Editor's note: this story first appeared in the November 2024 issue of Chess Life magazine. Consider becoming a US Chess member for more content like this — access to digital editions of both Chess Life and Chess Life Kids is a member benefit, and you can receive print editions of both magazines for a small add-on fee.

We also provide a pdf version of the article for those interested in reading it in full layout.

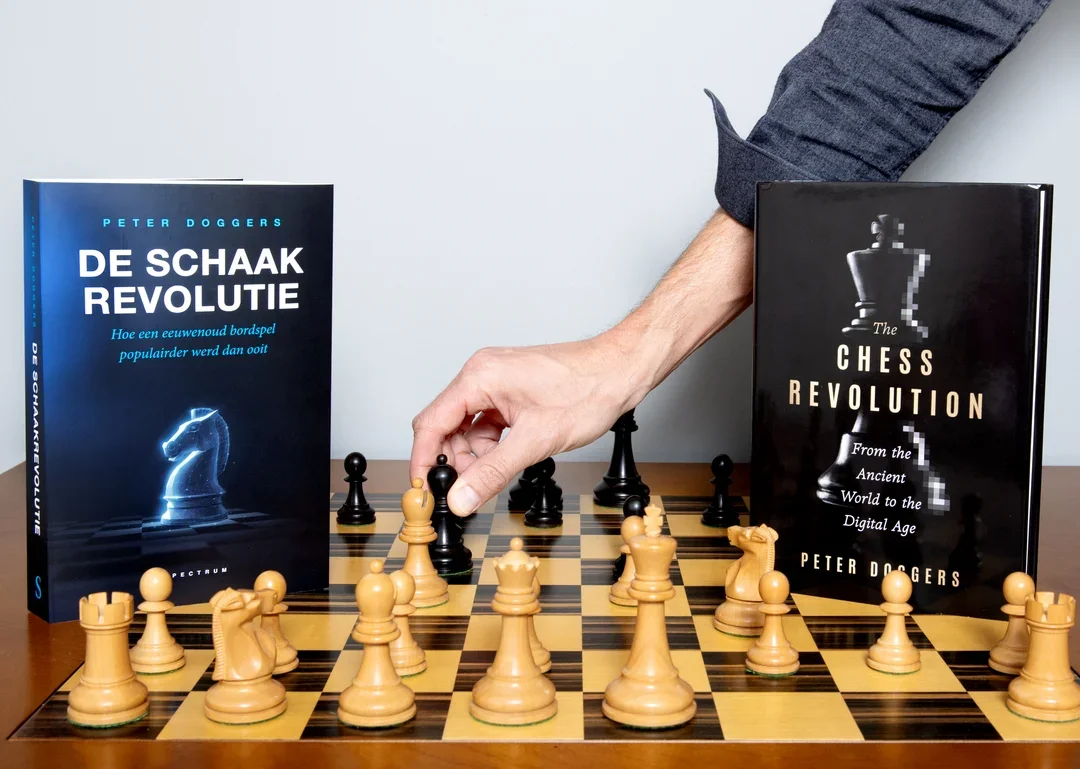

Peter Doggers is one of the elder statesmen of online chess journalism. In 2007 he launched ChessVibes, one of the best chess news and video sites of its day, and followed that with the ChessVibes Openings and ChessVibes Training subscription newsletters. He moved to Chess.com in 2013 when they acquired ChessVibes, and today he serves as their director of news and events.

The Chess Revolution is Peter’s first book, and when I heard he was writing it, I couldn’t have been more pleased ... or more jealous. This is a book I would love to have written, but having read it, I’m acutely aware that Peter did a much better job than I could have dreamed of doing.

When I spoke to Peter in late September over Zoom, he was at home in the Netherlands and had just received his copies of the English edition. Our discussion was free-ranging, and while it gives you a good sense of the book’s themes, I think we also ended up in some interesting places. The interview has been edited for clarity and space, and any editorial clarifications appear in brackets.

I can’t recommend The Chess Revolution highly enough to Chess Life readers. It arrives on American bookshelves Oct. 29, and you should be able to find it in all of the usual places. Perhaps your local, independent bookseller might be able to get you a copy?

John Hartmann (JH): The Chess Revolution is a very nice introduction to the history of chess, as well as a cultural/technological history of the game. It works for long-time fans, I think, but also for readers who are just interested in learning more about chess.

Peter Doggers (PD): Yeah, that’s what I was trying to do. It’s a bit of a challenge, because how do you write a book that is interesting for chess players and non-chess players? I hope a bigger audience will be interested in it as well, because it would mean that the book itself would actually be some kind of extra promotion for the game. So I really hope it will catch on outside the chess world too.

JH: You tackle some big issues in the first section of the book, which you title “Chess as a Cultural Phenomenon.” You talk about the history of chess in popular culture, about chess in the arts and chess as a kind of art.

You take on the relationship between chess and science, about the famous idea of chess as Drosophila for psychology and for computer science. And you end by talking about genius, and the three biggest geniuses of our game: Fischer, Kasparov and Carlsen. Along the way, you had a lot to say about the question of gender equality in chess, and why there seems to be a gendered gap in ratings.

Let’s start there: Why do you ultimately think this gender gap exists? You talk about a lot of different ideas, you cite a lot of experts, but how do you understand the reasons for this gap?

PD: Well, first of all, let me say that this part of the book comes from the fact that I’ve been writing about chess for almost two decades, and it’s a topic that sort of comes back every couple of years. The big moment for me was Nigel Short’s controversial column in 2015 in New in Chess when he was saying, well, the brains might actually be different, and why shouldn’t we simply accept that instead of continuously saying that it’s not true? Every few years something pops up again.

Very often there will also be articles in the mainstream media, and many of those articles will cherry-pick a little bit towards certain research — something, by the way, I also noticed happening in the debates over whether chess is just beneficial for children, for people as they age, etc. There’s so much fragmentation in reporting on this.

So I gave myself the task of researching the research. And what I discovered is that it’s a super complicated topic. That’s the most important thing about gender, and about the two issues that are actually at stake, the first of which is the participation gap. If you look at the full FIDE rating list, it’s like 11% female worldwide. Interestingly, in the Netherlands and Denmark — both very affluent European countries — it’s even less, maybe 5% participation.

An aside: I don’t think any federations are allowing for more gender possibilities beyond male and female in their reporting. And I think we should consider that in the near future.

