In 2013,

Dr. Alan M. Kirshner wrote about International Games Day @ your library. His volunteers played blitz chess, separately taught beginners and more advanced players, gave a simultaneous exhibition, and projected chess movies. Chess attracted 120 Fremont, CA library patrons.

If your local library will attract fewer chess-interested patrons, you can be a lone chess volunteer. This article provides four ideas for you to promote chess all by yourself at

International Games Day @ your library.

1) Start early. September 11 was the deadline for librarians to request free games by registering for the November 21, 2015 International Games Day. The companies

Good Games,

Konami,

Looney Labs,

Steve Jackson Games,

USAopoly,

Yummy Yummy Tummy, and

Asmodee donated games to participating libraries. Your mentioning this chance to build a collection of games will endear you to your local librarian. Then you can ask your librarian for chess to be a part of International Games Day.

2) Get supplies. Since I was the only chess volunteer at the Denton (TX) Public Library, North Branch, for International Games Day, I planned just two activities, playing chess and solving checkmate puzzles. For playing chess, Public Services Librarians Dana M. Tucker and Kerol S. Harrod supplied chess sets and boards. Since the North Branch Library hosts a chess club every Monday evening, the sets and boards were already stored at the library.

For solving checkmate puzzles, I provided four levels of puzzle sheets. (Dana and Kerol offered to photocopy for me, but I had photocopies available in my own chess teaching supplies.) The Novice puzzle sheet had Boden’s checkmates (downloaded from

KidChess.com). Those puzzles had only a few chessmen on each diagram. Intermediate puzzles, from KidChess.com, were also checkmate-in-one move, but with more chessmen on each diagram. The Novice and Intermediate puzzle sheets had four diagrams to a sheet. For the Advanced level sheet, I chose leftover assessments from the

UT Dallas Chess Camp. That six-puzzle sheet had two checkmate-in-one move and four checkmate-in-two move diagrams. For the Expert level, I created six puzzles from famous games (such as the Immortal Game) which were checkmates in two or three moves.

3) Have a procedure.

3) Have a procedure. When patrons played each other chess, they called me over to their games to answer questions: “Can each pawn move two squares on its first move, or only the first pawn that moves in a game?” “Can I promote to a queen if I already have a queen on the board?” “How do I castle?” To be available to answer questions, I avoided playing chess myself. For example, when a complete beginner came into the room, I asked a senior citizen to teach that beginner instead of my teaching him. That senior citizen had been telling me about how many years he had played, so I thought that he probably knew the rules. The older man relished the chance to teach. The senior citizen even gave the beginner, a middle-aged adult man, his business card and said that he would be happy to play chess with him again.

After library patrons played chess with each other, some were interested in the chess puzzle sheets. They answered by drawing arrows on the diagrams rather than using notation. Patrons put their names and phone numbers on one of their puzzle sheets to be entered in the drawing for a prize.

