the Ivy Leagues, it’s the PWIs. When it comes to Black attendance or attendance of Black universities, we show up in very few numbers.” He and Francis decided to change that by pushing Black students to become better critical thinkers and by serving as a bridge between HBCUs. “All we can do, really, is just push and push and push and make sure that the HBCUs, the Black schools, have the options, they have the funding, they have the resources, so they have the ability to be a part of these spaces,” Cowan says.

The Tournament

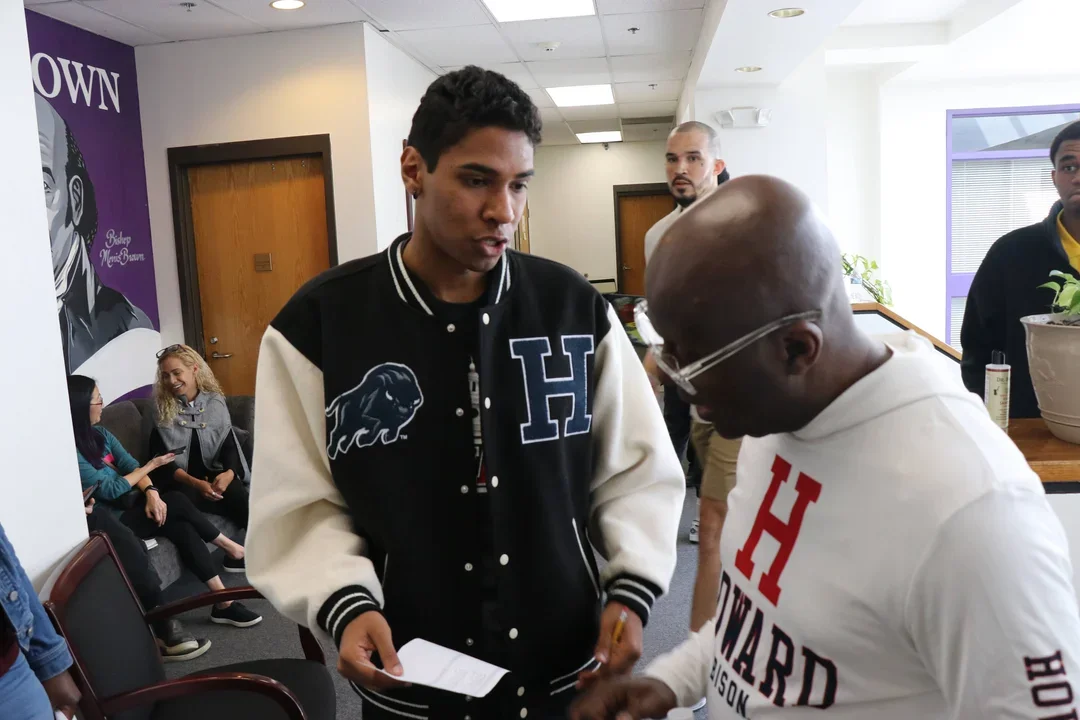

Howard University and Morehouse College, boasting 15 players each, shared the largest overall representation. Howard fielded three teams, with their A team definitely bringing their “A” game to the five-round, G/25+5 event. Howard A took the top three individual spots and the overall team championship. Malik Castro-DeVarona prevailed as the first HBCU Chess Classic individual champion after defeating teammates Samir Acharya and Goodness Atanda, second and third, respectively, in playoffs after all three ended with perfect 5-0 scores.

Howard’s dominance was not altogether unexpected. As the only HBCU team to compete in the Pan American Intercollegiate Team Championship (“Pan Ams”) for the past two years, they’ve received coaching from Jerald Times and prodigy FM Tani Adewumi — both suggested by another HBCU advocate, Jamaal Abdul-Alim. Of special note, too, were the all-female teams — Howard’s C team and Spelman College — who both represented their schools proudly.

Champion Castro-DeVarona, who’s also the president of Howard’s chess club, says he would like HBCUs to participate in more chess tournaments such as this one. Eventually, he’d like to see greater representation at the Pan Ams. “Once I went to the Pan Ams, I saw how competitive and how amazing chess cultures are at other colleges, but HBCUs aren’t a part of that culture. We were the only HBCU competing. As one of the few teams with Black people on it in general, it made me feel like we needed to join that space.” He says his mission is to figure out how to fund chess scholarships at HBCUs so “by the time I graduate, we have students on scholarship just like the other top schools have, because that’s what it takes to be able to have competitive players and to give them the time and the resources to be competitive. By making that happen, we’re also creating a pipeline for people of color to be able to play competitive chess in an HBCU environment.”

