Editor's note: This story first appeared in the March 2025 issue of Chess Life magazine, and is re-published here along with this collection of William A. Scott, III's games (including 47 additional games).

Consider becoming a US Chess member for more content like this — access to digital editions of both Chess Life and Chess Life Kids is a member benefit, and you can receive print editions of both magazines for a small add-on fee.

Download a PDF of the print version of this story here.

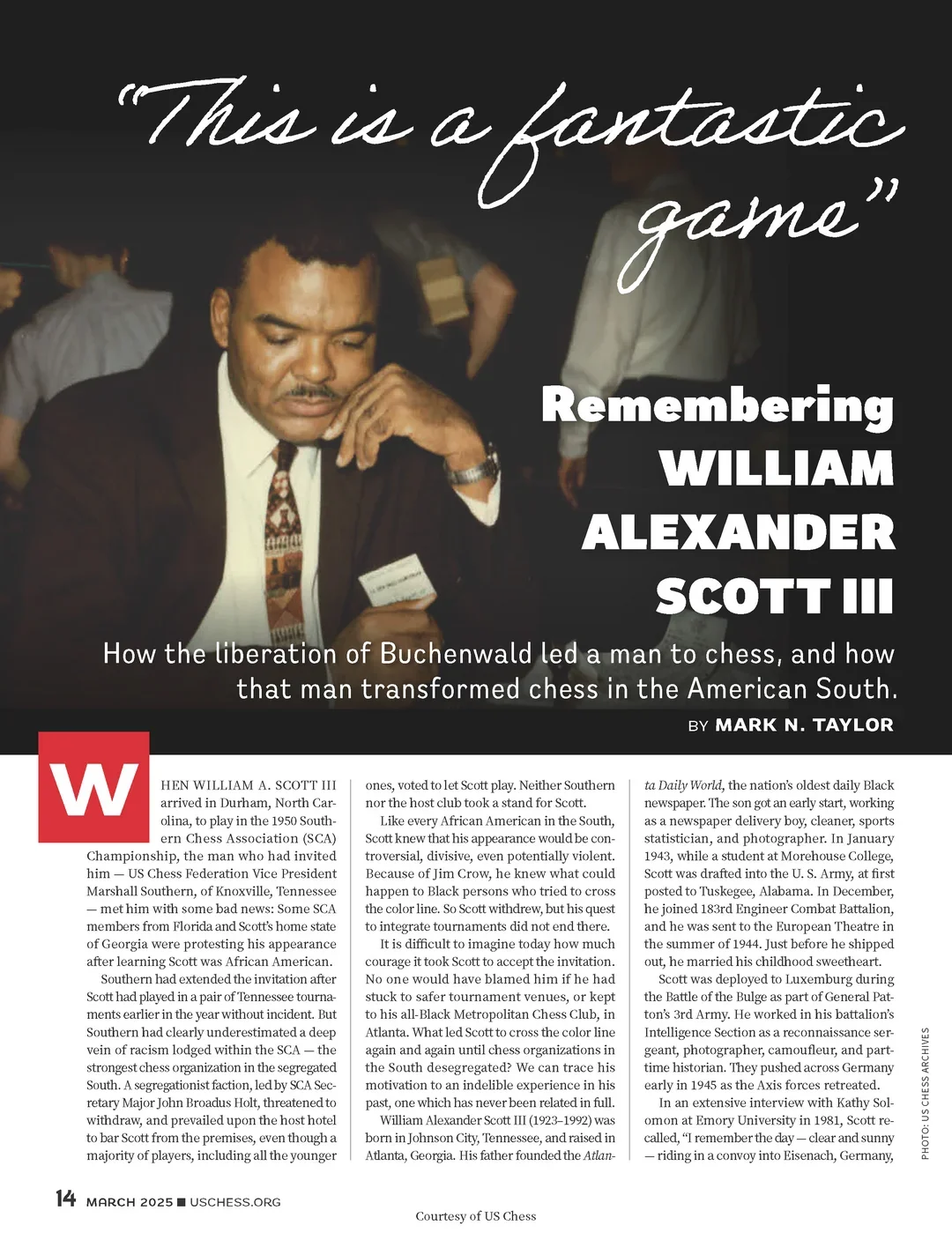

When William A. Scott III arrived in Durham, North Carolina, to play in the 1950 Southern Chess Association (SCA) Championship, the man who had invited him — US Chess Federation Vice President Marshall Southern, of Knoxville, Tennessee — met him with some bad news: Some SCA members from Florida and Scott’s home state of Georgia were protesting his appearance after learning Scott was African American.

Southern had extended the invitation after Scott had played in a pair of Tennessee tournaments earlier in the year without incident. But Southern had clearly underestimated a deep vein of racism lodged within the SCA — the strongest chess organization in the segregated South. A segregationist faction, led by SCA Secretary Major John Broadus Holt, threatened to withdraw, and prevailed upon the host hotel to bar Scott from the premises, even though a majority of players, including all the younger ones, voted to let Scott play. Neither Southern nor the host club took a stand for Scott.