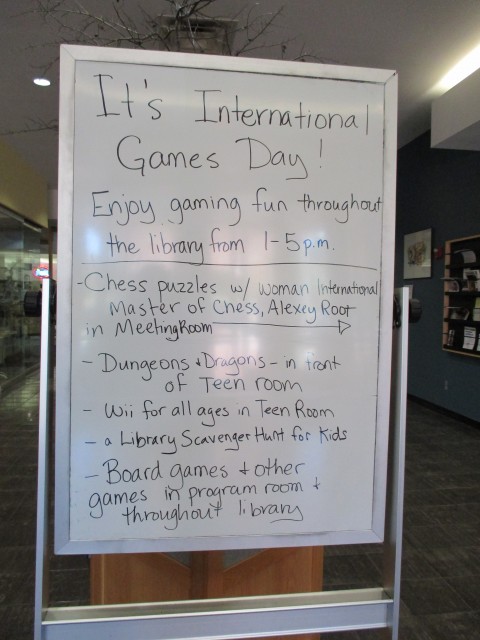

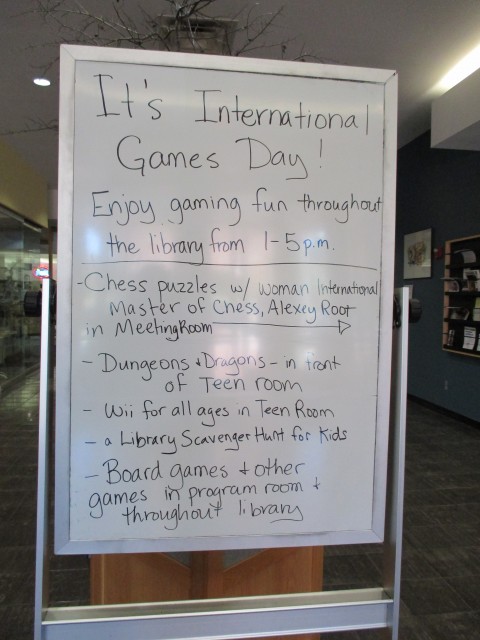

The prizes were four chess T-shirts and three chess medals, leftovers from the UT Dallas Chess Camp. One entry (puzzle sheet) per person was allowed, even if the person completed all four sheets. Throughout the afternoon, I tracked on the dry erase board (using first names and last initials) results on the four levels of puzzles (Novice, Intermediate, Advanced, and Expert). One could look at the board and say, for example, “Hey, Kerol H. got 4 of 4 right on the Novice puzzles!” Or, “Dana T. got 3 out of 4 correct on the Intermediate puzzles!” Getting puzzles right did not affect one’s chances in the prize drawing. But some people like to see their names on the dry erase board (like a "top score" tracker on a video game). After patrons turned in their puzzle sheets, I pointed out which answers were right and wrong. Most patrons wanted to try again on the puzzles that they had missed.

Toward the end of International Games Day, which ran from 1:00 to 5:00 p.m. at my library, I handed out the prizes. Had I not been able to find the winners still at the library, Dana and Kerol would have used the phone numbers on the puzzle sheets to contact the patrons to claim their prizes.

4) Share chess opportunities and books. Through volunteering, I promoted local chess resources. When patrons asked, “Where can I play chess again?” I mentioned the Monday night Denton Public Library chess club, the

Barnes & Noble club in Lewisville (about 16 miles away), and the

Dallas Chess Club (a one-hour drive). After parents saw the prizes from the UT Dallas Chess Camp, they asked me for information about chess camps. In addition to UT Dallas,

Coppell Gifted Association,

Greenhill School (Addison),

McKinney Chess, and

SCA Chess (Fort Worth) offer chess camps within a one-hour drive from Denton, TX.

As appropriate in a library setting, I talked about chess books and films. One father mentioned that his ten-year-old homeschooled son had learned chess from a book with a “Gary” in it. I asked, “Garry Kasparov?” The father said no, the book was

Gary’s Adventures in Chess Country. I mentioned that my sixth book,

Thinking With Chess: Teaching Children Ages 5-14, was from the same publisher (Mongoose Press). The older man had seen the film

Searching for Bobby Fischer and wanted to know what Josh Waitzkin did now. So I gave him the name of Waitzkin’s book

The Art of Learning. A mother of a fourth grader later mentioned the same film. I told her that, in the film, actor Ben Kingsley portrayed chess teacher Bruce Pandolfini. I recommended Pandolfini books such as

Beginning Chess for her son. I told her about

Brooklyn Castle, a documentary film about middle school children and chess, available for check out at the Denton Public Library.

Around 4:30 p.m., when no one had visited the chess room during the previous five minutes, I began packing up the chess sets and boards. Then a young man with a red beard walked in. I asked him if he wanted to try chess puzzles or if he wanted to play me a game of chess. He said, “Don’t you remember me? I was in your Strickland Middle School chess class.” Once he said his name (Andrew G.), I remembered him. Andrew didn’t have a beard eight years ago! Andrew and I played three games. I was pleased that Andrew remembered much of what I had taught him, such as developing his chessmen and castling. He said that he still plays chess, usually via computer. I was glad that my volunteering at Strickland led Andrew to make chess a part of his life. Perhaps I will encounter the library patrons I met on November 21, 2015 years from now, still playing chess.