Below are Castro-DeVarona's two playoff victories against his teammates. Ashley provides commentary on each game below:

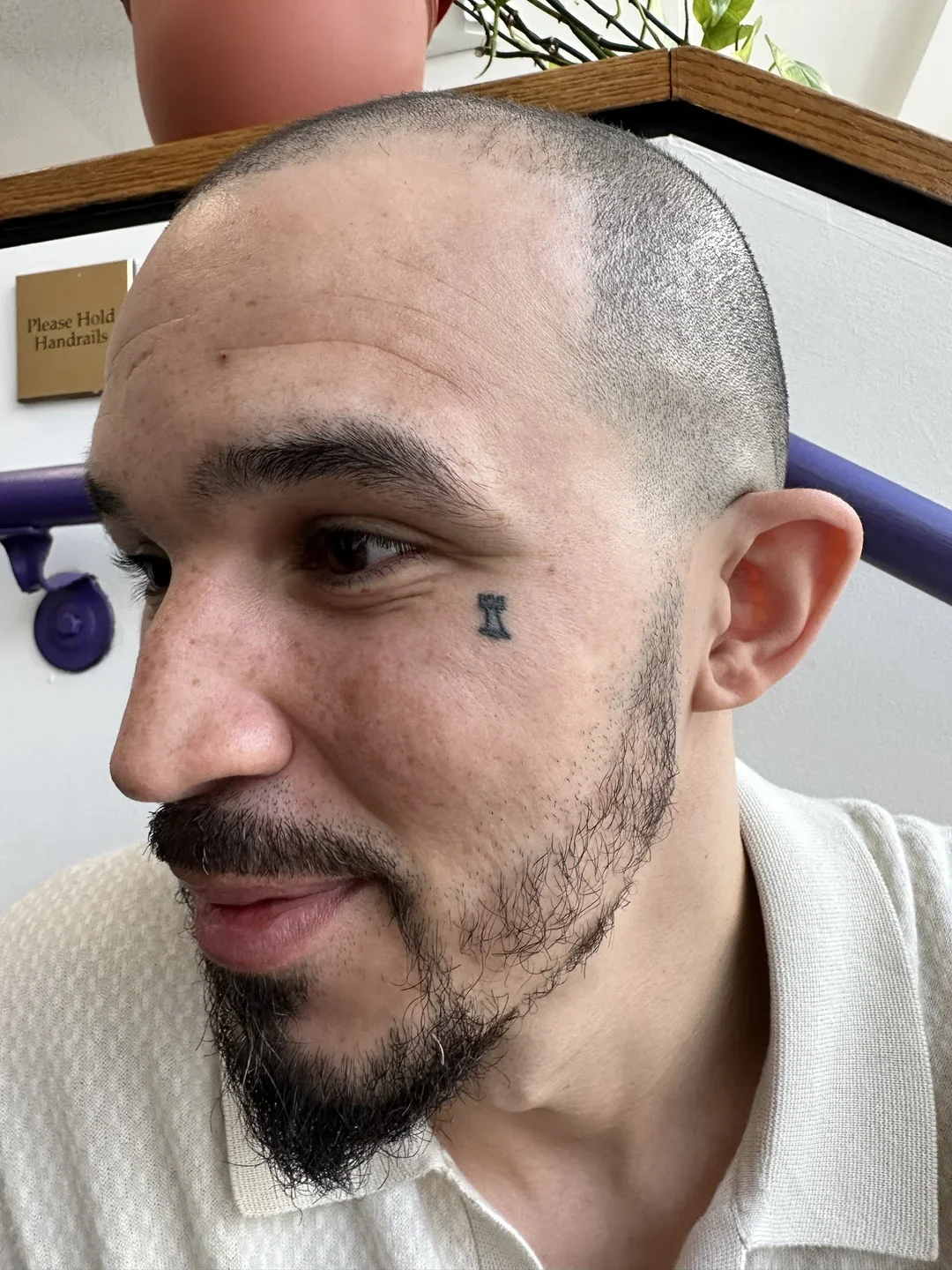

The tournament itself ran with remarkable efficiency. After a brief struggle with WinTD before the first round, which delayed the start by about 10 minutes, the remaining rounds were completed with no notable hitches. The tournament staff even made up the lost 10 minutes — the final round began at 4:30 on the dot. A smooth, drama-free event is any organizer’s dream, but what made its success even more impressive is that this was tournament director Seth Dousman’s first rated tournament! Seth began playing chess seriously during the pandemic, fueled by his interest in a woman who couldn’t stop gushing about “The Queen’s Gambit.” Seth began watching the series to impress her and found himself hooked — not by the woman, but by chess. “She wasn’t the one,” Seth says, “but the chess was. One hundred percent.”