Along with the participation gap there is the performance gap. Females are not reaching the highest rating levels. At the moment there is no female player in the top hundred. Only three — Maia Chiburdanidze, Hou Yifan, and Judit Polgar — have ever done so. And Judit is the only player who entered the top 50. She ended up reaching number eight in the world.

I think that the participation gap actually explains the achievement gap to a large degree. But there are so many more things. My answer is that it’s a very complex system of factors that are influencing this situation. They all work together; they influence each other, and it’s a very difficult topic to have clear opinions about. You have to make sure that you are looking at everything that’s at stake.

Why are fewer girls getting into chess? Why do they drop out at a higher rate? What are the reasons for, and benefits of, separate classes and tournaments for girls? Then there’s the whole issue with gendered titles, with the effects of lesser prize money, and the very real psychological effects we know exist when women play against men. They score differently if they know they are playing against other women, or if they don’t know the gender of their opponents.

There’s so much that has an effect on the situation. I think just about everyone agrees that we would like to have more women playing, and we would also love to have them perform better, but how to go about that? There are like 15 different factors and you have to take them all into account. I think we have to continue researching which factors are most important, how they relate to others, and go from there.

JH: That is probably the most complete answer I’ve heard on this topic ever.

PD: And at the same time, it’s not saying that much!

JH: In this first section you talk about art and science. For you, after having written this book, what’s your take on the famous question: Is chess an art? Is it a sport? A science? Is it perhaps a religion, as the Hungarian minister said at the Olympiad opening recently?

PD: I like that. Yeah, actually that also makes a little bit of sense.

Well, I’m afraid I’m going to be boring. The answer is basically that it’s all at the same time, depending on the context, of course. And that’s maybe also what’s so beautiful about it, that there’s not many activities in life that you can basically categorize in all those different areas of society. Which is also what I’m sort of demonstrating in the book: It is just incredible that you come across chess in all those different areas.

I don’t think there’s anything else you can really point at with similar reach. There’s no other game or leisure activity that you will find in an art museum, but also in a Netflix drama. When you walk around in the city, there will be a table in the park. Chess is everywhere! It’s in language, in the expressions that we have continuously use, especially in politics ... it’s so rich that even after writing this book, it’s a bit of a mystery, to be honest.

This game is really a bit magical. I’ve tried to unravel it through journalism and research. I give a lot of people a voice in the book too. It’s a collection of a lot of smart things that have been said on these topics by a lot of good writers, and I add some of my own thoughts.

JH: While the first part of the book may be a bit familiar to some readers if they’ve been around chess for awhile, I think the second and third parts are going to open a lot of eyes, especially for those who maybe are newer to the game. Your book title is apt: I don’t think you can understand modern chess without grappling with the revolutionary impact of the computer, the internet, and streaming.

Let’s talk a little bit about the history of computer chess. I think you do a masterful job with the history. You write about Claude Shannon, Belle, and David Levy’s 1968 bet that no computer could beat him in the following 10 years. And I love a particular line you quote — that despite eventually losing to the machine, the 10-year bet turned into a 21-year bet that gained him lots of good publicity.

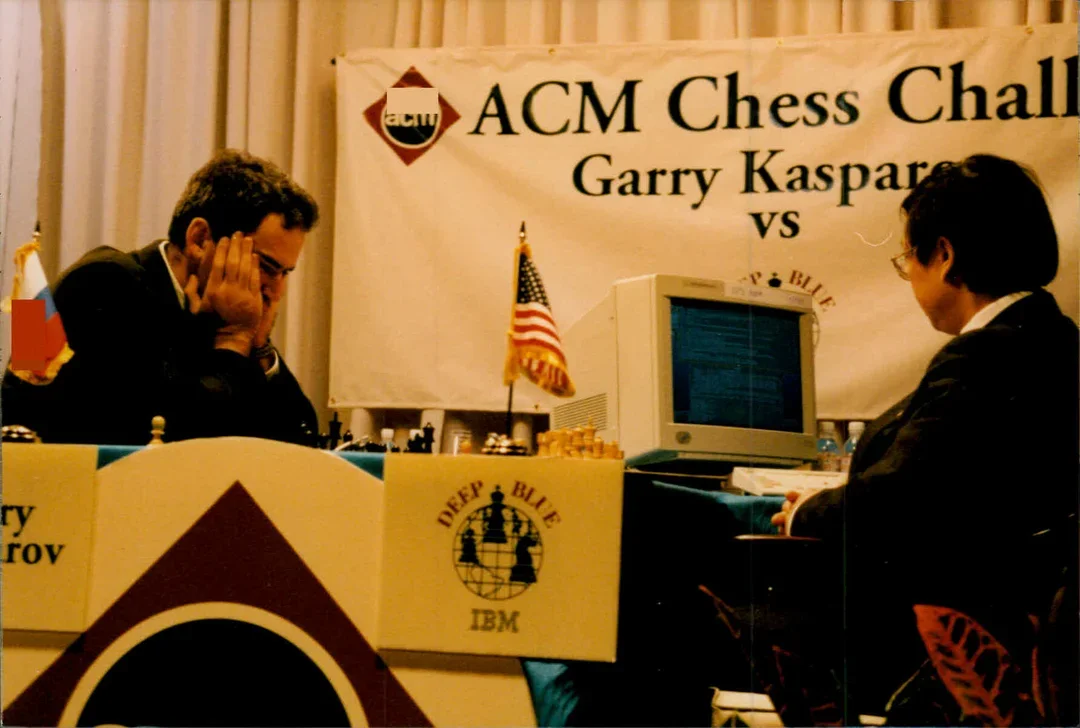

You make the claim that we shouldn’t view Kasparov and Deep Blue as the really revolutionary moment in the history of computer chess.

PD: That was the moment that the strongest human player in the world lost a match for the first time. But it’s quite obvious that Kasparov was not playing at his best level. He suffered psychological problems while playing the machine, but especially from playing a machine that had a team around it, including grandmasters who helped create Deep Blue’s opening repertoire.

What I found very interesting is that, later in his career, Kasparov started to admit that what had gotten into his head were these moves that looked very human. He wanted to see the computer logs, and the logs were not released. And he had this feeling that there was some human interference.

After the match he compared these moves to Maradona’s “Hand of God,” which is a beautiful football-themed predecessor of Magnus’s cheating accusation. Carlsen charged Niemann with using computer assistance, while 30 years ago, it was human interference that was the problem. It’s a very funny mirror.

