Editor’s note: WGM Tatev Abrahamyan is the newest addition to the roster of Chess Life columnists, and this month, we’re pleased to bring her February column out from behind the paywall. Consider becoming a US Chess member for more content like this — access to digital editions of both Chess Life and Chess Life Kids is a member benefit, and you can receive print editions of both magazines for a small add-on fee.

Richard Teichmann might have been exaggerating, but mastering tactics is the quickest way to improve in chess. Once you start spotting tactics in your games with greater frequency and ease, you get a better understanding of how the pieces interact in fruitful ways, and the game becomes both more logical and more fun. The prescription that consistent problem solving is crucial for improvement is a nearly universal training tip, and with very good reason.

As someone who had an “old school” upbringing in chess, I am used to, and still prefer, using books to train, and solving puzzles on a physical board. It’s my experience that it is very helpful for tournament players to solve puzzles on a physical board for visualization purposes. However, I also recognize that there are plenty of resources for tactical work online, many of which can be very helpful.

So how should you study tactics, and what sources should you use? Let’s be a bit more precise, and assume that you have set an hour or two aside for study, and you want to focus on solving. Where to begin?

I think it is very important to be disciplined about your study time. Take care to avoid interruptions and — this is key — do not move the pieces while solving. There are different philosophies when it comes to writing down your analysis as you solve, but I prefer to do it, as it keeps me honest and prevents the “of course I would have seen that” phenomenon when the solution mentions moves I hadn’t considered. If there are important sub-variations, write those down too.

Puzzle Rush

I love Chess.com’s Puzzle Rush (or Puzzle Storm, the Lichess equivalent) but I wouldn’t recommend doing more than two or three sessions during your training. While Puzzle Rush is a good way of reinforcing some basic patterns, doing too many can devolve into bad habits, such as being a bit knee-jerk in move selection and emphasizing known patterns over calculation. That said, I do recommend doing this kind of work as a warm-up for online tournaments, and I will sometimes use my Puzzle Rush score as an indication of my energy levels and alertness.

Online Tactics Trainers

All of the major chess websites offer an endless supply of tactics in traditional tactics trainers. Unlike Puzzle Rush, there is no time limit for solving individual problems, which allows the user to dive into the position. And puzzles can be broken down into themes and categories, allowing the user to train specific areas of the game or specific tactics.

Nevertheless, I see two potential downsides to solving tactics online. First, when you make your move, you get an immediate response from the platform. While this in some ways mimics an actual chess game, it can lead to laziness and our making a move that “looks right” because we know there will be immediate feedback.

Second, sometimes the response is the computer’s top choice, and not the key element of the tactic from a human perspective, i.e., you sacrifice your queen to achieve a checkmate in four moves, but the computer’s engine-driven response is a move that avoids checkmate by throwing away material. This lets you know that your first move is correct, but not necessarily the entire calculation. This is why it is important to slow down and calculate all the branches before trying to solve, and you might consider writing down your analysis here as well.

If you are solving puzzles online and start getting several wrong in a row, remember to avoid getting too emotional. Step away from the computer for a few minutes, or pull out a chess board and set up the position before trying again.

Books

Despite the benefits of online solving, I still prefer books when I want to sharpen my tactics — both for myself, and also for my students. I tend to look for books that are divided into themes, but that also offer sections where the themes are randomized. This is more representative of a real tournament situation; after all, we don’t have anyone whispering what type of tactical themes we should be looking for in our games.

Some of my favorite books that I recommend to students are 1001 Chess Exercises for Beginners (Franco Masetti and Roberto Messa, New in Chess, 2012), 1001 Chess Exercises for Club Players (Frank Erwich, New in Chess, 2019), Manual of Chess Combinations Volumes 1a and 1b (Sergey Ivaschenko, Russian Chess House, 2011, 2014) and A Modern Guide to Checkmating Patterns: Improve Your Ability to Spot Typical Mates (Vladimir Barsky, New in Chess, 2020). The book reviews and author’s notes should give you an indication whether it is appropriate for your level. If the book you have picked up seems too easy, apply a different training method: set a timer and solve as many as possible during that time.

