Editor's note: with this publication of GM Jesse Kraai's cover story for the June issue of Chess Life here at CLO, we are "breaking the third wall" between print and digital media for the first time. Kraai's thoughtful consideration of what it means to play chess in the time of COVID-19, and what it might mean for the future of chess, deserves to be shared with as wide an audience as possible. We are proud to bring it to the world as an example of the fine writing one will find in Chess Life.

If you are not currently a US Chess member, please consider becoming one (or renewing your membership!) to support all of our publications and the mission of US Chess: to empower people, enrich lives, and enhance communities through chess. ~JH For those who would prefer to listen to GM Kraai's "audiobook" version of this article, we have made it available at our YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GloQu2yfJ2k You can also check out the June episode of Cover Stories with Chess Life, where Chess Life editor John Hartmann interviews Kraai about his article, his life in chess, and his thoughts on the future.

Chess and Coronavirus

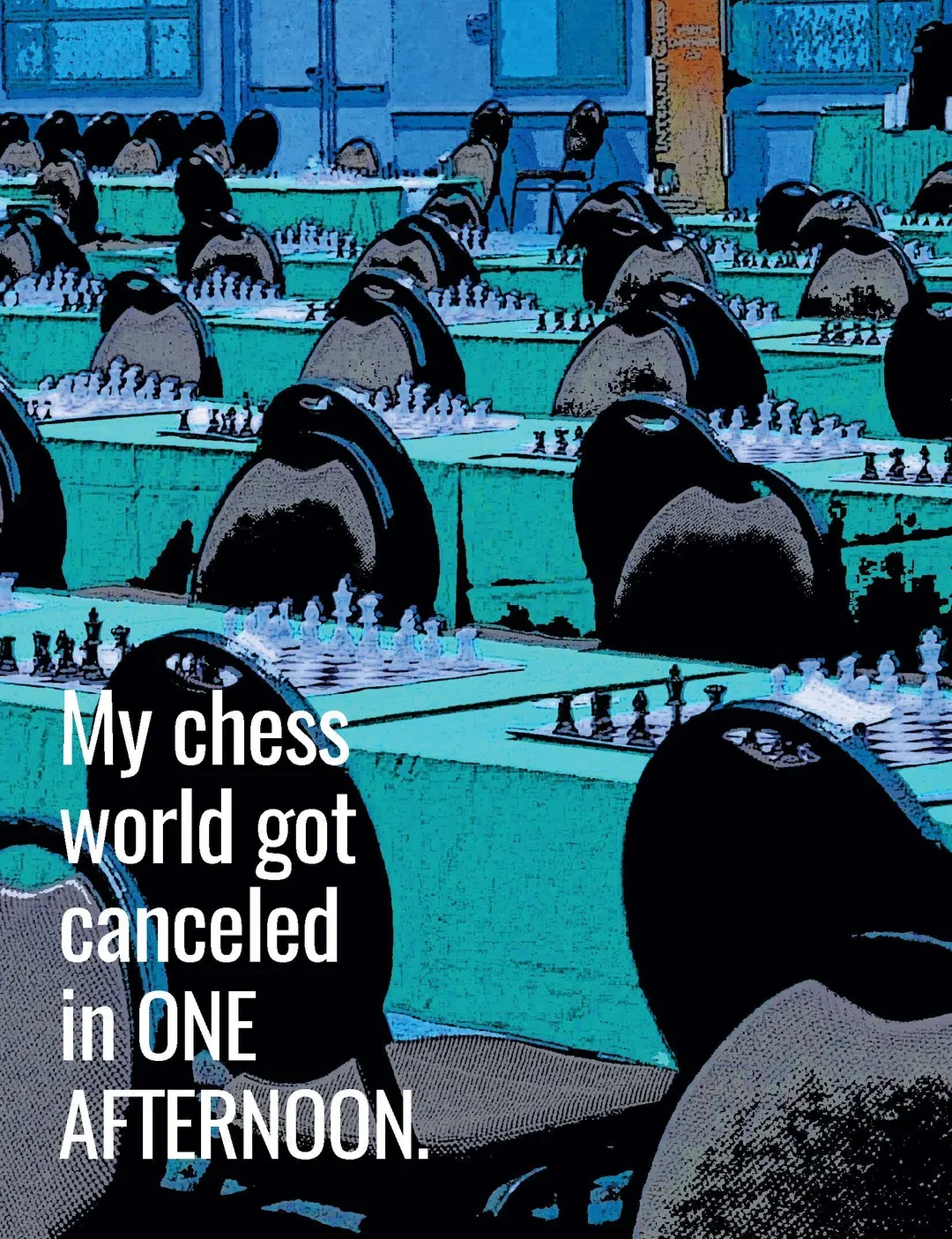

My chess world got canceled in one afternoon. My trip to the Saint Louis Chess Club to be their resident grandmaster was canceled. The Denver Open was canceled. My kids’ daycare was canceled. And several promising students canceled, saying they could no longer afford lessons. For several months I had been trying to make a comeback. I wasn’t going to ever be world champion or anything, but if I could get my rating back over 2500, maybe the Saint Louis Chess Club would invite me to play in one of their events. And maybe in a couple years I could qualify for the U.S. Senior Championship and even dream of playing for the U.S. senior team. With one round a day and a social distance of at least four feet from the next board, the calm dignity of tournaments like those is the closest I’ve come to being part of a spiritual gathering. But to get back to that promised land I’d need the 2500. And getting back to 2500 would mean playing in weekend Swiss tournaments until I had planted my flag on the corpses of 60 ten-year-olds with a Puzzle Rush score over 40. It’s hard to imagine the usual American weekend Swiss not getting canceled, at least as we knew it. The transmission of bacteria and viruses begins with a cordial handshake before the first round on Friday night. Then they start breeding. Our lack of sleep and the anxiety of battle helps them crawl into us. Every male chess player has smelled the microbial world when they run from their board for a nervous pee and open the moist bathroom door. By the Sunday rounds the potty is a sulfurous purgatory. Every male chess player has seen the scraps of toilet paper stomped into a floating debris, the shoeprints on the toilet bowl, the brown paper towels flowing out from the bin onto the floor like lava. So yes, dear friends, our tournaments have been a dance hall for all the little things that feed on our skin, gut, and lungs. We obviously share more than just the game. But let’s move on.

