Editor’s note: US Chess was saddened to learn of the death of Arthur Feuerstein at the age of 86. We could think of nothing better to honor this great player from America’s past than by reprinting Al Lawrence’s magisterial account of Feuerstein’s life, near-death, and rebirth as found in the January 2012 issue of Chess Life. (Thanks, Al.)

We extend our sincere condolences to Alice Feuerstein and the entire Feuerstein family.

Tenacious: The chess life of Arthur Feuerstein is a story of promise, tragedy, and rejuvenation.

by Al Lawrence

Chess Life, January 2012

It was a rainy day but full of getaway-anticipation. Arthur Feuerstein and his wife Alice left work behind and headed west in their Dodge from their house in River Vale, New Jersey, toward their vacation home in the Pocono Mountains of Pennsylvania. Alice sat in the back seat with their beagle Daisy. Behind the wheel, Arthur looked forward to a relaxing weekend and had good reasons to feel satisfied with life in general. He had, at just 37, already risen to the top of his profession, about to be sent to Belgium to head up the European division of Sun Chemical. He was married to the beautiful girl he had fallen in love with as a student. And in the world of chess, the other love of his life, he was a leading player.

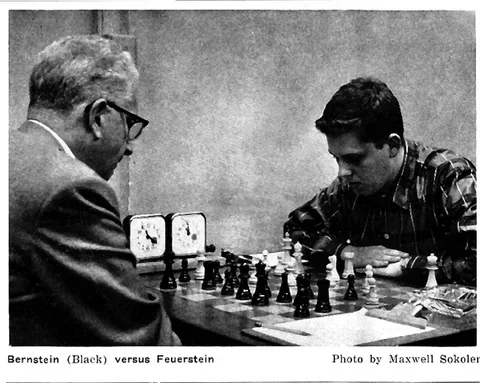

It was true that he had decided against turning pro after a very promising start as a youngster, including a solid result in the 1958 U.S. Championship. But even as an “amateur,” he had won the 1971 championship of New York City’s vaunted Manhattan Chess Club, and competed in the 1972 U.S. Invitational Championship, chalking up a draw against powerful GM Pal Benko and a win against the legendary Al Horowitz. Art could boast an even career record against Bobby Fischer, the man who had just rewritten the record books on his way to the world championship throne.

As Feuerstein drove that day in 1973 near Fort Lee, New Jersey, on a two-lane stretch of Route 46 just across the Hudson River from Manhattan, the site of his many chess victories, the driver of an oncoming 18-wheeler was going too fast. He locked his brakes to avoid running into the back of the car in front of him. Suddenly the truck shimmied precariously and jackknifed slightly, the front of its trailer angling out into the oncoming lane — Feuerstein’s lane. Faster even than the 1960 U.S. Blitz Champion could analyze and react, the trailer caught his car at the roofline, tearing off its top like foil from a popcorn tray. Something smashed into his head and then sped past him through to the back seat, where it reached so far toward Alice that it killed poor Daisy, who was resting in her lap. Alice’s back was broken in the accident. Arthur slipped quickly into a coma.

Twenty-two years earlier, as a 14-year-old student at Taft Grand Concourse High School, Art had learned chess to play with his older brother. “Harry came home from the service in World War II,” Art said, “and while he was going to college, his friends came over to play chess with him. I wanted to get closer to my brother, who was 16 years older, so I watched the game and learned chess from him.” The game captured young Art en prise. He quickly organized a chess club at Taft, playing first board during challenge-matches against other schools. “I found out that Bronx Science was supposed to be the best,” he said, “so I challenged them, and also Stuyvesant.” Art joined the Marshall Chess Club for a year. “But later someone told me that Manhattan Club was stronger,” he remembered with a laugh, “so I joined it instead.”

Inspired by a rare moment in chess history

After graduating from Taft in 1953, Feuerstein (FYOOR-steen) went on to the school of business at Baruch College, City University of New York. He continued to play chess and improve his game. “Horowitz’s and Reinfeld’s book How to Think Ahead in Chess really helped me with the openings,” he said. “I started playing the Stonewall as White.” It was an exciting era to be an up-and-coming chess player in New York City. In 1954, the Soviet team, led by Smyslov (who had just drawn an “unsuccessful” title-challenge match) substituting for world champion Botvinnik, visited America for the first and only time to play a third post-war match with the U.S. (The first match, in 1945, was played by radio; the second and fourth matches — in 1946 and 1955 — were played in Moscow.)

