Editor's note: This story first appeared in the May 2024 issue of Chess Life Magazine. Consider becoming a US Chess member for more content like this — access to digital editions of both Chess Life and Chess Life Kids is a member benefit, and you can receive print editions of both magazines for a small add-on fee.

Part I – the other side of chess success

If any word were to define me, it would be “chess.” Consequently, I’ve thought a lot about what I’ve told my friends and my teachers over the years about it: how I intentionally leave out the parts I think people won’t want to hear, and why I often take for granted everything this beautiful journey across 64 squares has exposed me to.

I’m writing this article because I don’t want to continue succumbing to those impulses.

I started playing chess when I was around six years old. I wish I had understood how to improve or how to approach chess at that stage, but I didn’t. It was only my mom’s unconditional love and my dad’s unwavering support that enabled me to fail and fail again for years so I could figure things out on my own and grow.

Often, the prolonged frustration I’d feel would have me wondering if chess was actually my thing. I would put unhealthy pressure on myself to meet my standards of success, and my parents naturally had expectations for me as well. When I didn’t meet those standards, I withdrew from tournaments out of embarrassment.

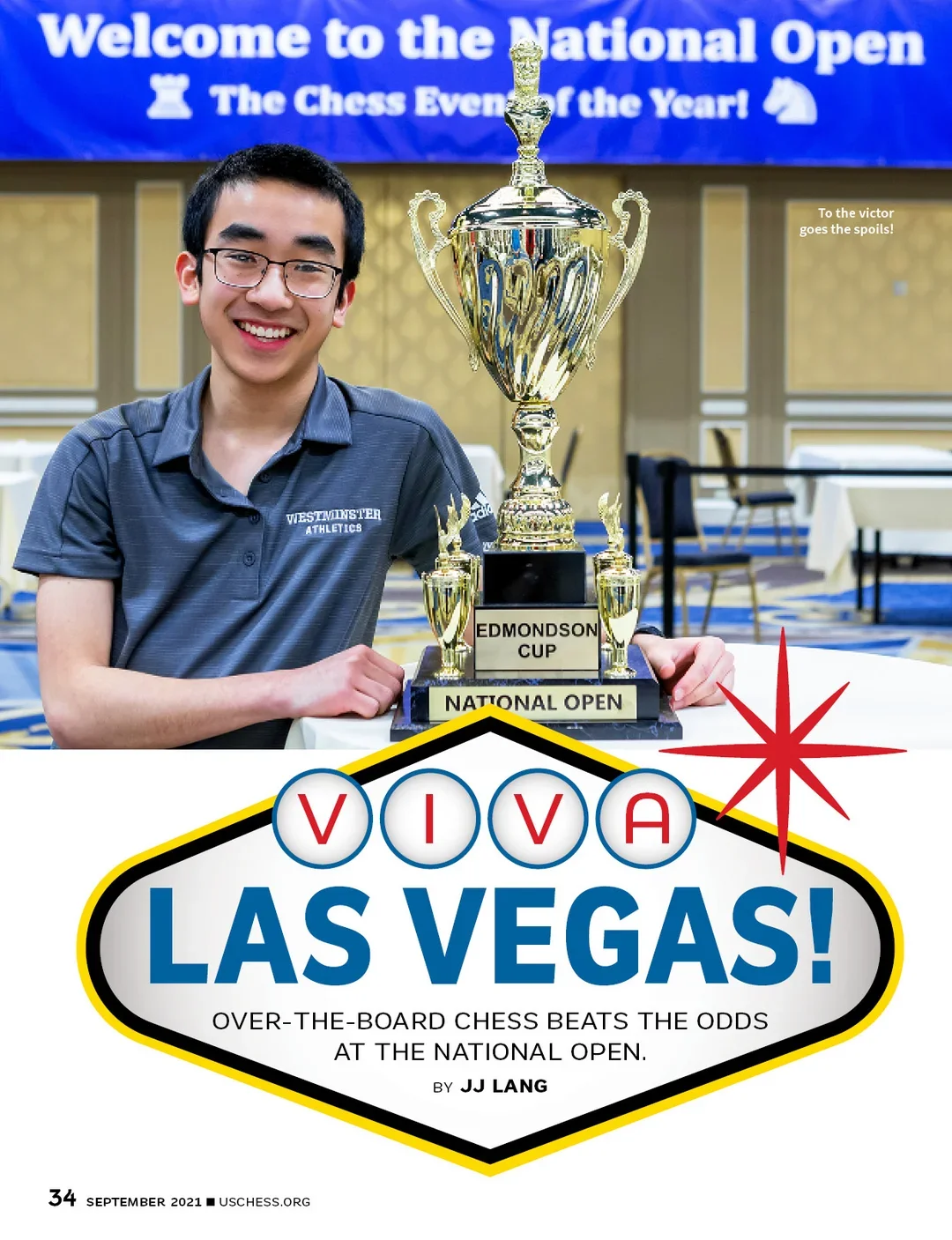

I unexpectedly won the National Open in Las Vegas in the summer of 2021, right after my freshman year of high school. I finished ahead of 22 grandmasters and earned my first grandmaster norm after three-or-so-years of zero improvement. I remember feeling relieved, thinking, “Finally! This is my breakthrough.”