Dinner with Kasparov

Imagine a darkly lit cavernous room with older Italian gentlemen pouring you wine so smooth it wears a sweater. Earlier that evening I stepped off the plane to get a text from Joy Bray, the general manager of the World Chess Hall of Fame in St. Louis: “Would you like to have dinner with Kasparov?” Boy howdy, yes I would. “Great, pick you up in one hour.” There were about eight of us around a large circular table and at some point Joy asked us what we thought of the newer and faster time controls. Well, listen to my rant: I am opposed. The beauty of chess is found in the depth of its moves and strategic conceptions. Chess fans want to sense the sublime when they experience a game. And the reason the World Championship is so popular beyond the chess world is because it’s a proxy for the questions, “Who’s the smartest?” and “What does smart look like?” If we make the game any faster we will cheapen it into a video game. We will make chess an esport. Many answers were given on both sides of the argument. Kasparov spoke last. He said something like, “Look, everyone is making emotional arguments based on their personal connection to the game. But the trend is obvious. Chess is getting faster.”

My fight with Greg

You might know my worthy foe as “the brother of Jen Shahade” or simply “The Lesser Shahade.” But behind the scenes, IM Greg Shahade has guided at least two commendable projects. He founded the U.S. Chess School, which has been elevating the game of our most talented youth for years. And he started the U.S. Chess League, the first online team event, which has since evolved into the PRO Chess League. My dispute with Greg started long before I realized I was on the wrong side of Kasparov’s trend. Greg wants chess to be faster. He wants blunders and commentators screaming stuff like, “Man down, MAN DOWN, better get the medics out here quick!” and, “Oh no, OH NO, dude is gonna fly off the top rope! This one’s gonna hurt.” Now, please note, when Greg and I argue with each other we couch our arguments in the context of how we can make chess more popular. As if we were in an existential battle, we find ourselves saying things like, “If we don’t get faster, we will die.” But look, we are both fooling ourselves: when Greg and I argue, I think we are actually sublimating our most intimate moments in chess. Greg came up playing blitz, a jocular blitz in parks and online. That’s how he got good, and that’s what he’s good at. He is my enemy. My chess study involves taking a scoresheet of a long game I’ve played against someone strong and analyzing that thing for days in a handwritten notebook with a nice wooden set. I enjoy thinking about how a shift in pawn structure shifts the careers of each piece, some becoming unemployed, others finding themselves suddenly the head of a promising new startup. I enjoy solving studies that take hours to solve. Greg is working tirelessly to undermine the spiritual wonder and solitude of that work.