The match generated excitement about chess and guarded curiosity about the Soviets. The impact and historical importance of the Soviet visit can only really be appreciated in the context of America’s then-ongoing great Cold War fear and self-examination. At the time of the match, schoolchildren like me regularly rehearsed “duck and cover”—the act of crouching under your wooden school desk in the event of nuclear attack by the only other atomic power, the U.S.S.R. A national debate raged over the value of McCarthyism and its focus on even long-past associations with communism, which populated the notorious “blacklist” — names of U.S. citizens who thus became unemployable, many for decades. In fact, the televised McCarthy-Army hearings, which gripped and divided the nation with its impassioned outbursts, were concluding even as the hushed chess match began.

Treasured in Feuerstein’s scrapbook, among yellowed newspaper clippings of the era that headline his name, is a letter from the organizers of the USA-USSR match, thanking Art for working one of the giant wallboards at the event. “I remember being excited to be a wallboard-attendant,” Arthur told me. What young and ambitious player wouldn’t be? After all, he was in the room with the greatest players of the generation. Although the Soviets hammered-and-sickled the U.S. 20-12, the resulting effort to better fund the development of American chess helped to create the three “Lessing Julius Rosenwald Trophy Tournaments,” the last of which would in a few years provide a platform for a surprising Feuerstein debut.

From wallboards to the Rosenwald

Two months after mirroring the moves of the USA-USSR match on the wallboards, Arthur himself played a game against Erich Marchand at the 1954 New York State Championship in Binghamton that was widely admired for its tactical daring. The game, in which he gave up his queen for three pieces, was reported on in both local newspapers and in Chess Life, which described it as “a game of remarkable depth and beauty, earning for [Feuerstein] the first brilliancy prize.”

By 1956, Feuerstein placed only a half-point out of first place in the Greater New York Open, behind Bill Lombardy and Ariel Mengarini. Art even beat young Fischer, who finished a half-point behind him. Feuerstein was favored to win the 1956 Junior Championship in Philadelphia, but finished tied for second after drawing his individual game with Fischer, who won the event. Yet, at the city’s Mercantile Chess Club, Art won the U.S. Junior Blitz Championship, again drawing his individual game with Bobby, who finished second, followed by Lombardy.

From 1936 through 1948, USCF held the U.S. Championship round-robin tournament, dominated by Samuel Reshevsky, every two years. But then FIDE took control of the world championship on a three-year cycle. So, for a time — 1951, 1954, and 1957-8 —, the U.S. title tournament was held only during the years the U.S. needed to produce a zonal winner. Thus, in the ‘50s, there were reduced chances for Americans to compete at the top level. But the American Chess Foundation helped to fill the void by sponsoring three powerhouse round-robins—the Rosenwald Tournaments—between December 1954 and October of 1956. The third and final Rosenwald was played at both the Manhattan and Marshall Chess Clubs and directed by Hans Kmoch. Reshevsky — trying out his brand-new David-Niven- mustache — won the event in strong form, with nine out of 11, ahead of Arthur Bisguier with 7. But a whiskerless 20-year-old named Feuerstein was the surprise third-place finisher in the 12-man invitational. He drew Reshevsky, Bisguier and Fischer (who finished eighth but played “The Game of the Century” against Donald Byrne) and scored five wins to finish with 6½.

Climbing the rating ladder and falling in love

Readers of chess publications began often to see Feuerstein’s play praised. Dr. Harold Sussman wrote: “He showed splendid tactical finesse under pressure and pressed Reshevsky for the lead in the early rounds. Had he not weakened in a favorable game against Mednis, he would have finished second. … We need more training tournaments like the Rosenwald to develop our young players like Fischer [and] Feuerstein …” Annotating their encounter in the Manhattan Chess Club Championship in the April 20, 1956 Chess Life, Bisguier wrote that “the younger Arthur displays a tactical resourcefulness and tenacity which seem destined to place him among our leading players for many years to come.”

Art’s climb up the rating ladder was quick. In USCF’s May, 1956 rating list, Feuerstein was listed as a high expert, at 2150. By the spring, 1957, he was one of 60 on the master list, printed beneath 14 senior masters and one grandmaster (Reshevsky). One year later, he was a senior master, ranked 12th overall.

