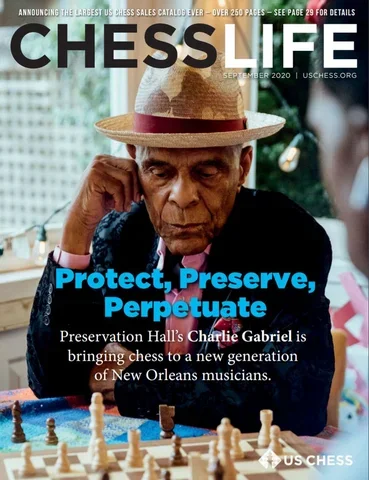

Editor's note: for only the second time in US Chess history, we are "breaking the third wall" between print and digital media and publishing our September Chess Life cover story here at CLO. Michael Tisserand's fine profile of New Orleans music legend Charlie Gabriel (IG: @chess_with_charlie) deserves to be shared with as wide an audience as possible. We are proud to bring it to the world as an example of the fine writing one will find in Chess Life.

If you like this article, consider listening to our interview with Tisserand in the September edition of "Cover Stories with Chess Life," a monthly podcast hosted by Chess Life / Chess Life Online editor John Hartmann.

Charlie Gabriel had already done quite a bit by his twentieth birthday. Born in 1932, he was a fourth-generation jazz player growing up in the jazz city of New Orleans. At 11, he joined the Eureka Brass Band and started playing his clarinet and saxophone for everything from weddings to jazz funerals. At 14, he moved to Detroit and within a couple years found work with the famed vibraphonist Lionel Hampton, where he played alongside bassist Charles Mingus. In time, he’d be touring the world in Aretha Franklin’s band.

But this wasn’t the challenge that was facing Gabriel when he turned 20. That was the year he learned how to play chess.

“My oldest brother, August, was teaching his kids how to play chess,” Gabriel remembers. “He said, ‘Charlie, let me teach you this game.’ ‘Man,’ I said, ‘I don’t have time to learn a game. I’m too busy playing this music.’”

Now 88 years old, Gabriel is speaking to me by phone from the home where he’s been quarantined with his wife for the past several months, leaving only for occasional trips like the local drug store. Despite hardships, he speaks in a voice that is equal parts whisper and laugh, and he plays though his stories of old days with unrelenting good humor.

Those initial chess lessons with his brother were more than six decades ago, but he remembers them well. From the start, he says, his nieces and nephews were tough. “They were whooping me!” he says with another laugh. But he kept at it. He never became a tournament player. He’s not one for discussing favorite openings. But ask any traditional jazz musician in New Orleans and they’ll tell you that a chess board is never far from Charlie Gabriel. “Everything I do is always involved in chess playing,” he says.

His career in music has been long and storied. In Detroit, when Motown records opened, Gabriel played with the Funk Brothers, the house band that can be heard on many of the famed studio’s greatest songs, from “My Girl” to “I Heard It Through the Grapevine.” (Session players were frequently uncredited and, as Gabriel told Geraldine Wyckoff for New Orleans’ OffBeat Magazine, he has played on so many records he can’t remember them all.)

Although living in Detroit, Gabriel kept tabs on his family and friends in New Orleans. He watched as a new institution called Preservation Hall took root in a tiny art gallery on St. Peter Street in the French Quarter. In 1960, a music-loving couple from Pennsylvania named Allan and Sandra Jaffe found their way to jazz shows being staged by the gallery owner, Larry Borenstein. Enraptured by what they heard, they moved to New Orleans and Preservation Hall was born. In addition to providing a rare venue for older traditional jazz players, Preservation Hall also became one of the few clubs in the South that openly featured racially integrated bands. The Jaffes defied both Jim Crow laws and entrenched customs, even shaking off occasional threats of violence. Now in the hands of their son, tuba player Ben Jaffe, Preservation Hall has become a landmark for music-loving visitors and locals alike, with touring bands bringing its sound around the world.

Speaking to Wyckoff last year on the occasion of winning OffBeat’s Lifetime Achievement in Music award, Gabriel recalled the day he knew he had to return to New Orleans: August 29, 2005. “When Katrina hit New Orleans I was watching it on TV and I was crying like a baby,” he said. “It just blew me off my feet. I always knew I was going to come back home and spend my last years playing music in New Orleans.”

Thanks to Preservation Hall, he had a musical home to return to. When Ben Jaffe heard that Gabriel was looking to return to New Orleans, he eagerly brought him into the fold. That’s also when Jaffe learned he was also bringing chess to Preservation Hall.

There’s a long and distinguished history of jazz musicians and chess. Drummer Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers paid tribute to the game in Blakey’s tune “The Chess Players.” Trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie was an avid player, known to have played matches against everyone from saxophonist Charlie Parker to Billie Holiday to Ray Charles. And thanks to Charlie Gabriel, chess is now woven into the fabric of traditional jazz in New Orleans.