But the bitter truth soon became clear: I was wrong. The following year saw some of the worst chess I’ve ever played. Between balancing AP classes and other extracurriculars, failed tournament after tournament began piling up. Chess became a nuisance, a burden. I no longer could muster anything like the same zeal and excitement as I had before.

Worse, even sitting down to study chess had become difficult. I was either too distracted and indifferent, or I made sure to procrastinate so that I didn’t have to stare at the piles of analysis. Even when I did force myself to work, I kicked the can down the road, ignoring my weaknesses and all the effort that improvement required.

I had turned my passion into labor. Even when there were bright spots in my play, light piercing through chess’ dark forest, I chose to ignore them to linger on the same fear that I would forever fall short of becoming a grandmaster. It took a toll on me. Whether I’d wanted to admit it or not, chess had finally broken me.

So I quit.

In the summer before my junior year, my dad and I agreed I should “take a break” from chess to pursue my other passions. It was supposed to be temporary, but we both knew I was giving up the game for a long while. The shame and regret I felt were unbearable — 10 years down the drain. It felt cowardly.

Yet there was a certain peace I felt in quitting. Not thinking about chess for about a year made me rethink my standards and what I enjoyed about the game. After a few months, I began to miss the adrenaline. I missed sitting down to adjust my pieces, focusing, and immersing myself in every nuance of a position for hours on end. I missed the feeling of winning and proving myself wrong. I just missed chess.

What I realized is that sometimes, stepping back is okay; I now understand that being away brought me closer to the game. As my dad and I packed my summer 2023 schedule with two and a half months of nonstop chess, I hoped for a new start and felt excited for my last shot at this GM thing before my senior year.

It was smooth sailing at first. After achieving my second and third norms in my first two tourneys in Budapest, I thought I had finally struck gold.

Then came a harsh reality check in the Rigo Janos Memorial. Coming off an abysmal collapse, and then blowing a clearly winning endgame in the previous two rounds, I was poised to strike back against an opponent who was also struggling in the tournament.

After winning my first two rounds there, I played GM Peter Prohaszka in round three. (Editor’s note: for another take on this game, check out WGM Tatev Abrahamyan’s annotations in our October 2023 article.)

The win was not clean, and I was fortunate to stay on track. A grueling five-and-a-half hour game against GM Aryan Chopra in round four, however, brought me back to my senses. Following quick comeback win in round five, the most crucial round thus far awaited me, which would set the tone for the rest of my tournament.

Getting a draw as Black against a very strong grandmaster not only grew my confidence, but it also ensured I’d get even more favorable pairings (for norm purposes) in the final rounds.

The next three rounds were considerably less stressful. Solid draws against two 2600s as White and a win as Black against a lower rated player concluded my title run with another GM norm performance.

After my dad told me I broke the 2500 rating following my last round, I expelled an impassioned “YES!!,” and felt nauseous (in a good way). How inexplicably weird to have the last dozen years of my life culminate in one singular moment.

Suddenly I realized that I didn’t even know how to celebrate. All my friends and family were thousands of miles away — all I could do was text them. I think that’s why I felt a bit empty then. I won’t forget the surreal train ride back to the hotel, looking out the window in silence, and seeing all the stations and people pass by like any other normal day, oblivious to my feeling of accomplishment.

I wish somebody had told me that becoming a grandmaster is not the End-All-Be-All and that it wouldn’t suddenly make me fulfilled. I wish somebody had told me what embarking on this chess expedition was really about.

It wasn’t about the titles or the rating gains. It was about learning from my mistakes and growing into the person I am today.

The requirements for the GM title now completed, I returned home to the States in July for the 2023 U.S. Junior Championship. There I suffered a tough loss in the final round after going in tied for first, destroying any chances for qualifying to the U.S. Championship. But then, almost as fated, I was fortunate enough to earn a perfect score (6/6) for a second consecutive win at the 2023 Denker to cap off my summer.

Chess has taught me about ups and downs, and that life goes on. Wins and losses are both natural and necessary; both must be embraced. And even quitting is okay.

Chess has made me realize how blessed I am to have found a passion while I was young and could devote everything I had to it. It’s made me appreciate all the people who have shared this journey with me. But above all, through the years I’ve spent on chess, and all the struggles to achieve my goals, I have been shown glimpses of myself I wouldn’t have seen otherwise. That’s the real gift chess has given me, and I don’t think there’s anything more important I could have learned along the way.