Like every African American in the South, Scott knew that his appearance would be controversial, divisive, even potentially violent. Because of Jim Crow, he knew what could happen to Black persons who tried to cross the color line. So Scott withdrew, but his quest to integrate tournaments did not end there.

It is difficult to imagine today how much courage it took Scott to accept the invitation. No one would have blamed him if he had stuck to safer tournament venues, or kept to his all-Black Metropolitan Chess Club, in Atlanta. What led Scott to cross the color line again and again until chess organizations in the South desegregated? We can trace his motivation to an indelible experience in his past, one which has never been related in full.

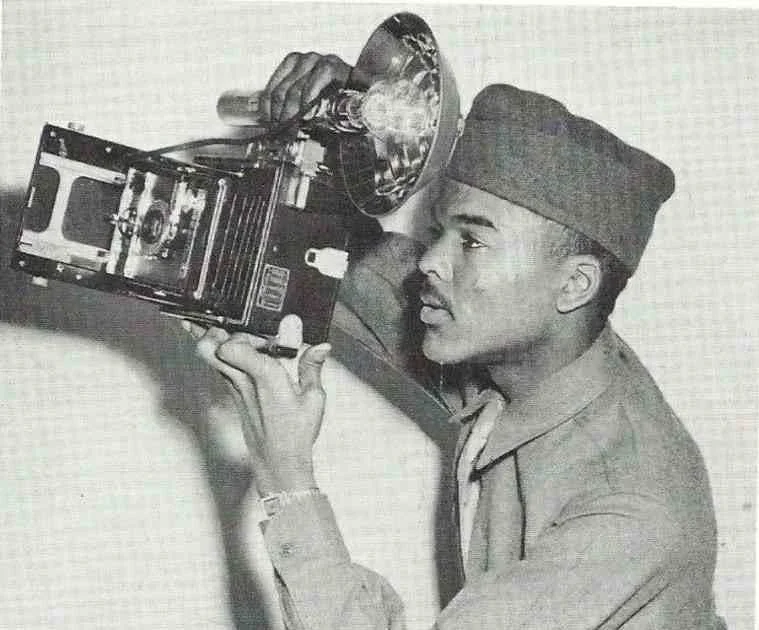

William Alexander Scott III (1923–1992) was born in Johnson City, Tennessee, and raised in Atlanta, Georgia. His father founded the Atlanta Daily World, the nation’s oldest daily Black newspaper. The son got an early start, working as a newspaper delivery boy, cleaner, sports statistician, and photographer. In January 1943, while a student at Morehouse College, Scott was drafted into the U. S. Army, at first posted to Tuskegee, Alabama.