If you look at Danny King’s interview with Kasparov after Game 3 of the 1997 match, Garry already says that if someone has psychological issues while facing the machine, they might lose. Looking back, it’s clear that he was constantly thinking about the second game [where Deep Blue played a poor 45th move that allowed Kasparov a chance to draw, which he missed], that it got into his head, and the loss of concentration affected his play. He was admitting that he couldn’t focus on just playing good chess.

If he would’ve just played to his abilities, Garry would probably have beaten Deep Blue in the second match. Maybe he would’ve lost a third match. But he was probably equal to the machine, and I think he was still slightly stronger. I think most experts agree on that.

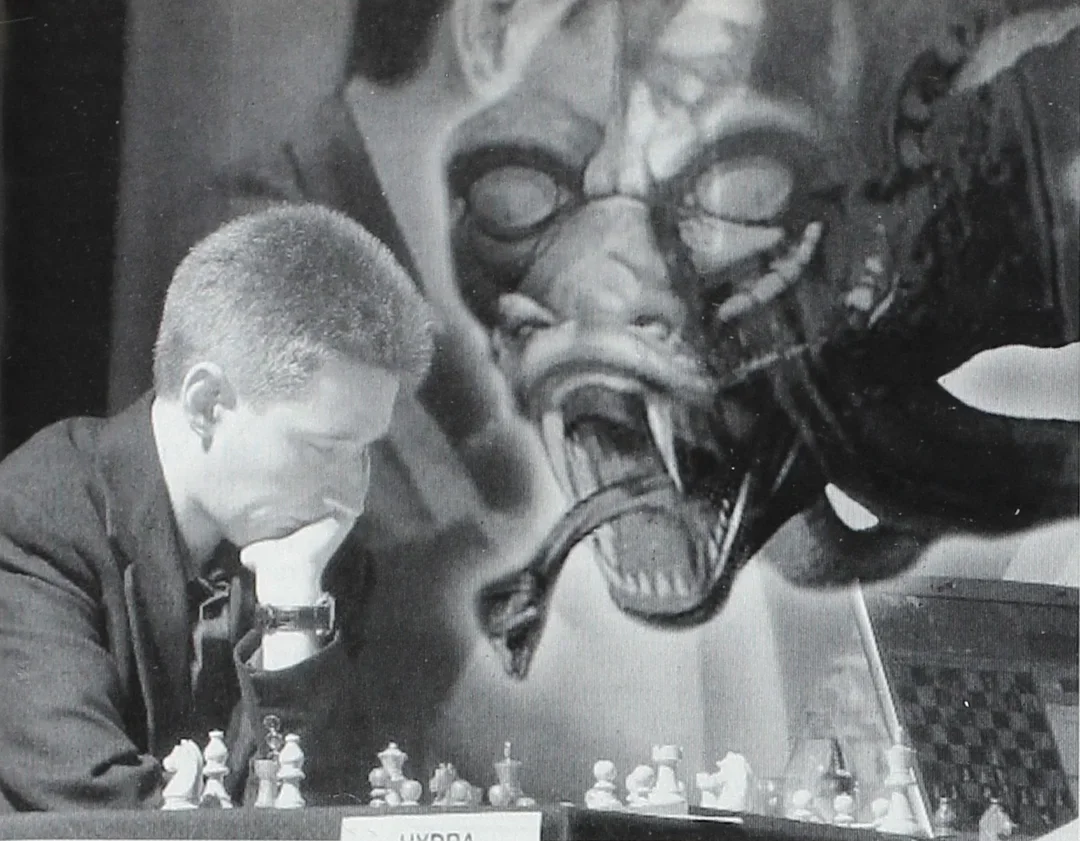

People outside the chess world don’t know that man versus machine matches continued. The hardware was weaker — IBM did not let Deep Blue play again after defeating Kasparov — but the software got stronger and stronger. Kasparov played two more matches against Deep Junior and Deep Fritz, I believe, and Kramnik also played a couple of matches against Fritz, one of which included the game where he famously allowed mate in one. Around this time — the early 2000s — humans were still doing sort of OK. And then they got into trouble.

I think the real turning point was when Mickey Adams lost to Hydra, a supercomputer from Abu Dhabi, in 2005. Maybe if he’d lost 3½-2½, it wouldn’t have been such a key moment. But he lost 5½-½, and I still remember that we were like, wow. Mickey Adams had a pretty good playing style for playing against computers in those days, and he was just completely crushed.

After that, there were not that many matches with computers. At least for the chess insiders, there was a clear recognition that, OK, we lost the battle. We have to stop this.

JH: At that point things shifted from competition with engines towards how to use this new tool. You do an excellent job of talking about how certain players — most notably Kasparov — began to use chess computers and chess engines in their preparation.

PD: Although that was of course already in the mid-’90s, yeah, even before Deep Blue. For example, Garry beautifully won Game 10 of the 1995 world championship match against Vishy Anand in an Open Ruy Lopez by sacrificing a full rook on a1, and after the game he was like, “Yeah, this was all computer.” He’d worked it out with Fritz. And it’s like, wow: a world championship game decided by a computer. That was historic.

But five years later ... I talked about this with Anish Giri, and he said that it might have been the engine’s misevaluation of the Berlin [that White had an advantage in the main line] that strengthened Garry’s stubbornness in trying to break it down over and over again. He played this Berlin endgame four or five times against Kramnik, and he didn’t manage to win a single game against it.

JH: I thought you did a particularly good job of describing how engines have changed today. And we’ll talk in a minute about AlphaZero and Leela and the new Stockfishes. But I wanted to ask about this interview you did with Ivan Sokolov.

Sokolov is such a fascinating character in the world of chess today. He’s someone who was classically trained, but also who now works with all of these young talents, and he had a lot to say about preparation and the role of engines in it.

PD: This was based on an interview that I did with him for Chess.com after Uzbekistan won the 2022 Olympiad in India. I don’t have the correct quote fully in my head, but I know that he talks about showing opening positions to players like Firouzja or Abdusattorov, and they come with the strangest moves. And he would initially criticize their moves and then the young player would say, “Yeah, but the computer gives an advantage.”

They would then look at it together with the group, and sometimes he would sort of agree with the computer evaluation and they would begin to understand it. And then they’d decide, “OK, it’s a good move; let’s play it.”

But sometimes they would come to the conclusion that while it actually might be a good move for a computer, it doesn’t work for a human being because it’s simply too hard to understand. They’d decide that it doesn’t make sense to play the move over the board even though it has a good evaluation because after that, you might not understand how to proceed. It’s just too deep and weird and strange. It’s too far away from how we humans know how to play chess, so it’s better not to play it in that case.