Part II - My Secret Sauce and Tips

Every chess player is different. Likewise, their road to improvement will be unique. But I do hope you’ll gain a bit from my experience. Here is my advice to readers.

1. What and how to study with a busy life?

Like many other full-time students, or adult players with multiple life obligations, I didn’t have the luxury of many hours a day to study chess. The truth is that on many weekdays, I didn’t even glance at a board.

If you don’t have much time, efficiency in studying is key. For me, I spent my time studying GM Magnus Carlsen’s games deeply. I would argue that all you need to become a strong player can be found there.

Carlsen’s games have no weaknesses, span all kinds of openings, and reveal the best middle-game and endgame strategies. Of course, working with annotations or books on his games can help you understand how the best player in the history of chess thinks. Look up the theories if you don’t understand certain openings, pawn structures, strategic themes, or endgames, and fire up your engines if you can’t grasp why a move is a mistake.

Study those brilliant games — or the games of your favorite elite GM — again and again. Everything you need is there.

Also: work hard and relentlessly on your weaknesses. Chess is more like a marathon than a 100-meter dash. In other words, slow and steady wins the race.

2. Playing up and playing down

I learned a lesson by always playing up in my early chess career. The truth is, I “enjoyed” playing up because it often resulted in gained rating points. But playing up doesn’t give you the pressure you will have to face in open tournaments, in which you inevitably will play players around your level or below your level. It took me a long time to overcome a sense of uneasiness when playing lower-rated players due to the fact I always played up.

This is why, if I had to start over, I would balance playing up with playing in my rating groups.

I continued to play in scholastic events, especially Nationals, even after I was already a titled player. Nationals are hard on the top seeds. A lot of kids are underrated, and they prepare with their grandmaster coaches to take the top players down. You rarely gain any rating points, and a slight miss is all you need to ruin your championship chances.

What, then, is the benefit of playing nationals? The experience of how to handle pressure. It is very stressful to sit on the top boards all the time; you’ll learn how gravity works. Fighting against it is a path to growth.

3. Coaching and learning to study on your own

I believe having someone stronger than you to discuss things with is a shortcut to improvement. If you want to reach an expert level, having at least an master-level coach is crucial; if national master is your goal, then an IM coach is needed, and so on.

However, after your US Chess rating is around 2300 or so, I think it’s possible to plow ahead on your own, especially with all the tools available today: books, annotated games, videos, online classes, and chess engines.

Good coaching is expensive, and many families can’t afford it. The ability to study on your own becomes critical. One thing I have noticed is that the desire to read chess books at a very young age often is an indication of how much you will remain truly passionate about chess later on.

I was fortunate to be among the few made the GM title before graduating high school without being homeschooled. I did it without a coach (though I briefly tried to find one), for the last six and half years, and after becoming a strong master. Progress is definitely possible, but I would be lying if I were to say that it had not been a very lonely and tough road to traverse. Extremely hard work is needed, and so is a pure mind/heart; both are more important than the often overrated “talents.”

4. Pursue other passions

Chess is wonderful, but it’s not everything. Regardless of what your coach tells you, the truth is that it’s just one of many passions, activities, or hobbies you can pursue. It’s not the magic pill for your future success, but the lessons learned from chess — like those from any other competitive sport or intellectual interest, if intensely pursued — can be very helpful.

It is okay to leave chess if you find out you may be better at something else. You will come back if you truly miss it, and then you will know chess is your thing. I would also argue that interests outside of chess may help you grow overall, helping your chess without your recognizing the benefits.

For the parents reading this article, I would refer to an old blogspot post IM Greg Shahade wrote many years ago. There he said getting to GM is very hard, and that while chess should be encouraged, it should not be forced or falsely pushed. I completely agree.

As with any time-intensive activity, excellence in chess requires years of sacrifices. The trade-off is having less time to pursue other activities, to focus on academic interests, or to spend time with friends and family.

I would argue that even if your kids choose not to continue in chess, your investment won’t be wasted. I suspect many of them will find their way back to the board again in another stage of their life, or at least, they can coach their own kids in the future!

Finally, I would like to close by thanking the people who were instrumental to my chess progress: David Vest, who got me started in a free library chess class and became my coach in my first few years playing; GM Alonso Zapata, who guided me to a rating of nearly 2300 US Chess— I was his first student when he moved to Atlanta from Colombia; IM Greg Shahade, whose US Chess School camps made me hungry to improve; and finally, GM Sam Shankland, who helped me shake off the rustiness after a long absence from chess and boosted my confidence by working with me in an intense multi-day training session.

To all of them, I’m very grateful.

Categories

Archives

- December 2025 (25)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)