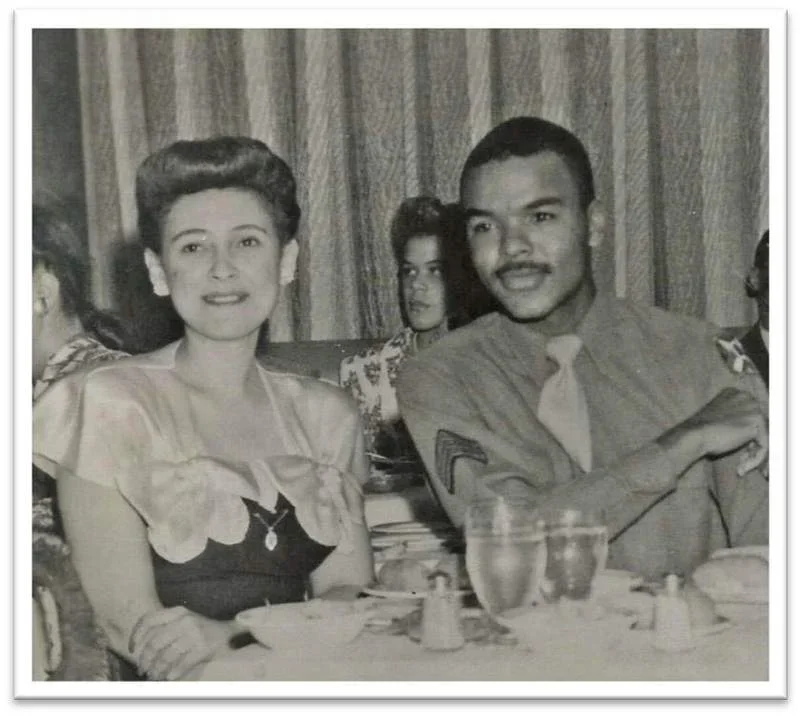

In December, he joined 183rd Engineer Combat Battalion, and he was sent to the European Theatre in the summer of 1944. Just before he shipped out, he married his childhood sweetheart.

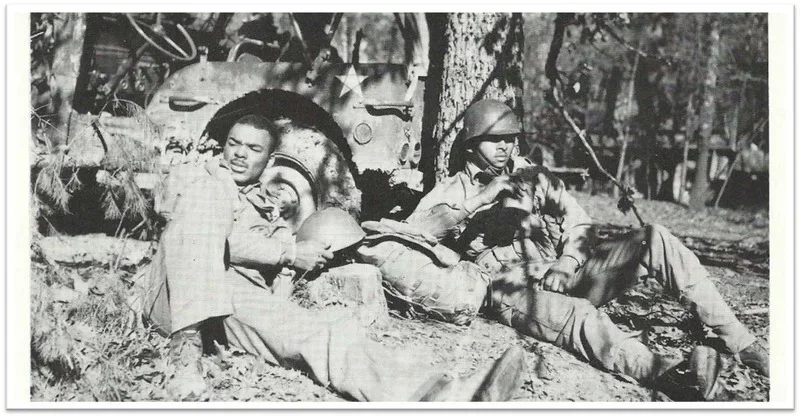

Scott was deployed to Luxemburg during the Battle of the Bulge as part of General Patton’s 3rd Army. He worked in his battalion’s Intelligence Section as a reconnaissance sergeant, photographer, camoufleur, and part-time historian. They pushed across Germany early in 1945 as the Axis forces retreated.

In an extensive interview with Kathy Solomon at Emory University in 1981, Scott recalled, “I remember the day — clear and sunny — riding in a convoy into Eisenach, Germany, on April 11, 1945, as World War II was ending, and a 3rd Army courier delivering a message to us to continue on to a concentration camp.” That was Buchenwald, and what the 22-year-old Scott saw that day changed him.