Dr. Alexey Root teaches online courses on using chess for educational purposes. More information about her, and about the courses, is at http://www.utdallas.edu/is/faculty-staff/alexey-root/ In 2013, Dr. Alan M. Kirshner wrote about International Games Day @ your library. His volunteers played blitz chess, separately taught beginners and more advanced players, gave a simultaneous exhibition, and projected chess movies. Chess attracted 120 Fremont, CA library patrons.

If your local library will attract fewer chess-interested patrons, you can be a lone chess volunteer. This article provides four ideas for you to promote chess all by yourself at International Games Day @ your library.

1) Start early. September 11 was the deadline for librarians to request free games by registering for the November 21, 2015 International Games Day. The companies Good Games, Konami, Looney Labs, Steve Jackson Games, USAopoly, Yummy Yummy Tummy, and Asmodee donated games to participating libraries. Your mentioning this chance to build a collection of games will endear you to your local librarian. Then you can ask your librarian for chess to be a part of International Games Day.

2) Get supplies. Since I was the only chess volunteer at the Denton (TX) Public Library, North Branch, for International Games Day, I planned just two activities, playing chess and solving checkmate puzzles. For playing chess, Public Services Librarians Dana M. Tucker and Kerol S. Harrod supplied chess sets and boards. Since the North Branch Library hosts a chess club every Monday evening, the sets and boards were already stored at the library.

For solving checkmate puzzles, I provided four levels of puzzle sheets. (Dana and Kerol offered to photocopy for me, but I had photocopies available in my own chess teaching supplies.) The Novice puzzle sheet had Boden’s checkmates (downloaded from KidChess.com). Those puzzles had only a few chessmen on each diagram. Intermediate puzzles, from KidChess.com, were also checkmate-in-one move, but with more chessmen on each diagram. The Novice and Intermediate puzzle sheets had four diagrams to a sheet. For the Advanced level sheet, I chose leftover assessments from the UT Dallas Chess Camp. That six-puzzle sheet had two checkmate-in-one move and four checkmate-in-two move diagrams. For the Expert level, I created six puzzles from famous games (such as the Immortal Game) which were checkmates in two or three moves.

In 2013, Dr. Alan M. Kirshner wrote about International Games Day @ your library. His volunteers played blitz chess, separately taught beginners and more advanced players, gave a simultaneous exhibition, and projected chess movies. Chess attracted 120 Fremont, CA library patrons.

If your local library will attract fewer chess-interested patrons, you can be a lone chess volunteer. This article provides four ideas for you to promote chess all by yourself at International Games Day @ your library.

1) Start early. September 11 was the deadline for librarians to request free games by registering for the November 21, 2015 International Games Day. The companies Good Games, Konami, Looney Labs, Steve Jackson Games, USAopoly, Yummy Yummy Tummy, and Asmodee donated games to participating libraries. Your mentioning this chance to build a collection of games will endear you to your local librarian. Then you can ask your librarian for chess to be a part of International Games Day.

2) Get supplies. Since I was the only chess volunteer at the Denton (TX) Public Library, North Branch, for International Games Day, I planned just two activities, playing chess and solving checkmate puzzles. For playing chess, Public Services Librarians Dana M. Tucker and Kerol S. Harrod supplied chess sets and boards. Since the North Branch Library hosts a chess club every Monday evening, the sets and boards were already stored at the library.

For solving checkmate puzzles, I provided four levels of puzzle sheets. (Dana and Kerol offered to photocopy for me, but I had photocopies available in my own chess teaching supplies.) The Novice puzzle sheet had Boden’s checkmates (downloaded from KidChess.com). Those puzzles had only a few chessmen on each diagram. Intermediate puzzles, from KidChess.com, were also checkmate-in-one move, but with more chessmen on each diagram. The Novice and Intermediate puzzle sheets had four diagrams to a sheet. For the Advanced level sheet, I chose leftover assessments from the UT Dallas Chess Camp. That six-puzzle sheet had two checkmate-in-one move and four checkmate-in-two move diagrams. For the Expert level, I created six puzzles from famous games (such as the Immortal Game) which were checkmates in two or three moves.