Seth started playing chess on his phone whenever he could, including while at the barber’s. His barber, who also loves chess, was so busy looking over Seth’s shoulder and suggesting moves that Seth became seriously concerned about the state of his style. But this shared interest led Seth to begin hosting a chess meetup at the barber shop. The gatherings have since outgrown the shop, moving to larger venues and expanding into several evenings. Seth became a tournament director after his casual get-togethers morphed into tournaments for “bragging rights and a bar tab.” Seth finally played his first rated tournament in February and plans to continue playing, hosting, and TDing indefinitely. He’s even started working with a coach, national master Deepak Aaron, to improve his game. “I got a rook tattooed on my face,” Seth laughs when asked about his chess future. “I’m a lifer. I love the community.”

The tournament positively hummed with excitement, fellowship, and a spirited vibe not often felt at more jaded, competitive iterations — and it literally hummed, too, thanks to a DJ pumping energetic music between rounds. Welcome touches included a provided lunch — much appreciated by the always-hungry college students who gratefully decimated the wraps, sandwiches, and cookies — and a post-tournament pizza party, complete with said DJ, to close out a successful day.

For those of us used to the hush of traditional tournaments, the overall mood felt less like a battleground and more like a celebration of chess and all its possibilities. “The energy is positive and it’s a lot different,” says Shabazz. “I played in the Pan Ams many, many years ago, and this event, while smaller, has a different energy, there’s a different excitement. There’s also a commonality that students have with each other because the HBCU is a kind of special group, and a lot of the students relate to each other because they go to one of the 107 HBCUs.”

Chess in the Community

Youthful vision, energy, and determination, grounded by strong mentorship from Ashley, were the ingredients that made this tournament a success. And in the end, what this team proved is that the collegiate chess community needs to make room for HBCUs.

The tournament also showcased why traditional chess avenues and the Black community sometimes diverge. My informal and far-from-scientific poll indicated that the Black community’s introduction to chess often manifests itself quite differently from the “My dad taught me to play when I was three and then I started going to tournaments” narrative. Many of the people I spoke with fell in love with chess as pre-teens or older, and usually they were self-motivated. School was not where they learned or played — instead, their chess interests were sparked in local hangouts, in community programs, in the neighborhood, or through the media.

Of his introduction to chess, Shabazz says, “Nobody in my family plays chess. I saw two boys in my neighborhood playing chess, and I was fascinated that they could stay still so long. I wanted to know what this was all about. So I went home and I looked up chess in the encyclopedia and I learned the moves.”

Similarly, Thomas Clem of Metro Atlanta Chess Partners speaks somewhat wistfully of missed opportunities: “I’m self-taught. I’ve been playing chess all my life. I got into rated tournaments about 12 years ago. I was volunteering at a middle school and we were invited to a US Chess rated tournament. I was 40 years of age at that time. And the sad part about it, I never knew how to become a chess professional.”

Those who teach chess in the community tend to integrate it holistically into a larger curriculum that often includes life lessons — the goal is to develop well-rounded community members, not necessarily grandmasters (although that is encouraged, too).