Although the battalion had been warned about conditions, Scott said, “We drove in, and I said, ‘Gosh, it’s not as bad as they say. It looks just like a regular prison.’” As they drove around, he soon realized he was wrong. “As a matter of fact, I ended up saying it was worse [than it had been described.] … And I said, ‘There’s no way you could describe it’.” He began taking photographs as he confronted horror after horror that the silent survivors kept pointing out to him. Eventually, “I put my camera up after a while and I just stopped taking pictures.”

In one of the barracks, he said, “Some of the survivors, with their clothing torn and their body exposed, were kneeling on the ground playing chess out of some makeshift sets, and they were just oblivious, almost, to what was going on around them even. And I said, ‘Well, this is a fantastic game. ... This can keep your mind from going off the deep end, so to speak’.”

Later in the day, Scott and the 183rd moved out. In July, he was shipped to the Pacific Theatre, a deployment that started with 65 days at sea.

Scott’s mind kept going back to the Jewish prisoners he saw, so absorbed in their game they were hardly aware of the horror of the concentration camp. Scott had just learned to play a few months earlier in Luxemburg, and while at sea, “that’s when I really got involved” in the game, to counter tedium and troubled thoughts. Eventually, “I had begun to develop some feeling for it.”

After a few months in Okinawa, Scott took a ship back to the States. He recounted a conversation he had on board with a fellow Georgian, a white man who told him: “‘Look, Scott ... when we get back to Georgia, do you think you’re going to have your rights? You’re not going to have any rights unless you stand up and act like a man.’” Scott remembered thinking, “Maybe he would kick me around if I let him. And this is what he was trying to tell me — that this has been part of the problem, that people have allowed themselves to be kicked around.”

When Scott took the risk of playing in the 1950 SCA Championship, he chose not to be kicked around. When he saw the controversy his presence created, he voluntarily withdrew. This was a gracious action, but also strategic. The majority of the players were already on his side, and in fact said they would not have the next tournament in any city that would not accept Black participants. He realized that he had a winning position; there was no need to force it. He chose the path of patient nonviolence that would become the hallmark of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Civil Rights activity.

And his stance worked. News of Scott’s treatment traveled nationwide and chess clubs as far away as Los Angeles sent petitions in protest to US Chess. By the summer of 1951, the Southern Chess Association had split into two factions over the integration question. An integrated SCA championship tournament was held in Asheville, North Carolina; Scott finished 11th out of 22, scoring 4½/6, and tied for first in the rapid transit division with 6/8. While a minority of members held a segregated tournament in Tampa, Florida, members at the Asheville tournament passed a resolution approving Scott’s participation and decrying racism in chess. Because the integrationists were the larger group, younger, and included the best players, the segregationist faction soon died out.

Scott continued to play in the South, scoring a string of positive results that stands as testament to his strength of spirit. He improved his play over the decade through correspondence chess as well as various regional tournaments, including the 1958 Florida Open, which he won. And all through it, he wrote chess articles and press releases for the Atlanta Daily World, making it possible to get some sense of how much chess activity was going on in Black Atlanta during the era of segregation — history that has been neglected by other periodicals.

At the same time, Scott, still a class player, also played in national tournaments. He attended the first of his many U.S. Opens, in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1951. The only Black person among 98 players, he finished with 6½/12. He also played in the National Amateur Open in 1961, finishing 25 out of 140, and again in 1962, finishing sixth on tiebreaks out of 143.

In his own state, however, organizers of the Georgia Open declared it would continue to be “limited to white Georgia citizens only,” even though integrated tournaments were beginning to be held in other southern cities.

It wasn’t until March 1961 that Scott played in his first tournament in Georgia — the Atlanta Open, sponsored by the Atlanta Chess Club. The Atlanta Daily World reported that the club “in a meeting just before the start of the tournament last Friday voted better than 2 to 1 [to] open the competition to everyone regardless of race.” Scott scored 4½/6.

In 1963, the fully integrated Atlanta Chess Association elected Scott vice president. He went on to serve two terms as president, 1965–1967.