What I do think is that a lot of strong young players are not being brought up the same way anymore. The advice used to be “Make sure you see the games of the World Champions; make sure you see some of the best endgames of Capablanca, some of Alekhine’s wild games.” I remember, maybe 15 years ago, wasn’t there an interview with Nakamura where he claimed that he had never seen a Smyslov game or something like that?

JH: I remember that.

PD: Yeah. And we all thought, “How is this possible?” Hikaru was maybe the first example of someone who ignored the really classical upbringing and instead, he just played hundreds of thousands of online games. Now we know that that could simply be an alternative way of getting to be very strong, but it’s radically different.

JH: Do you think anything is lost in this for average, everyday players? The idea that you don’t need to know the classics anymore?

PD: I don’t get the feeling that the younger generation is enjoying chess less than we were. They are fascinated by the game, but they also would simply like to win their games. Hard to say.

Magnus actually read a lot of books, and he had a fantastic memory. So he still had that very classical upbringing, but he also played a lot online. I think Magnus is sort of a great combination of the two worlds these days. And I think that does help him to remain on top, besides having a very large reserve of talent of course, and natural intuition and all that.

But I would not be surprised if, even for those young players who have reached a high level with a lot of modern training materials, I would not be surprised if someone like Sokolov at some point says, “Okay, it’s all very nice, but now you’re going to look at this Capablanca endgame anyway, because I just want you to know it. Even though you might already understand it, but are you telling me you’ve never seen this one? That’s ridiculous. Go study it right now.”

JH: Then we get to AlphaZero.

If there is a revolution in chess ... I mean, Petrosian said the young players were all children of the Informants, and then it was, they’re all children of ChessBase, and now they’re all children of AlphaZero. Talk a little bit about why AlphaZero was so important to so many people.

PD: Well, for starters, it was just like Deep Blue. Suddenly out of nowhere it was clearly the strongest computer in the world, and especially the crushing way it defeated Stockfish 8 at the time ... that was also a feeling like a revolution: “What the hell hit us?”

I was at the London Chess Classic when it came out in December 2017. Magnus’s second, Peter Heine Nielsen ... he said, “I always wondered what alien chess from another planet would look like. And I think that today we see it.” And Kasparov said something along the lines of, “Yeah, I’m also very happy that it plays kind of in my style.”

That’s the other thing of course — besides being incredibly strong, the other issue was the playing style, the long-term piece sacrifices and aggressive play, and the famous running of the rook pawns up the board. There were a lot of things that were very attractive to look at, to be honest. The games that were published were quite nice.

Matthew Sadler and Natasha Regan wrote this very good book about AlphaZero called Game Changer, which was a great title by the way, because it really was a game changer for chess. And then I remember this article in New in Chess where Peter Heine Nielsen gives a bunch of examples where Magnus had been clearly been influenced. He really tried to play a little bit like AlphaZero in the tournaments that followed, in 2018. So that was also beautiful to see.

Those things combined were revolutionary, definitely. But an even bigger effect came when Leela, an engine modeled after AlphaZero, became available, and then later on the NNUE versions of Stockfish were developed and people could actually play with them and analyze with them. These new AI-influenced engines started to influence opening preparation immensely, and we still see it happening now. The level of grandmaster preparation is just amazing. It’s incredibly high.

JH: You spoke to Peter Heine Nielsen quite a bit for the book, and I liked what he said about how the engines are too good now. Any advantage he used to have in terms of opening preparation is now cancelled out by the fact that everyone has these tools.

PD: Yeah, definitely. There’s this example from a few days ago: David Smerdon on board four for Australia at the Olympiad. He played a 10-move draw after a move repetition, and he wrote a long post on Facebook that discussed it. Australia ended up losing the match to Andorra, and he felt really bad about finishing his game after 15 minutes. He wasn’t sure if he should have continued, but he got caught in this theoretical line, and if he would avoid the move — his opponent was like 150 points lower rated, by the way — if he would avoid the repetition, he would get into very murky, complicated theory, and he was convinced that his opponent would know it better than he would. In the end, he agreed to this quick draw, and then his team lost.

And I left a comment that this is the modern world. We live in a world where amateurs can have grandmaster-level opening preparation. I think the level of middlegame play is not that much better, and maybe endgame play might actually be a bit worse than for amateurs 30 years ago. But their opening play is just insane.

And it’s affecting me personally as well. I have a league game tomorrow and I am preparing a little bit, but there’s so much to prepare. With all these Chessable courses, the number of moves that you can actually theoretically try to memorize, even for amateurs — it’s unbelievable, the amount of work you can do. So there’s always this — well, you probably know it. You try to find a balance between staying sane, and just prepping and going along with the rat race, right?

JH: This was me Wednesday night before my local club game, and then of course the guy played 1. d4 and it all went out the window.

PD: Exactly.

JH: The joys of modern chess.

Before we talk about the internet, we should talk about what you call the dark side of computers, which is cheating. You have a chapter on cheating in chess, and of course the example that everyone thinks about is Carlsen’s allegations about Hans Niemann. But you also recount a long history of cheating and chicanery beginning with the Mechanical Turk.

I wanted to ask about the way forward here for us, because technology is always getting better and better and better. You wrote about some people who showed that you could sneak just about anything into a tournament hall without much effort.

Is this something that a normal, everyday player needs to worry about? What effect is this going to have long-term on over-the-board chess?

PD: Well, it’s still a big topic, also thanks to the efforts of Mr. Kramnik, for example. We keep on talking about it. It keeps being an issue.

We have to have anti-cheating measures in tournaments. The main issue for over-the-board play is that there are so many small open chess tournaments with very small budgets where organizers are working with a tiny team. They’re not able to have a proper metal detector, for example, or random checks or whatever. There’s just not enough manpower and not enough money to properly deal with it.

I think there should be a role for FIDE to help organizers with this part of organizing a tournament. I think they have a responsibility towards organizers to help them understand how to organize a proper tournament and how to implement proper fair-play measures.

Once this is happening, I think players will simply get used to it. I like what they’re doing in Wijk aan Zee for the amateurs: They do random checks. Basically they announce, “During the round, we’re going to choose three or four players and we’re going to check you with a metal detector.” It’s not ideal, but for the majority of people, it’s not a bother at all.

It’s going to be very difficult to rule cheating out completely because of the technology. The devices are getting smaller and smaller. The little earphones are the size of a piece of rice, and you can hide it deep in your ear. That said, we should not overestimate the dangers either. We all agree it’s a bad thing; we work against it, and that’s enough.