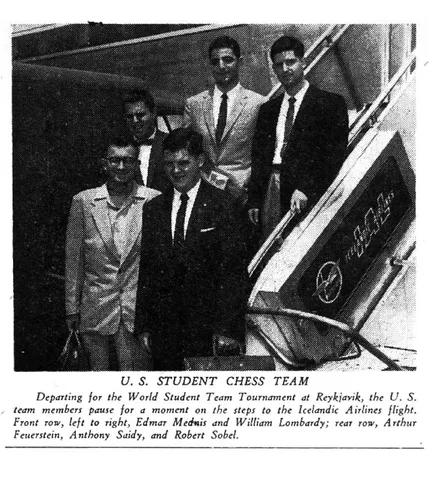

In 1957 Art was selected for the team to represent the USA at the fourth World Student Team Championship in Reykjavik, Iceland, where he played third board behind Bill Lombardy, already an IM (and who that year won the World Junior Championship with a perfect score), and Edmar Mednis, and ahead of Anthony Saidy and reserve Robert Sobel. Feuerstein finished his first international event with a respectable 50 percent as the U.S. team finished fifth out of 14. The USSR was first. The next year at the Student Team in Varna, Bulgaria, Feuerstein, with the same teammates, finished sixth out of 16, the Soviets winning again. Art and Saidy, switching boards that year, both finished with an impressive winning percentage of 67 percent.

But Feuerstein, Saidy, and Mednis were competing at the seaside resort for more than mere checkmates. In Varna, all three were captivated by the beautiful, 17-year-old Alice Rapprich, a physician’s daughter on vacation from her hometown of Prague before beginning her own study of medicine. All three young Americans played their games until late afternoon, then would go out for evenings of dancing and walks. “My traveling friend was ill and told me to go ahead and go to the dance. I was sitting at a table alone when I saw both these two Americans—Feuerstein and Mednis—get up and make a dash for me,” Alice remembered with a laugh. She put them off, but Art was persistent. Ten days later, he spotted Alice walking on the beach. He took her to see the opera Aida. “After that, I hung out at times with the team and their friends,” Alice said. “Many women had eyes for Saidy—he was gorgeous. But Arty was so funny! He always made me laugh.” Returning home to the U.S., the team members wrote Alice letters. Feuerstein, as we’ll see, however, was once again to prove the “tenacity” Bisguier had praised.

In December of 1957 and January of 1958, Feuerstein, now 23, got his first chance to play in a U.S. Championship, placing equal sixth among 14 of the country’s best masters. He finished tied with Edmar Mednis and former champion Arnold Denker — and ahead of defending champ Bisguier. Along the way, he beat James Sherwin, Hans Berliner, Denker, and Herbert Seidman. A 14-year-old Bobby Fischer won the event, beginning his run of eight championship victories.

Because of his good sportsmanship, Feuerstein secured an interesting place in Fischer-trivia. Bobby’s victory against Feuerstein was played some two weeks before the opening round of the event so that Bobby could take his exams at Erasmus High — so it was Fischer’s very first win in the U.S. Championship. Bobby then went on to triumph in all eight events he played in. To Feuerstein’s credit, Fischer’s victory in their last game together only evened their score.

Serving his country, with a special request

Later in 1958, Art joined the army. But he made sure to request a stint in Europe. He had been writing Alice! Assigned to Munich, he went to visit Alice in Prague. He hadn’t been the only member of the student team to do so. Saidy met her family there when he was shopping for a microscope for medical school. Alice recalls her mother’s advice, given in Prague when the young girl had received two letters from America on the same day — both with photos enclosed—one from a suave-looking Saidy and one from Feuerstein, who was topped off with an unflattering GI buzz-cut. “My mother looked at them both, and told me to go with THAT one!” she laughed, gesturing at Art more than 50 years later in the couple’s elegant home in Mahwah, New Jersey.

Alice and Arthur were married in 1960. “I had to get special permission,” Art said, “since Czechoslovakia was a communist country!” The same year, Art also found time to win the very first U.S. Armed Forces Championship. Art was soon transferred to a dream assignment in Paris, where the couple lived much like civilians and enjoyed what seemed an extended honeymoon. In fact, Art had to get into uniform only to pick up his paycheck once a month. They roamed the romantic streets of the Left Bank together. He frequented the legendary Club Caissa, where its benefactor, Madame Le Bey Tallis, who hobnobbed with the world chess elite, would greet him enthusiastically with “Ah, Monsieur Fooy-ur-steen!” Their stay was extended into 1961 because of the Berlin crisis, caused by Soviet demands for the withdrawal of western troops from West Berlin and sudden construction of the infamous “Berlin Wall.” Indeed, Alice and Art wouldn’t have minded staying even longer in Paris, but Art’s older brother advised him to come back to begin establishing life in the U.S.