3) Have a procedure. When patrons played each other chess, they called me over to their games to answer questions: “Can each pawn move two squares on its first move, or only the first pawn that moves in a game?” “Can I promote to a queen if I already have a queen on the board?” “How do I castle?” To be available to answer questions, I avoided playing chess myself. For example, when a complete beginner came into the room, I asked a senior citizen to teach that beginner instead of my teaching him. That senior citizen had been telling me about how many years he had played, so I thought that he probably knew the rules. The older man relished the chance to teach. The senior citizen even gave the beginner, a middle-aged adult man, his business card and said that he would be happy to play chess with him again.

After library patrons played chess with each other, some were interested in the chess puzzle sheets. They answered by drawing arrows on the diagrams rather than using notation. Patrons put their names and phone numbers on one of their puzzle sheets to be entered in the drawing for a prize.

The prizes were four chess T-shirts and three chess medals, leftovers from the UT Dallas Chess Camp. One entry (puzzle sheet) per person was allowed, even if the person completed all four sheets. Throughout the afternoon, I tracked on the dry erase board (using first names and last initials) results on the four levels of puzzles (Novice, Intermediate, Advanced, and Expert). One could look at the board and say, for example, “Hey, Kerol H. got 4 of 4 right on the Novice puzzles!” Or, “Dana T. got 3 out of 4 correct on the Intermediate puzzles!” Getting puzzles right did not affect one’s chances in the prize drawing. But some people like to see their names on the dry erase board (like a "top score" tracker on a video game). After patrons turned in their puzzle sheets, I pointed out which answers were right and wrong. Most patrons wanted to try again on the puzzles that they had missed.

Toward the end of International Games Day, which ran from 1:00 to 5:00 p.m. at my library, I handed out the prizes. Had I not been able to find the winners still at the library, Dana and Kerol would have used the phone numbers on the puzzle sheets to contact the patrons to claim their prizes.

4) Share chess opportunities and books. Through volunteering, I promoted local chess resources. When patrons asked, “Where can I play chess again?” I mentioned the Monday night Denton Public Library chess club, the Barnes & Noble club in Lewisville (about 16 miles away), and the Dallas Chess Club (a one-hour drive). After parents saw the prizes from the UT Dallas Chess Camp, they asked me for information about chess camps. In addition to UT Dallas, Coppell Gifted Association, Greenhill School (Addison), McKinney Chess, and SCA Chess (Fort Worth) offer chess camps within a one-hour drive from Denton, TX.

3) Have a procedure. When patrons played each other chess, they called me over to their games to answer questions: “Can each pawn move two squares on its first move, or only the first pawn that moves in a game?” “Can I promote to a queen if I already have a queen on the board?” “How do I castle?” To be available to answer questions, I avoided playing chess myself. For example, when a complete beginner came into the room, I asked a senior citizen to teach that beginner instead of my teaching him. That senior citizen had been telling me about how many years he had played, so I thought that he probably knew the rules. The older man relished the chance to teach. The senior citizen even gave the beginner, a middle-aged adult man, his business card and said that he would be happy to play chess with him again.

After library patrons played chess with each other, some were interested in the chess puzzle sheets. They answered by drawing arrows on the diagrams rather than using notation. Patrons put their names and phone numbers on one of their puzzle sheets to be entered in the drawing for a prize.

The prizes were four chess T-shirts and three chess medals, leftovers from the UT Dallas Chess Camp. One entry (puzzle sheet) per person was allowed, even if the person completed all four sheets. Throughout the afternoon, I tracked on the dry erase board (using first names and last initials) results on the four levels of puzzles (Novice, Intermediate, Advanced, and Expert). One could look at the board and say, for example, “Hey, Kerol H. got 4 of 4 right on the Novice puzzles!” Or, “Dana T. got 3 out of 4 correct on the Intermediate puzzles!” Getting puzzles right did not affect one’s chances in the prize drawing. But some people like to see their names on the dry erase board (like a "top score" tracker on a video game). After patrons turned in their puzzle sheets, I pointed out which answers were right and wrong. Most patrons wanted to try again on the puzzles that they had missed.

Toward the end of International Games Day, which ran from 1:00 to 5:00 p.m. at my library, I handed out the prizes. Had I not been able to find the winners still at the library, Dana and Kerol would have used the phone numbers on the puzzle sheets to contact the patrons to claim their prizes.