The online situation is of course a completely different story. I do think that, on lower levels, there’s probably still a lot of cheating happening. The only thing we can really do is trust the algorithms, the software that the platforms have developed. I’m connected to Chess.com myself. I believe that we have most likely the strongest algorithm to fight against cheating. And when we are confident that someone has broken our terms, we only do that when we are like 99.99999% certain the statistics make it pretty impossible for someone to have played on that level by themselves.

Kramnik wants us to start banning players if we are 90% certain that they are cheating. And we simply cannot do that, because then we’re going to ban too many players that are actually outliers, that just had a very good run.

The result is there will be some cheaters that are still playing on our site because we don’t have enough data yet to be certain. We kind of know that someone’s doing it, but we cannot ban them yet. It’s an issue that cannot be 100% solved, I believe.

JH: Well, this is a nice place for us to transition to talking about the third part of your book, which is about the internet. And you begin with a history of playing sites and the Internet Chess Club (ICC).

You talk about the rise of ICC and how it became so important, how it was such a place of its time with the chat channels, which were kind like IRC chat or Instant Messenger chat.

And then you describe how Chess.com came along and, as browser technology became better, it began to take over as ICC stagnated. And you recount about the strange origin story of Lichess. The driving force behind Lichess, Thibault Duplessis, was once an employee for Exercise.com, which was a sister site to Chess.com.

PD: It’s a funny little detail that Thibault actually worked for Erik [Allebest] and Danny [Rensch], or with them at least.

JH: It occurred to me as I read your book that there’s really a common thread here, and that’s Hikaru Nakamura. If you think about the trajectory of internet chess, beginning with ICC, that’s where Nakamura became a legend. His blitz matches, his bullet matches, the non-stop kibitzing while he was playing. Then he moved over to Chess.com and got a non-exclusive contract to play there. Soon he was the biggest chess streamer, and one of the biggest streamers in the world.

PD: Yeah, it’s true. Actually, it’s interesting ... I did not put that much emphasis on Hikaru’s legendary status on ICC. Perhaps I should have emphasized that a little bit more because I do remember it quite well.

Hikaru played an important role in the transition from ICC being the dominating platform to Chess.com being the dominating platform. And then, of course, he had a big role in the development of chess streaming during the pandemic and continuing after. So in that sense, you’re right — Hikaru is an important figure in all these developments.

JH: I was glad to see mention of Charlie Drafts. Tell us about him.

PD: Well, the story is basically that his life was saved because of the community on ICC.

I think he was an amputee who typed with a stick in his mouth, and he started typing in a chat channel that he wasn’t feeling very well. At first, some people thought he was joking, and then he was like, “No, no, I’m having physical problems and I think I need help.” I think one of the admins asked for his address and decided to call 911. An ambulance drove to Charlie’s house, they broke down the door, and they managed to stabilize him in the hospital. He was saved by the quick reaction of the community.

JH: I like that story because it evokes a time and a place before the internet was so heavily commercialized. ICC was for-profit in 1996 when this happened, but there was still this idiosyncratic, chatty community.

PD: They had all these great sub-channels for chat, and you could actually create your own channel. I remember I was in a friend’s channel with like six other people, and every time we were online, we’d all talk. It feels very similar to what we have on Whatsapp these days, where you are in all these groups of different sizes, but they’re all based on something you have in common. It’s not something Chess.com or Lichess have, and maybe we should.

What also made it so nice was that it was new, and it wasn’t so massive yet. We weren’t on a platform with millions of other people, so a channel like that wouldn’t be flooded with loads of people who are going to spoil things. That’s one issue with platform growth — there’s always going to be a percentage of people who just want to destroy a forum or comment section.

I had this same problem with my own website, ChessVibes, that I ran before I joined Chess.com. In the early days, there was also a relatively small community with all these very nice discussions below articles, really high-level stuff. We saw something similar on Mig Greengard’s Chess Ninja site. The discussions below that were also very interesting.

Anyway, at some point, your audience becomes too big, and the comments section suffer. People leave weird comments. For example, my absolute favorite [sarcasm] are the people who want to be quick. After 30 seconds you see a comment and that says, “First.” As soon as that happens to a platform, just by sheer volume, a lot of those people who used to leave interesting comments, they stop bothering. They’re not joining the discussion anymore. And that’s a pity.

Coming back to the early days of ICC, there were these very nice channels. It was a social affair with not too many people, maybe a few hundred. And it worked. As I described it in the book, it was like going to your favorite cafe and meeting your friends and having this common interest in chess. There was always chess to talk about.

JH: Before we talk about what happens when a platform gets very big, let’s talk about ICC now, because some of us have known about this for a while now, but ICC [as chessclub.com] has relaunched.

PD: I interviewed the old guys in May 2023, I think. I was with Marty [Grund], Ruy Mora, Sandro [Leonori], and Daniel Sleator, and they hinted at it. They were like, “Yeah, maybe we have something in the pipeline. We cannot talk about it.”

So I don’t discuss their relaunch at all in the book, unfortunately. But I knew that something was going to happen, and more and more people heard about it. At some point David Llada told me, “Yeah, I’ve quit FIDE and I already have another job.” It was the end of last year, maybe, and I was like, “I think he started at ICC.” And then of course, many months later, he told me that he did.

Have you been playing on the site?

JH: I tried it. I think it’s still a work in progress, but I will be curious to see what happens. As I understand it, the people behind the project, they have a lot of expertise in e-sports and e-gaming. So I’m hopeful that it’ll be another competitive platform, but of course there’s a high barrier to success.

PD: I agree. Especially for a platform that has such an amazing history ... they were the very first, so that they’re actually working on a comeback, I think it’s great. And to be honest, I think everyone at Chess.com also loves that this is happening. Because in the long run, this can only be good for the chess world.

JH: I used to write about coffee, and there was a report I read that claimed when you have a Starbucks come to town, it’s actually good for local coffee places because it brings more eyeballs and more dollars. People get into coffee, and then they branch out and say, “Oh, well, what else is there besides Starbucks”?

Having more successful platforms can’t be a bad thing. But the 800-pound gorilla for the last 10 or 15 years in the chess world is Chess.com. You have worked for and with them for many years, but you do a very even-handed job of talking about their growth, their successes, and some of the difficulties.

Tell me about these three waves of growth that Chess.com has seen in the last few years, and why you think chess in general has exploded the way it has.