Thinking fast and thinking slow

That is the title of a weighty tome by the Israeli psychologist Daniel Kahneman. You can read a more accessible take by Michael Lewis, the guy who wrote The Big Short, called The Undoing Project. But let me give you my layman’s understanding of Kahneman’s thinking and how it relates to chess: Your body has two kinds of muscles, slow twitch and fast twitch. You need the slow ones to do construction work all day and to run a marathon. You need the fast ones to do a bench press and run a sprint. Chess isn’t any different. You’ve got the instant and intuitive reactions of a blitz game and the deep thinking of a five-hour game. And Kahneman wants to say that they are two different games. A blitz player like Greg often experiences moments where he feels like he is “in a groove” and is somehow making all the right moves—as if he understands what is going on in the position. That optimistic euphoria is the hallmark of thinking fast and we have all felt it, both in chess and our daily lives. We need that false overconfidence to overcome the massive uncertainty inherent in all the little decisions that we have to make every day. Simply put, our species could not exist without fooling ourselves into thinking that we knew what was going on. Kahneman’s articulation of what fast thinking is opened my eyes to what I’d sensed in blitz for decades: in a blitz game you are not seeing the situation as anything new or unique, you are using a rough and tumble summation of all your past experiences to quickly make a decision. So the moves you play in a blitz game are actually the moves you’ve played before. When you are playing fast you are only looking for the things you already know. And yet every player who has spent some time analyzing a position knows that there are an entire host of unknown factors and variations that they don’t yet know and don’t even have a vocabulary for. That’s what thinking slow is for. But thinking slow is harder, much harder. A recent study found that guys like GM Fabiano Caruana burn up to 6,000 calories a day sitting at the board, three times more than your average person. And I can report to my shame that even though I preach a lot about how you should study your own games in a notebook, there have been numerous times in which I have not found the spiritual energy to do it. Just starting the process is the hardest part. And I can report that very few of my students have been able to study their own games in depth as part of their chess habits. When chess players self-report that they are lazy, what they are actually saying is that thinking long is hard. Getting punched by coronavirus forced me to think fast. It’s been hard to hold a thought. Instead I’m constantly updating my browser to see the latest epidemic numbers. Twitter tells me things all the time. And I see it in my students too; like me, the chess they do can only be fast, stuff like Puzzle Rush and blitz. It’s a pastime, a way to not face what’s going on. We are all getting a taste of Greg’s world of distraction. Now here is an experiment I know many of you have already tried. Set up an online game on your favorite chess server using a classical time control, say game in 90 with a 30 second increment. Use your nice wooden pieces if you want. Can you think in the same way as your non-online self? I can’t. My mind wanders. And I have to check Twitter and the news if my opponent really starts thinking. My students report the same experience. So let’s say something simple and obvious: the trend toward faster chess, which existed long before coronavirus, will be magnified by the move to online chess that the virus has forced upon us. And that means I have to admit I am losing to Greg. COVID-19 has greatly aided my enemy; I’ve gone from clearly worse to losing. Because online chess is fast chess. Now a thought experiment. Chess players are very proud of their ratings. Ask yourself: Which is the real rating: the online rating or the over-the-board rating? A month ago, most of us would have said that only the over-the-board rating counted. And that online ratings were like a shadow of the over-the-board proving ground. But without an active currency others will emerge. And I have to report that even before COVID-19 several strong players, as high as what I’d consider 1900, approached me for lessons and it became clear that they’d never even played an over-the-board game! These are players with a tactical awareness, a well-oiled opening repertoire, and even a rudimentary endgame understanding. So here is a simple prediction: the longer COVID-19 lasts the more online chess will come to be seen as the “real” chess.