Whether you’re working online or with books, we still need to discuss how to actually solve tactics. Here are some tips:

- Approach the positions methodically: Carefully assess the entire board. Do an overall summary of what is going on in the position, who is ahead in material, and where in general are the pieces aiming. Mentally list as many things as you notice. This is a great tool to use during games when you get stuck in a position. Use your summary as a guide to help you generate candidate moves.

- King safety: are there immediate attacks on the king? Be specific; instead of saying things like “White is attacking,” use more specific language like “the bishop on d3 is aiming at the h7-pawn.”

- Keep track of piece interactions: which pieces are being attacked, and which ones are defending others?

- Look out for loose pieces: is there a piece that is not defended, or not defended sufficiently, that can become a target?

- Ask yourself if your opponent has a threat: This helps indicate the sense of urgency in the position. If your opponent is checkmating you, then you will need to look for forcing moves. If not, then maybe you have time for a quieter move.

- Once you understand the position, look for forcing moves — the moves that make your opponent do something. Examples of forcing moves are checks, captures and threats, such as mating threats or attacks on the queen. If the moves don’t come naturally for you, list them manually, one by one.

Let’s look at a position and try to apply these tips:

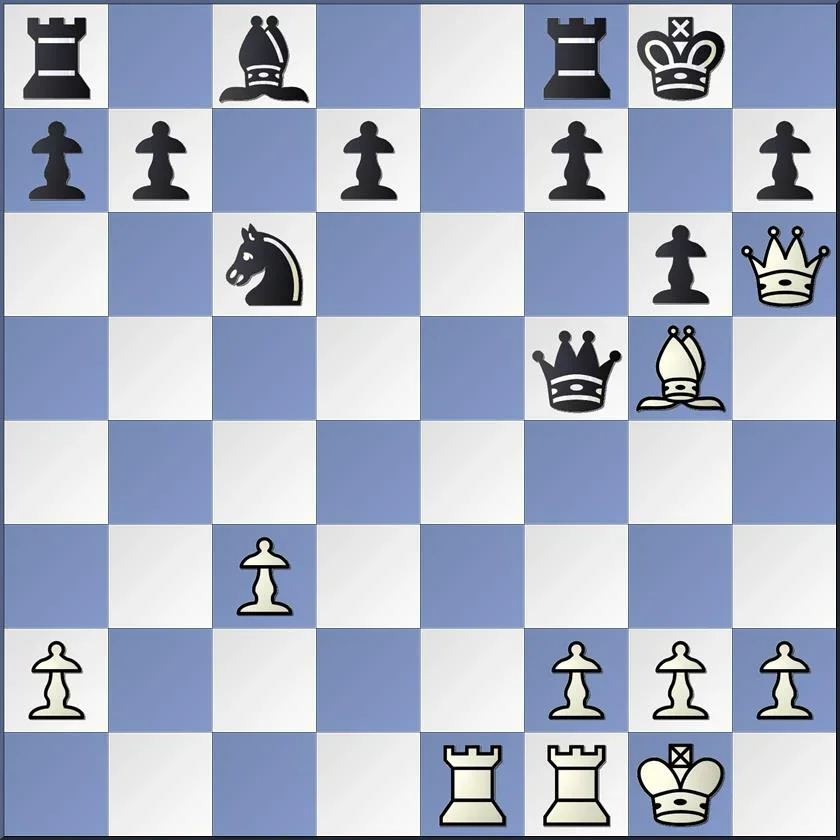

When we give up a piece, the burden is on us to prove that our sacrifice was not in vain. Here, White is down a knight, but is also clearly on the attack. The queen on h6 is limiting the king’s movement, and if the g5-bishop could go to f6, there would be an unstoppable mate with Qh6-g7. One takeaway is that the black queen on f5 is stopping the required bishop move.