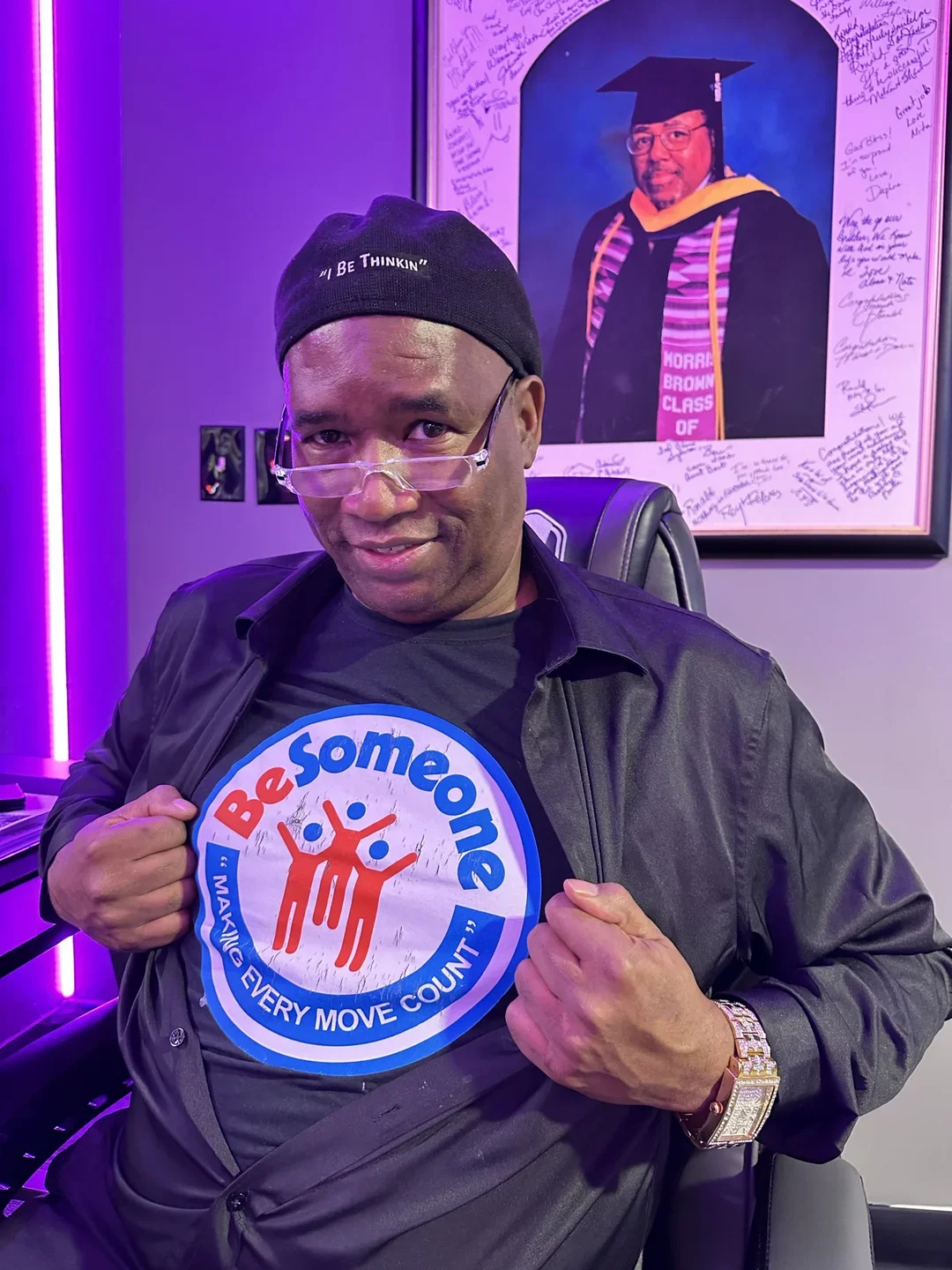

“My method is less about chess. My method is about teaching young people to think things through,” says Orrin Hudson, the colorful founder of Atlanta’s Be Someone Inc. “Get your head up, get your pants up, get your grades up, and the big one: Never give up.”

Ernest Levert, of the Royal Oak Initiative in Columbus, Ohio, echoes this sentiment. The institute, he says, started in 2014 “with the idea of using chess as a mentoring tool for reaching young people.” However, they also focus on “carving out spaces for certain demographics of populations that don’t always find safety in traditional chess spaces. We focus specifically on Black and brown communities, and making space welcoming for women. It’s friendly and it’s fun, and it’s really about connections. It’s about culture, it’s about community.”

Demonstrating how strong and committed the community network is, volunteers from the Detroit City Chess Club (DCCC) came out in force to support TBO’s efforts, despite having no teams in the tournament. Catherine Martinez, who’s been with the club for 20 years and calls herself the club’s “VP” — Volunteer Parent — says, “We have a large legacy community of families, sponsors, and players we’ve built over 20 years. We take pride in working in the Detroit metro area — in underprivileged areas that need critical thinkers.” Martinez says DCCC’s purpose — and reason for appearing at the tournament — is “to elevate the player as a whole. It's not just about championships and trophies, but developing functioning, community-focused, socially responsible citizens.”

Francis would like to see more Black women in tournaments — “And for us to get a Black women grandmaster!” Volunteer Tiffany Harris, an active player from Georgia, agrees. “I love getting more females started in chess. It's good for thinking ahead and making the right decision. And it applies to life as well. How you have your pieces lined up is how you also want to think ahead for your life.” As for the collegiate chess community, Francis says, “I just hope that they understand how valuable HBCUs are compared to PWIs. We’re just as important and we produce great thinkers as well, so I wish the chess community would see that.”

Shabazz notes, “This tournament shows that there are overlooked segments … not just the African American segment, but also the young segment.” But Ashley thinks that those wishing to support the Black chess community should be careful to follow the community’s lead. “I think people tend to generalize when they think of chess and the people who are excited by it,” he says. “They don’t understand that certain approaches affect certain communities. And if you don’t know those touchpoints and the icons that matter in the community, the kinds of issues that matter, the ways of expressing it, why it is that this is such an emotionally resonating moment, then you don’t know what you don’t know.”

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (2)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)