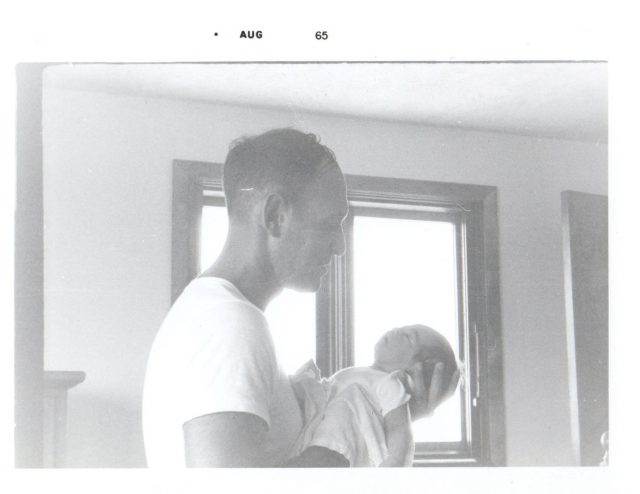

This is my first Father’s Day without a father, as my dad, Wallace M. Rudolph, died on March 18. My sister Sarah wrote my dad’s obituary, describing him as an “eternal optimist.” My dad trusted others completely. His favorite story about when I was a baby sets the framework. My dad, at that time a professor at The University of Nebraska College of Law, was asked to be one of the defense lawyers for Duane Earl Pope, who killed three people and paralyzed a fourth. There was some concern about where to jail Pope. My dad told the court that Pope could stay with him, his wife, and his newborn. The court didn’t allow that housing arrangement. When I was old enough to ask questions, I asked my dad why he offered to house Duane. My dad told me that Duane had been temporarily insane when he killed. My dad was emphasizing the “temporary” part of insanity to the court when he offered our home for Duane. My dad taught me chess when I was five years old. He let me win every game, which I liked. My mom never learned to play chess. She let my dad handle all chess-related arrangements. My dad was not a tournament player and did not know the more esoteric rules of chess such as en passant. When I was nine years old, I asked him to stop letting me win. I was soon able to win against him “for real.” I began attending the Lincoln Chess Club in February of 1975. Eight months after my first tournament, my dad spotted a newspaper article about the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL) chess team winning the 1975 Pan American Intercollegiate Team Championship. UNL’s first board was national master Loren Schmidt. My dad contacted Loren, who started teaching me chess. In under age 13 tournaments, I routinely won the “first place” trophy and my friend Angel Niedfeld won the “first girl” trophy. The boys were shut out, tournament after tournament. The boys’ parents complained. So then the tournament organizers came up with a new structure for the under age 13 trophies: First Overall, First Boy, and First Girl. I was the Nebraska Elementary Co-Champion in 1976. My family moved to Washington State in the summer of 1976, for my dad’s new position as dean of the University of Puget Sound School of Law. My dad located the Tacoma Chess Club and soon I was attending it every week. My dad also found tournaments for me, such as the 1977 Northwest Junior Open (won by John Donaldson, directed by Korneljis “Neil” Dale). I have a photocopy of a letter my dad wrote to Neil Dale: “July 5, 1977 Mr. K. Dale 1201 NE 189th Portland, OR 97230 Dear Mr. Dale: Enclosed is Check No. 406 in the amount of $8.00 entry fee for Alexey Rudolph for the Northwest Junior Open which is to be held on July 9th and 10th. Sincerely yours, Wallace M. Rudolph.”  My dad read my monthly Chess Life & Review magazine before I did, which I found annoying because he would ruin the surprise of what my new rating was. In those old days, you found out your new rating on the mailing label of your magazine. You couldn’t just log into uschess.org to find out your new rating. My dad loved buying technology, starting businesses, and playing tennis. He bought me the Fidelity Chess Challenger 1, the first home chess computer. I didn’t like it and asked him to return it. We owned the home version of Pong. One of my dad’s businesses was the Lincoln Racquet Club, home of the first indoor tennis courts in Lincoln, as my dad wanted to play tennis year-round. According to a 1974 newspaper article, $500,000+ had been invested to have eight customers paying $17.60/hour. Despite its initial problems, the Lincoln Racquet Club is still in operation in 2017. When my dad wanted us to partner with Yasser Seirawan on chess flash cards, I told him that I was not interested. From the early years of the Lincoln Racquet Club, I was aware of how tough starting a business could be. Yasser instead partnered with Elmer Hovermale (owner of Elmo’s Books) for Yasser’s Flash Tactics. I have a set of the cards, likely a collector’s item now.

My dad read my monthly Chess Life & Review magazine before I did, which I found annoying because he would ruin the surprise of what my new rating was. In those old days, you found out your new rating on the mailing label of your magazine. You couldn’t just log into uschess.org to find out your new rating. My dad loved buying technology, starting businesses, and playing tennis. He bought me the Fidelity Chess Challenger 1, the first home chess computer. I didn’t like it and asked him to return it. We owned the home version of Pong. One of my dad’s businesses was the Lincoln Racquet Club, home of the first indoor tennis courts in Lincoln, as my dad wanted to play tennis year-round. According to a 1974 newspaper article, $500,000+ had been invested to have eight customers paying $17.60/hour. Despite its initial problems, the Lincoln Racquet Club is still in operation in 2017. When my dad wanted us to partner with Yasser Seirawan on chess flash cards, I told him that I was not interested. From the early years of the Lincoln Racquet Club, I was aware of how tough starting a business could be. Yasser instead partnered with Elmer Hovermale (owner of Elmo’s Books) for Yasser’s Flash Tactics. I have a set of the cards, likely a collector’s item now.