PD: The first big development was, of course, the pandemic. We had moments of growth before, but it was much more gradual. And I think ... for example, a few years before the pandemic, we had quite a success with Puzzle Rush. I still think that might have been the most successful single product launch in Chess.com history, because everybody was talking about it for a few months.

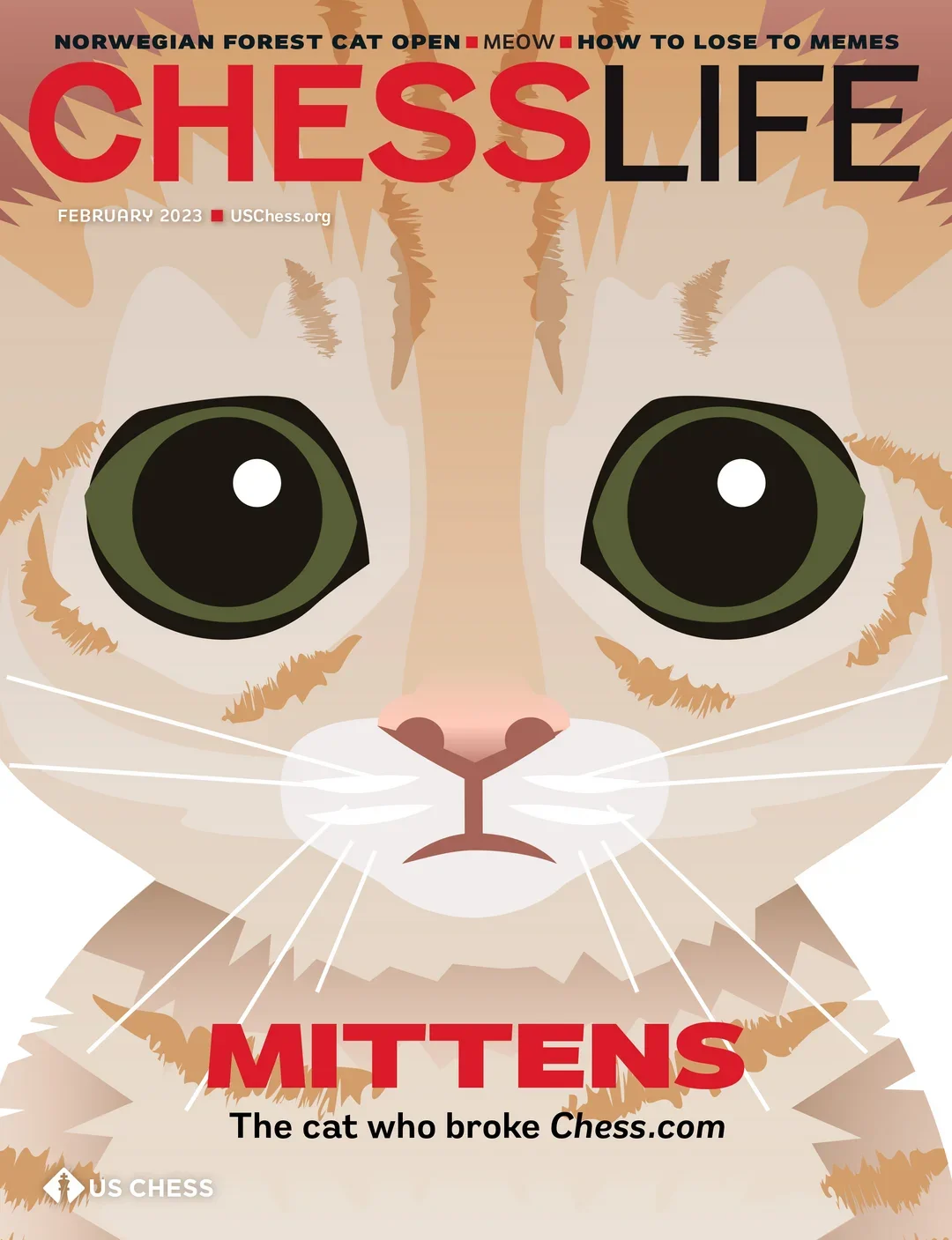

JH: Do you think it was more successful than Mittens?

PD: Later on, Mittens became an even bigger success, but I don’t really see it as a new product. It’s more like an iteration of playing against bots, which we already had.

JH: OK, back to the pandemic.

PD: We had 34 million members in March 2020. There was about half a million new members a month. And it was steady ... it had been like that for years.

And then we saw a projected growth increase for the coming three months. The numbers were astounding — it was what we expected to happen in 10 years. We understood that there was a global pandemic, that we were benefitting from it, but that kind of growth could never happen again. It was insane.

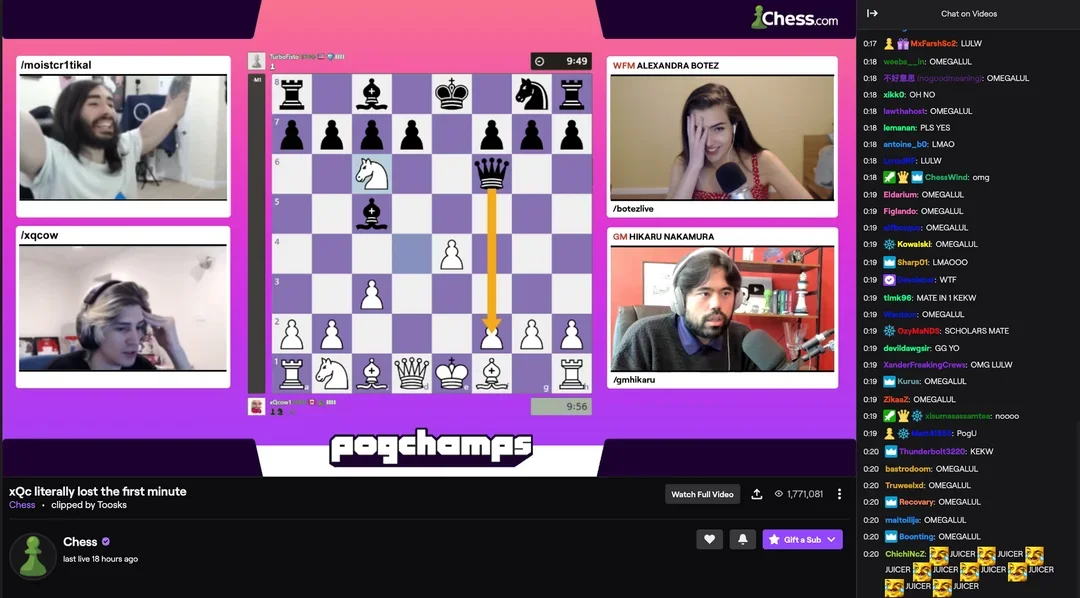

There were a lot of things going on: Magnus Carlsen launched his series of online tournaments on Chess24. We did the FIDE Online Olympiad on Chess.com, which was quite successful. And then there was PogChamps, which got a big boost from the streaming community.