There might also be some back-rank issues in the Black camp, as we see the e1-rook on the open file along with disconnected black rooks due to the c8-bishop.

Black’s only defensive pieces are the f8-rook and the queen. Since the bishop cannot go to f6, and we can’t distract the queen from defending the f6-square, we should consider another configuration using the back-rank weakness.

That’s just what then-IM Judit Polgar did in the position at the bottom of the previous column. Playing against WIM Pavlina Chilingirova at the 1988 Women’s Olympiad, Polgar uncorked 17. Qxf8+, and Black resigned. With her move, Polgar eliminated the defender of the back-rank. The key variation is 17. ... Kxf8 18. Bh6+ Kg8 19. Re8 mate.

Finding these sacrifices and ideas becomes more natural with practice. Part of that practice should be keeping track of the kind of puzzles you fail to solve, and trying to find patterns in your misses. That gives you a sense of what themes you might need to work on.

Also remember that when solving, it is very unlikely that your mistake will happen on the 10th move in the variation. Most of our mistakes happen early in our calculation, as we overlook or misevaluate an important detail. Spend time looking at all the possibilities early on.

With practice and hard work, we can apply this knowledge to our games. Of course it’s a bit different over-the-board: while solving puzzles, we know that there is a solution and we can keep trying until we find it, but we are on our own during games, with no one nudging us to look for that beautiful queen sacrifice. So we need to be more diligent in our calculations, and we must put serious effort into finding our opponent’s resources.

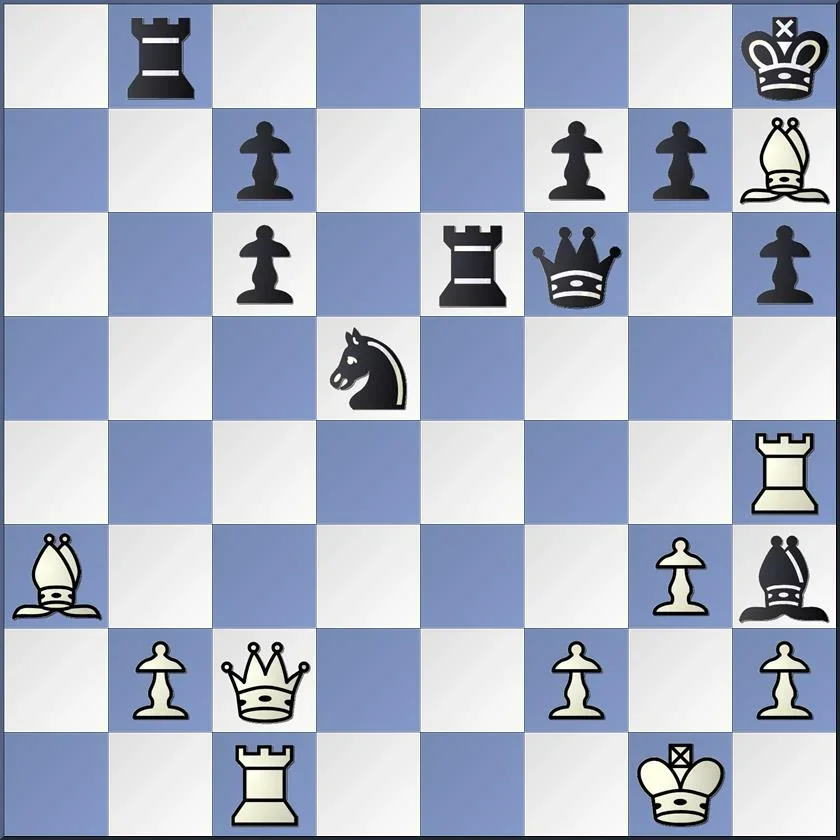

Here’s an example of how everything can come together. I returned to St. Louis this past December to play in the 2022 SPICE Cup. In the following game, I set a trap for my opponent because I thought he would be tempted to play into this position. Since I was very familiar with the type of tactic Polgar played in her game, it worked out beautifully for me.

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (8)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)