My dad thought I should get around on my own, as when he was 13 he was already driving (illegally) on the country roads near his family’s farm in Elgin, IL. From May of 1979 until June of 1980, I collected 22 Greyhound receipts in my scrapbook. Some of those Greyhound bus trips were from Tacoma to Seattle. Once in Seattle, I would then catch a city bus to the Lake City Community Center, to play in chess tournaments organized and directed by Robert A. Karch. When I first took a Greyhound to Vancouver, BC, at age 13, my dad forgot about the border that I would have to cross. I had no ID, no permission letter from my parents, and less than $50 on me.

The Canadian officials told me that I was likely travelling to be a child prostitute on Granville Street. I cried, showed them my chess clock, and they let me continue on to Vancouver. I stayed with a Canadian who had volunteered to be my chess coach (for free) after my match with Bob Ferguson. Although my first few trips to the Canadian’s apartment were okay (after that first traumatic border crossing, I traveled with a permission letter from my dad), in retrospect “grooming” occurred. The outcome is familiar to anyone who reads salacious newspaper accounts of one-on-one teacher-student or coach-athlete encounters. There were several instances of abuse when I was 14 and 15 years old.

I did not tell my mom until months after the last incident. My dad said that he had trusted the Canadian because the Canadian was married and had a respected profession. When I was 16, my dad drove me to Vancouver so that I could testify at a hearing that my dad had requested in front of the Canadian’s professional board. That board put restrictions on how that Canadian practiced his profession, which pleased me. I did not want any other child to experience what I went through with the Canadian. Because of what my dad and I accomplished through the hearing, perhaps that Canadian never abused again.

Before the first incident of abuse, I was at a normal weight and did not date. After the abuse began, I overate and over-dated. Even after the hearing, my self-image and my behavior did not improve. Despite graduating cum laude at age 17 from the University of Puget Sound, I worked a series of minimum wage jobs (motel maid and front desk clerk in Pendleton, OR; administrative assistant in San Francisco, CA; waitress, cook, and espresso bar operator at the Last Exit in Seattle, WA). I also played a lot of chess. One of my dad’s favorite sayings was “You can never be too rich or too thin.” So, of course, he wanted me to change. He asked me to try two things that had worked for him: the army and law school. Dutifully, I visited an army recruiting office. But I was told that at 5’ 4” and 143 pounds I was too fat to join the army. (The maximum weight in 1983 was 135 for my gender/height/age.) My dad was disappointed, as he had fond memories of serving during the Korean War in the army’s Judge Advocate General’s Corps.

I dropped out after one semester at the University of Washington School of Law. Then I earned my teaching credentials at the University of Washington. At age 21, I taught summer school (a high school credit recovery program) at Kelso High School (WA). I celebrated my 22nd birthday on the same day that one of my summer school students turned 21 years old. After teaching for that summer of 1987 and then for two years (1987-1989) at Bakersfield High School (CA), I began a Ph.D. program in education at UCLA, married, and had two children. I took the maximum amount of leave from my doctoral program as my family established itself in Texas. Drafts of my dissertation went back and forth, via surface mail, between me and my committee chairs.

In 1999, I finished my Ph.D. and became a senior lecturer at The University of Texas at Dallas, working half-time for every fall and spring semester, a position I still hold today. Teaching online facilitated my stay-at-home parenting. Since I teach online, I teach from home. Most teachers have to actually show up in person. When I taught at summer chess camps, I brought my children along as chess campers. My dad divorced my mom, his second wife, and remarried in 1998 in his new home state of Florida. I never met his third wife and her two children. And I rarely saw my dad after his third marriage. However, I wrote about my dad in some of my articles. I wanted him to know that I was thinking about him. After I emailed him my article on Bob Ferguson, he emailed back his legal opinion on the Trump travel ban case. Our last email exchange, and the last time I heard from him, was after I sent him this article, where I had once again mentioned that my dad had taught me chess. My dad replied via email, “I printed the article. It was very nice and complimentary. Chess certainly has played a big part in your life.” I followed a protective-helicopter model compared to my dad’s free-range parenting model. This article highlighted my negative Canadian experiences as a young teenager, reminding other parents to never leave their child one-on-one with a coach or teacher. Know the signs of abuse. And pay attention to where national borders are! On the other hand, I respect my dad for believing me about the abuse and for helping me follow through with bringing that Canadian to justice. It is important to support victims of abuse and my dad supported me. He loved me and I love him.

I had positive experiences growing up with chess too. Some of the people I met through chess decades ago are still my friends today. As a teenager, I was one of the most active female chess players in the U.S. If I had not played all of those games, I might not have become good enough at chess to win the 1989 U.S. Women’s and to earn a peak US Chess rating of 2260. Without my dad, I likely would never have learned the rules of chess, much less become a master of it.

WIM Dr. Alexey Root is a frequent contributor at US Chess and an author.

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (13)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)