But the second big wave was October ... well, the wave started in October 2020 when The Queen’s Gambit came to Netflix. A day before it launched, we had 44 million members. We had grown by 12 million in less than eight months — 1.3 million new members a month, which is three times as fast as before COVID-19.

And then a few months after The Queen’s Gambit was out, let’s say March 2021, we were already at 61 million members. We grew 3.4 million members a month. We grew six times faster than before the pandemic.

The Queen’s Gambit was a limited mini-series, and while everyone still hopes it will have a sequel, it’s pretty clear from the director that it’s not going to happen. So our conclusion was that this kind of growth would never happen again. This was the biggest period for growth, and that’s that.

And in late 2022 our numbers just skyrocketed. One of our original tech guys, Igor Grinchenko ...

JH: There’s an excellent description of him in the book.

PD: Yeah, Jay Severson described him well. It was very funny.

JH: I’ll leave it to the reader. It was incredibly memorable.

PD: Igor looked at the numbers and thought that Chess.com was being attacked — a DDoS or something, because the number of people online at the time was huge. And then he started investigating things that you can’t really manipulate, like the number of games being played on the website, how many finish in checkmates or flags ... that sort of thing. And then we realized that what we were seeing was legitimate traffic.

We had 8.9 million new registrations in both January and February of 2023. Those two months were the absolute peak of chess popularity. But still, in March 2023 we had 7.5 million new registrations, and 5.7 million in April 2023. This was all bigger growth than during the pandemic, which is crazy.

JH: What did you ultimately attribute that third wave of growth to? Was it the rise of, or the maturity of, streaming? Was it certain streamers getting traction on YouTube?

PD: I think there were multiple causes. One of them was the famous Louis Vuitton photo with Messi and Ronaldo playing chess on Instagram. It’s still one of the top 10 Instagram posts, I think, in terms of number of likes.

We had the chess boxing event run by Ludwig in December 2022, which was quite popular. You might not think it wasn’t really that big, but all this stuff gets mentioned in the mainstream media. Big newspapers were writing about it.

And the third I wanted to mention is Mittens. That ended up on CNN and I think even the New York Times. Mittens was a huge success, and when people outside the chess world are reading about it, it makes the growth even bigger.

I would say that those are three of the smaller developments in that period, but one of the very big ones is something we’ve already discussed: the Carlsen – Niemann scandal. That was a tremendous source of growth. Chess was in the news all over the world for two or three months, which ... I don’t know the last time that happened. Kasparov and Deep Blue only lasted one week, right? We have to go back to Kasparov versus Karpov to find that kind of sustained attention.

There’s this famous saying that when you get a book published, a bad review is better than no review at all. I don’t know if I want bad reviews, but I probably have them coming.

I think it’s also true about chess. We don’t want chess to be always connected to scandals. Before Carlsen and Niemann, there was Igors Rausis in the newspapers because of the toilet photo. [Rausis was using his phone to cheat while hiding in a toilet stall.]

But even if it’s a scandal, having the word “chess” mentioned along with stars like Nakamura and Magnus, and Niemann as an upcoming star ... and Elon Musk being involved, and even that TV show [It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia] with Danny DeVito doing a take on it. This really brought chess into the limelight. And I do think that it has more positive effect than negative, even when scandal is the story.

The last, and maybe the biggest reason, I think, is that it was also in late 2022 that Levy Rozman, along with a few other streamers, had his big breakthrough. By then he was already successful — I think he already was the biggest streamer, with more than a million YouTube subscribers.

Then he started to do short content. He started to do Shorts on YouTube and TikTok, and that was a massive success. His breakthrough was huge for chess as well.

And you could see the effect in the ages of the new members registering. We said that there were 8.9 million new registrations on Chess.com in January and February 2023. The largest age group was 15- to 21-year-olds. There were a lot of news articles written at the time about teenagers in high school who wouldn’t stop playing chess during their breaks. Some schools had to ban chess from devices because the kids weren’t going to class any more.

The second biggest group of new members was 21- to 25-year-olds. So it was really a new generation of enthusiastic fans. They’re the ones following YouTube Shorts and TikTok and getting hooked by these new methods. It really boosted our growth, and I’m sure that Lichess and other sites were seeing it too. It was crazy to watch it happen.

JH: Do you think that this sort of demographic shift sort of requires those of us who work in chess journalism to rethink what we’re doing? I’ll give you an example: I think we covered PogChamps, but I really had to hold my nose while I was doing it. Now I’m beginning to think maybe that was entirely the wrong attitude.

PD: Maybe it’s elitism: I really enjoy playing through Botvinnik’s games, but this generation of kids who were growing up watching TikTok, they’re not going to do that, and that’s OK.

I can imagine that there are some that don’t really get something like PogChamps. It’s hard to enjoy it, because at the end of the day, it’s chess played on a relatively low level with lots of blunders. But at the same time, you have to acknowledge that it’s very popular.

I think we should sort of try to see it as something that is added to everything else, an extra development that doesn’t necessarily need to replace anything. It’s something on top of the stories we are already doing and the events we’re already organizing.

But I think it’s also natural that guys like us who have been in the business for so long, we are not immediately ready to jump on it.

JH: As we’re speaking, I’m thinking about Kyle Chayka. He has a book called Filterworld, and he talks about the effect that algorithms have on culture and on what we see and what we hear.

I think about this in terms of what we’re seeing in terms of chess content on the internet. If you go on Twitter or X or whatever we’re supposed to call it now, a lot of chess content creators are posting these mate in twos, and it’s the same ones every single time.

It’s the Morphy mate in two. They’re doing it because it engages an audience, because it looks really hard but most people can get it if they try, and they get a lot of clicks. But it also sort of restricts what chess culture is, and how it’s presented.

PD: Yeah, I understand.

JH: And I’m wondering about this flattening effect, whether this is something that is inevitable. One of Chayka’s answers to the problem of flattening is that you need to have curators: Instead of letting Spotify choose song after song for you, you need to find someone whose playlists speak to you and follow them. The same thing is true for cultural criticism or book criticism — there’s still an important role for the critic.