Scott was indisputably one of the strongest players in the state, but racism in Georgia chess still dogged him. Scott and other Black chess players were barred from participating in the 1962 Georgia Closed Championship. “The failure of the Georgia Chess Association to accept us as participants is not understandable,” Scott wrote in the Atlanta Daily World, “in light of the opening of tournaments to all for such sports as tennis, roller skating, baseball and bowling in the Greater Atlanta area.” Scott contrasted this treatment with a Tennessee Chess Association invitational in Nashville, which he turned down so that he might play in the Georgia championship.

The following year, Georgia members voted to make the championship rated, which required them to follow the US Chess Federation’s non-discrimination policy. Perhaps as a commentary on his treatment, however, there is no record of Scott playing in a Georgia Closed Championship.

In 1963, Scott was the top Georgia finisher in the Georgia Open, in Columbus. The April 1963 Georgia Chess Association newsletter, however, failed to mention his name in their tournament report, only mentioning the overall tournament winner, Milan Momic, of Alabama.

In 1967, Scott was both the Atlanta Chess Club Champion and Speed Champion. In that year he also chaired the host committee for the 68th Annual U. S. Open Chess Championship tournament in Atlanta (where he placed 26th out of 168).

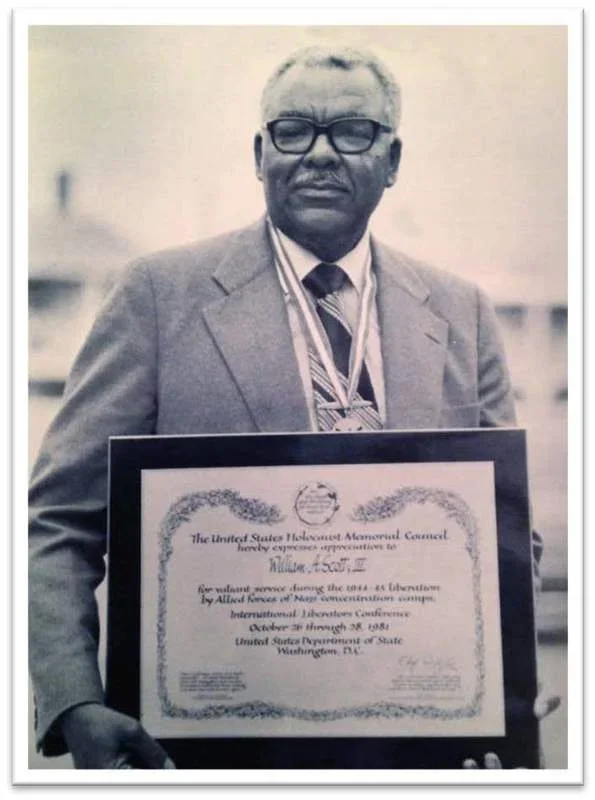

Scott passed away in 1992 after flourishing in many roles: businessman, film critic, radio show host, photographer, coach, and historian for the Atlanta Chapter of the Tuskegee Airmen. In 1987, Mayor Andrew Young asked Scott to serve on the planning committee for the city’s 150th anniversary. Governor Joe Frank Harris appointed Scott a charter member of the Georgia Commission on the Holocaust in 1981, and President George H. W. Bush appointed him to the United States Holocaust Memorial Council in 1991.

Chess and Civil Rights are only two facets of who W. A. Scott III was. And yet, chess is at the heart of what formed him and who he became.

In addition to Kathy Solomon’s interview with William A. Scott III (26 Nov 1981. Emory University, Atlanta, GA), information for this article was primarily drawn from periodicals: Atlanta Daily World, Chicago Defender, and Georgia Chess Letter.

Editor’s note: the following five games were annotated by Rick Massimo for the print version of this story. An archive with 47 additional games can be found here.

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (8)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)