“When I came back home, nobody in the band was playing chess, none of them,” Gabriel says. “So I started showing them moves, showing them how to get out of situations. Every move has a counter-move. You got to look for that counter-move to win.

“Ben Jaffe, whoever wanted to learn, I taught them. Kyle Roussel the piano player, he fell in love with it.” Gabriel laughs again. “I’m still the best in the band, but that’s not saying much.”

“It’s a chance for us to leave the world behind for a couple hours and meditate on the next move,” Ben Jaffe says of his chess dates with Gabriel. “I’ve played Charlie hundreds of times and the only times I’ve beaten him are when he gives me every move!”

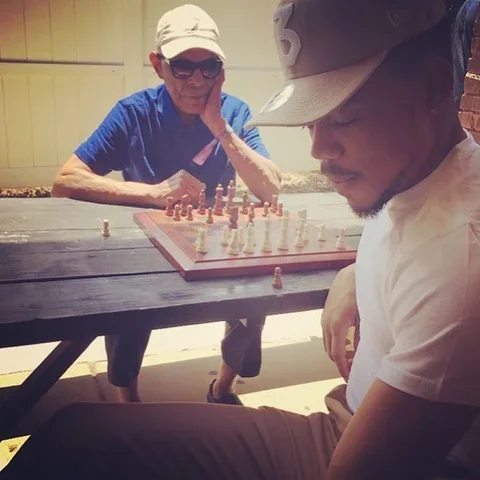

Gabriel’s home is a chess shrine, with ornate sets given to him by fans from around the world, including one so heavy that Gabriel says he can’t lift it. His Instagram account, titled “Chess With Charlie,” is as devoted to the game as it is to jazz. When Gabriel tours, he always packs along at least one set. When the Preservation Hall Jazz Band appeared at the Bonnaroo Music and Arts Festival in Tennessee, Gabriel set up a game backstage and went head-to-head against Jon Batiste, the bandleader of The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, who grew up playing chess in New Orleans. When musician Chancelor Bennet —who performs as Chance the Rapper — came across the games, he eagerly joined in as well.

One New Orleans musician whom Gabriel is still waiting to play is trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, an avid chess player whom Gabriel has known since Marsalis was a child. “I hope I have the opportunity to play a chess game with Wynton before I close my eyes,” Gabriel says with a quieter laugh.

In New Orleans, one of Gabriel’s favorite sparring partners is German-born saxophone player Martin Krusche, who leads the brass band Magnetic Ear. Before the quarantine, the two would regularly get together for games. It started casually enough but quickly grew competitive. “Chess drew Charlie to me because he usually doesn’t lose many games, but with me he will,” Krusche says. “The first few months, he didn’t win a game. Then he became much stronger.”

More recently, the wins and losses have started to even out a little more. It’s hard to prepare against Gabriel; you just have to stay alert to the game. “Charlie’s a rather open and adventurous player. He’s not predictable, not by the book,” Krusche says.

Gabriel says he welcomes a good loss. “I don’t want to be whipped, but I don’t mind being whipped,” he says. In 2015, he joined the Preservation Hall band on a trip to Cuba that was memorialized in the documentary A Tuba to Cuba. They came across an older man in a park who was playing chess. Gabriel doesn’t recall his name, but he still remembers the games. “That old guy beat the hell out of me,” he says. “I enjoyed it though. You never lose, you never learn.”

Other, more difficult, losses for both Gabriel and Preservation Hall have been mounting this year, as they have for all musicians and music clubs. Preservation Hall has been shuttered. On June 20, the club responded with a live-stream benefit titled “‘Round Midnight Preserves” to raise money to assist musicians. Special guests included Paul McCartney, Elvis Costello, and Dave Matthews.

A highlight of the online concert was a Zoom-style video of Gabriel’s song “Come With Me.” Gabriel first wrote the lyrics when he was trying to convince his then-fiancée Marsha to join him in his home city. It’s a jaunty tune filled with promises of good times. For this performance, Dave Grohl of the Foo Fighters joined Gabriel on vocals:

It’s a song about the kind of night you could once easily find by strolling through the doors of Preservation Hall, but it’s now made more poignant because packing into an intimate jazz club will certainly be impossible for the foreseeable future. For the time being, both Preservation Hall and Charlie Gabriel are still searching for the best counter-move.

Gabriel, meanwhile, is also trying to get his chess game started again. Unaccustomed to playing online, he tried setting up a board and playing with Krusche via telephone, but didn’t find it satisfying. Krusche has promised him he’s going to find a way to get him on the internet, and that when he gets there, there will be plenty of games waiting for him.

Gabriel is eager for that day. “Chess has a lot to do with how you feel as a person,” he says. “Chess is medicine, it keeps you healthy. All the beautiful things I know that I achieved, chess had a part of it."

Categories

Archives

- December 2025 (24)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)