And I’m wondering whether this is where we as journalists need to step up and find a way to break through the algorithm and bring different things to our audience.

Here’s an example: I posted a few tricky endgame studies on Twitter at some point, and there was no engagement. Maybe that’s because I don’t pay for Twitter, or maybe I’m just boring. I don’t know. But I guess what I’m asking is, is it incumbent on us to try to break through the noise a little bit and provide something different?

PD: I think it is part of a bigger development. We see everywhere that things are consumed in the form of short videos and memes. Whenever a video is longer than half a minute, a lot of people lose interest and click away. It’s not ideal.

It’s different if you have a channel — for example, what Agadmator is doing, I think he’s choosing a different game every time he makes a video, right? So there’s never really a repetition in that sense. And that could work, as well.

But the shorts or the TikToks where people are making the same stuff over and over, that limits things, of course, and you really wish that chess fans would learn that chess is so wide and rich that it doesn’t deserve to be like that, that social media is showing only a small part of what it is.

I like the idea of the curator. I immediately thought of ... I don’t know if you know this book by Nick Hornby, High Fidelity?

JH: Sure.

PD: It’s lovely. Early in the book this guy makes a mixtape for his girlfriend. There’s the idea that you show yourself and your character through music. Because the playlist is on a physical tape, you cannot change it. You cannot immediately move to the next song. You actually have to listen to those songs in order when you listen to that tape.

I could imagine that maybe on Spotify, it would be good if you’re open to someone forcing you to listen to a certain playlist and get to know people like that. I don’t know what would be the equivalent in chess.

JH: That’s a tough question.

Maybe a trainer would decide to pick his favorite six games and tell the student, “Well, study those six games for the coming week, and then you will understand why I like chess.” Could work, maybe.

Look, the people who are encountering chess for the first time with those TikTok videos — at the end of the day, they will probably start getting interested in playing chess. Maybe they become a member on one of the platforms, they start playing games, and as they’re getting into it, hopefully they will also encounter the learning material that’s out there.

We [at Chess.com] have a lot of classics in our video library, for example, and in our articles. We have, of course, weekly columns that still talk about ... there’s a lot of old stories. And the more you dive into things, even on Twitter, I think the younger generation will come across the older examples, the bigger culture that is behind our game, if they’re open to it. So in that sense, I don’t think they will always be only exposed to the quick checkmates and nothing else.

JH: Let me circle back to this, because in the epilogue, you talk a lot about the influence Chess.com is having. And again, you mentioned that because of your relationship with them, you may be biased, but I think you handle it very well, so I want to commend you for that. But I wonder about Chess.com really taking over the landscape — what the long-term effect is, because online chess, for better or for worse, is built for speed.

PD: Yeah.

JH: We have all of these rapid events and all of these blitz events. And the problem is, I find them utterly disposable. The one after the other, after the other — my eyes glaze over; there’s no story. It’s just someone playing someone on this day and I don’t really know why.

PD: Yeah, I know the feeling, to be honest. And I’m noticing ... we have a group for my chess club on WhatsApp, which is active with 20 members or so, and it’s funny. These are fairly strong club players, and what they’re talking about ... it’s clear that certain events are still followed more. They are more interested in the big over-the-board events, for example.

When Wijk aan Zee is happening, they talk a lot about it. Norway Chess a little bit less, of course, because it’s not in the Netherlands, but the World Championship is always very big. The Olympiad — they’re talking about the Olympiad.

I have to admit that when there were all these Magnus Carlsen tour events going on, and then later the Champions Chess Tour, all the big online events, they were clearly less popular in my small circle of friends. The exception was the recent speed chess event in Paris. I think that had had a lot to do with Hans Niemann’s participation, but they also love to see Magnus playing these high-stakes matches. I think that’s a brilliant formula for attention.

At the same time, we’re talking about a small segment of the chess community. Strong club players always find it very hard to believe that the average rating on Chess.com is like 1000 or something. Millions and millions of members are beginners, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

JH: I guess I’m curious about the effect that this is having on chess, because I think, again, you talk about how it feels like Chess.com has designs on growing beyond Chess.com, and it has cultural responsibilities that go along with that. And then I think about the Niemann Report, where algorithms used to detect online cheating were applied to over-the-board games, and look at the difficulties that caused.

PD: Yeah.

JH: I feel like we’re sort of looking at a world in which there might be tension between FIDE and Chess.com.

PD: At the moment, the relation between FIDE and Chess.com is not super. We are not in a fight or anything, but I think there are different views on certain topics.

Chess.com is doing a lot, and at the end of the day, and I really believe their absolute main goal is to just grow the game, to have more people play it and enjoy it. And if that happens, the shareholders will also be happy because we’re going to be making more money. But the main strategy is simply to grow the market and have more people enjoy playing chess. Just about everything we’re doing is aimed at that.

But I also agree, and I’m sure that Erik and Danny agree, that we also have to protect the culture that we have. Personally, I hope we will not see the end of the classical World Championship matches. That is something that, even though it might not be the most watched event, maybe we will find a format, maybe it’s speed chess or something, where TV broadcasters are going to be interested.

The Global Chess League in London this October is going to be broadcast by at least 15 TV channels. So we have already found certain formats that interest producers and channels. Maybe long games that can last five or six hours ... maybe that’s not the ideal format for TV, but I hope that chess becomes so successful that we can continue to organize them anyway, even if they don’t draw the biggest audiences.

I have written very critically about FIDE over the years, and I’m not happy with certain things that are going on there, especially related to Russia and Ukraine. But I’m excited — I’m not sure what it really means that Google is a sponsor for the Ding – Gukesh match, but the fact that they are actually working with Google, that Google is committed and allowing their name to be used and they’re actually going to be involved, that can only be good news.

This could be a game changer for FIDE, to be honest. And in the Chess.com Slack, everyone was saying, “Well, this is great. This is simply great. What they’re doing right here is awesome.” So who knows what the future holds?

JH: I’m happy to see chess grow. I just want to keep it a little bit weird. I don’t want to lose the bit of culture that is hard to commercialize or commodify, and I think that’s the tension that I’m worried about for the next few years.

PD: Yeah, I could see that.

JH: I don’t have an answer for it. And I think you’re right: The more people come into the game, the more people stay with it, the more people grow to love it, it gets bigger and bigger. I just want to keep it a little bit funky.

PD: I hope that all those different things can continue to exist alongside each other. We keep the traditional events, we add new ones, and hopefully they can coexist and grow.

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (2)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)