4) Share chess opportunities and books. Through volunteering, I promoted local chess resources. When patrons asked, “Where can I play chess again?” I mentioned the Monday night Denton Public Library chess club, the Barnes & Noble club in Lewisville (about 16 miles away), and the Dallas Chess Club (a one-hour drive). After parents saw the prizes from the UT Dallas Chess Camp, they asked me for information about chess camps. In addition to UT Dallas, Coppell Gifted Association, Greenhill School (Addison), McKinney Chess, and SCA Chess (Fort Worth) offer chess camps within a one-hour drive from Denton, TX.

As appropriate in a library setting, I talked about chess books and films. One father mentioned that his ten-year-old homeschooled son had learned chess from a book with a “Gary” in it. I asked, “Garry Kasparov?” The father said no, the book was Gary’s Adventures in Chess Country. I mentioned that my sixth book, Thinking With Chess: Teaching Children Ages 5-14, was from the same publisher (Mongoose Press). The older man had seen the film Searching for Bobby Fischer and wanted to know what Josh Waitzkin did now. So I gave him the name of Waitzkin’s book The Art of Learning. A mother of a fourth grader later mentioned the same film. I told her that, in the film, actor Ben Kingsley portrayed chess teacher Bruce Pandolfini. I recommended Pandolfini books such as Beginning Chess for her son. I told her about Brooklyn Castle, a documentary film about middle school children and chess, available for check out at the Denton Public Library.

Around 4:30 p.m., when no one had visited the chess room during the previous five minutes, I began packing up the chess sets and boards. Then a young man with a red beard walked in. I asked him if he wanted to try chess puzzles or if he wanted to play me a game of chess. He said, “Don’t you remember me? I was in your Strickland Middle School chess class.” Once he said his name (Andrew G.), I remembered him. Andrew didn’t have a beard eight years ago! Andrew and I played three games. I was pleased that Andrew remembered much of what I had taught him, such as developing his chessmen and castling. He said that he still plays chess, usually via computer. I was glad that my volunteering at Strickland led Andrew to make chess a part of his life. Perhaps I will encounter the library patrons I met on November 21, 2015 years from now, still playing chess.

Dr. Alexey Root teaches online courses on using chess for educational purposes. More information about her, and about the courses, is at http://www.utdallas.edu/is/faculty-staff/alexey-root/

As appropriate in a library setting, I talked about chess books and films. One father mentioned that his ten-year-old homeschooled son had learned chess from a book with a “Gary” in it. I asked, “Garry Kasparov?” The father said no, the book was Gary’s Adventures in Chess Country. I mentioned that my sixth book, Thinking With Chess: Teaching Children Ages 5-14, was from the same publisher (Mongoose Press). The older man had seen the film Searching for Bobby Fischer and wanted to know what Josh Waitzkin did now. So I gave him the name of Waitzkin’s book The Art of Learning. A mother of a fourth grader later mentioned the same film. I told her that, in the film, actor Ben Kingsley portrayed chess teacher Bruce Pandolfini. I recommended Pandolfini books such as Beginning Chess for her son. I told her about Brooklyn Castle, a documentary film about middle school children and chess, available for check out at the Denton Public Library.

Around 4:30 p.m., when no one had visited the chess room during the previous five minutes, I began packing up the chess sets and boards. Then a young man with a red beard walked in. I asked him if he wanted to try chess puzzles or if he wanted to play me a game of chess. He said, “Don’t you remember me? I was in your Strickland Middle School chess class.” Once he said his name (Andrew G.), I remembered him. Andrew didn’t have a beard eight years ago! Andrew and I played three games. I was pleased that Andrew remembered much of what I had taught him, such as developing his chessmen and castling. He said that he still plays chess, usually via computer. I was glad that my volunteering at Strickland led Andrew to make chess a part of his life. Perhaps I will encounter the library patrons I met on November 21, 2015 years from now, still playing chess.

Dr. Alexey Root teaches online courses on using chess for educational purposes. More information about her, and about the courses, is at http://www.utdallas.edu/is/faculty-staff/alexey-root/