Cheating

Online chess has historically not been taken seriously because of cheating. It’s a stigma. But cheating online isn’t as easy as it used to be. Not too long ago, cheating claims would be mediated by a weak grandmaster like myself who would somehow try to divine if something looked suspicious. But now the big sites like chess.com are developing sophisticated algorithms to catch the cheaters. And what the cheaters soon realize is that the danger is not having some chump like me look at just one of their games. They have to fear that the algorithms are going to comb through all of their moves. Last year I had a chance to talk about the situation with chess.com’s main man, IM Danny Rensch. And he told me about their small anti-cheating army. The scale of smart minds and resources dedicated to fighting the problem astonished me. It was like being invited to the other side of the matrix. And Danny told me there was a list—a list of all the cheaters they had caught. He said it was long. I’d have to sign a non-disclosure agreement to see it. I can tell you this about cheaters, both online and over the board: like the carriers of the coronavirus they are all around you, they seem honest and normal, and a surprising number of them are your friends. I knew the most famous cheater of all. He was a gentle soul who lived for chess. We played on the same Bundesliga team in the last millennium. It was that same gentle dude, GM Igors Rausis, who systematically visited his phone—taped to the toilet roll case in the bathroom stall—during his games’ critical moments. And he did it for years. Knowing Igors made me decide against seeing Danny’s list. I didn’t want to know. This is how I think it’s going to play out: Danny and chess.com have played nice guy so far. They don’t accuse the cheaters openly, because lawsuits have no upside for chess.com or similar sites. But the more online chess becomes real chess, the more severe the punishment against cheating will become, and Danny’s anti-cheating squad is only growing in sophistication.

Information Theory

Before we move on to the future I want to talk a little about the past. The history of thought is usually presented as a history of thinkers. But for the sake of our current situation in chess, let’s mention that there is a different and powerful way of reflecting on what thinking is and how it develops. Instead of saying that Luther brought about the Reformation you can instead say that the printing press caused it. Or, to put it all in a general formula: that the small and large revolutions in how we think, do business, and even worship all come from how our information is processed and distributed. In this view, my intimate relationship with chess—as something you do with a notebook and talk about with symbols like ∞, ±, and ʘ—is an outdated and dying art, even if it is still my place of worship. Greg, on the other hand, is a little younger than I and has his own set of symbols, tools, and formative experiences. But the very young players don’t even know about chess books. More than one of them has told me that books simply “are not user-friendly.” COVID-19 has accelerated the transition of our game to an online experience. Chess.com reports a 40-100% jump in the metrics of traffic, social interaction, and games played since the crisis began. And they just had nine million games played in one day. Chess will become a new thing online. And the young, who have grown up entirely online, will shape it most.

What will chess look like

First we will have a period of mourning. Old codgers like me will wail their lamentations from the sidelines, moaning about their long thoughts, their mildewy chess notebooks, and their loss of a handshake. But I’m just some guy who’s good at complaining. Consider Fabi’s plight: that kid hasn’t gone a month without a classical tournament in over 20 years. His whole life has been constructed around the struggle. And he will now certainly go through a period of what medical people call withdrawal. The moaning can’t last forever. And I already know that I can’t stop playing. I’m old enough to have tried several times before. The quitting never sticks. From that personal experience I know there are millions of other players across the world who will grasp at new ways of playing the game. And online will be the only place for chess for at least a while. International Master David Pruess told me that we are all just going to throw stuff at the wall until it sticks. And loads of sites around the world are doing just that. David and IM Kostya Kavutskiy got me involved with a site called ChessDojo and I think we are just as confused as everyone else. Take our name as an obvious example. What is it that we are training for? It sounds like we are still talking about handshakes and scoresheets. But the reality is that we are in Greg’s world now. The first week of Dojo was all about clutching onto the past with the weapons of the young: we did Twitch streams and YouTube videos about the 2020 Candidates tournament. And that was lovely. It doesn’t get much better than thinking along with the top players in the world in real time while jacked up on morning caffeine. But then that light went, and it’s not clear when or how the Candidates tournament can be rebooted. We just played a Vote Chess game against a group of players called ChesspatzerUK. Yes, it was hard to calculate and think deeply while being online—and that is our official excuse for losing the game to a proud group of patzers. But Vote Chess was also new and fun. Hearing other peoples’ thoughts as you play is certainly part of the new chess experience. And of course, you can’t complain too much about a world where you can watch and even interact with some of the world’s strongest players as they play and stream over Twitch. Dojo will soon have team events against other sites. And we will train for those events over Twitch and our Discord server. How we train and what kind of event we are training for is obviously totally unclear, something we will have to figure out as we go along. Maybe we can follow the lead of San Francisco’s Mechanics’ Institute and the Charlotte Chess Center & Scholastic Academy, who are hosting training camps online. It seems strange when you look at it from where chess used to be, when teams were all bound to some physical location. Now it starts to feel natural that a team can come from all over the world, that your sense of belonging can come from interactions with people you’ve never met in real life. For my part I will continue my long struggle with Greg. I will hack out some small corner of the world where he can’t find me, and where chess can still be played long.

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (2)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)