“We moved from an apartment on Rue de l’Université in Paris to a four-story walkup in Brooklyn!” Alice said. “But I soon loved Brooklyn too.” Back in New York, Art understandably heard the siren call of a professional chess career. But earning a living was of course the first priority. The couple still remembers a letter Art received congratulating him on winning another brilliancy prize—which amounted to a check for ten dollars and a cheap set that was admittedly on “back-order!” So it was clear chess wouldn’t put caviar on the table, or perhaps even cold cuts. And then Alice met Bobby.

Art brought Alice to a congregation of chess players at Jack Collins’ apartment — also known as the Hawthorne Chess Club, a hub of America’s best, like Donald and Robert Byrne, Lombardy and Fischer. “Bobby came up to say hello, and I introduced him to my wife.” It was clear Art was retelling a foundational family story. Alice took it over. “Bobby looked shocked and ignored me! He kept his eyes on Arty and blurted out, ‘You got married! What did you do that for?’ He was very rude.” The implication was clear, why sacrifice a promising chess career to get married? “I had been friends with Bobby,” Art recalled, “but sometime after the Fischer-Reshevsky match in 1961, I didn’t see him much anymore. And Alice was the best thing that ever happened to me.”

Life-changing accident

Art began working for Sun Chemical, and was soon promoted to more and more responsibility. At the same time, he continued to be a strong force in New York City chess, finishing high in tournament standings, winning the Manhattan Chess Club Championship, playing in another U.S. Championship … and then, on Route 46, on that drive to the Poconos, it all suddenly went dark.

At the insistence of her surgeon-father who was now practicing in Brooklyn, Alice would spend the next six weeks in a torso-covering cast that “was like armor” but allowed her to get around enough to go back and forth to the hospital to visit Art. She credits her complete recovery to her father’s prescription.

Didn’t know what a toothbrush was

The results of Arthur’s head wounds would be more long-lasting, indeed lifelong. “Recovery is still an ongoing process,” Alice said. Art spent six weeks in a semi-coma, sometimes able to respond to simple commands, like instructions to move his head or open his mouth, but not fully conscious and unable to speak. The neurosurgeon in charge of his case told Alice that her husband — the confident business leader and chess champion — would never talk again, and probably never be able to think about anything very complicated. She could only watch as Art lay silent in the hospital bed with a breathing tube in his trachea.

Then one day Alice’s phone rang at home. A nurse told her that Art had pulled out the breathing tube and wanted to talk to her. She rushed to the hospital. What would he say, what would Art be able to do?

When she entered the room, Art and the neurosurgeon, who had also been alerted to the sudden awakening, were hunched over a chessboard. “Honest to God,” Alice said, “he didn’t even know what a toothbrush was, and he only vaguely recognized me, and didn’t know anyone else—but there he was playing a normal game of chess.” “I remembered everything about chess,” Art said, “including my openings.”

Recalling all of this so many years later, Art and Alice sat at their dining room table, with Art’s chess scrapbook open. “You know,” Alice said, “I remember, that a bit later, we heard that the neurosurgeon committed suicide by jumping off the hospital roof.” Perhaps a single heartbeat separated the end of her sad recollection from Art’s devilish response: “Well, I did win that game.” I suppose you develop a dark sense of humor getting through all that’s been put in his path. But the funny young man who won Alice’s heart is still here.

After waking up for that game, Feuerstein spent another two months in the hospital and three years in rehab, relearning the basics of day-to-day life. Through every day of his comeback, Alice was there for him. To support the family, she went back to school and became a highly valued operating-room nurse. Later, she started her own business as a massage therapist, which she continues today.

The man who wasn’t supposed to talk or think well again eventually went on to finish a master of business administration at Baruch and launch a successful, 20-year career as an independent consultant. In 1983 Alice and Arthur had a son, Erik, now creative director of Engage, a political consulting firm.

As for chess, Art continued playing regularly, at the Dumont Chess Mates Club, which over time became the Ridgewood Chess Club, performing well. He remains a perennial top board at the World Team Championship every February. At 65, he was rated in the top ten players in the world in his age group.

And don’t get the idea that just because Arthur is now in his ’70s, he can’t still trade combinations with the best. As recently as the International Chess Academy’s Winter 2010 Open Championship in Fair Lawn, New Jersey, life master Feuerstein defeated both GM Sergey Kudrin and IM Mikhail Zlotnikov to score a perfect 4-0, racking up a performance rating of 2534.

And Alice assures us that he again knows what a toothbrush is.

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (13)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)