Editor’s note:

Our January issue featured this piece by Chess Life editor John Hartmann, in which he summarizes the events and issues surrounding what he calls “the Niemann affair,” and in which he tries to think through the longer-term ramifications of this critical event in chess history.

One of the enduring values of print journalism is that it allows authors and readers time to think and digest. Those heady September days were thick with accusations and innuendo, and in real-time, it was very hard to do anything but surf the social media waves.

With distance comes the chance for context, synthesis, and critical thinking. This is what we tried to work towards in this article. It is not simply a recitation of the facts — although it is also that — but a study of “l’affaire Niemann” in all of its depth and import.

You can find more articles like this every month in Chess Life, digital access to which is just one of the benefits of US Chess membership. A print subscription is available to all members for a small add-on fee. You may view the print version of this article here.

If you are not a member, consider joining to read the magazine that the Chess Journalists of America named “best magazine” in 2022.

What has come to be known as the “butterfly effect” is a complicated mathematical definition within modern chaos theory that can be grasped with a simple metaphor.

Imagine a butterfly, flittering around the milkweed plants in your garden. The tiny atmospheric disturbance caused by the monarch’s beating wings might — not will, but might — be the first element in a causal chain that leads to, or prevents, a major weather event like a tornado. This is the butterfly effect: the idea that a small, local action might unpredictably snowball beyond its immediate conditions and change the world.

GM Richard Rapport is just such a butterfly.

Were one to “let the chess speak for itself,” the story of the 2022 editions of the Saint Louis Rapid and Blitz, the Sinquefield Cup, and the Champions Showdown 9LX tournaments at the Saint Louis Chess Club would be the play of GM Alireza Firouzja. After a disappointing performance in the 2022 Candidates Tournament, Firouzja was absolutely dominant, winning the Rapid and Blitz outright, and sharing first in the Sinquefield Cup and Champions Showdown 9LX, taking the former in a playoff.

This was the breakout performance that everyone had been waiting for, including the young French-Iranian himself, who revealed in an interview with GM Cristian Chirila that had he had vowed to win his first tournament on Missouri soil. Firouzja played creative and combative chess on the way to becoming the 2022 Grand Chess Tour champion, and it signaled his place both as a potential title challenger in the future, and as one of today’s elite now.

But no one talks about Firouzja’s victories. After leaving St. Louis, and outside of his weekly Titled Tuesday appearances, he has largely retreated from the contemporary chess landscape. Instead, with a few flaps of Rapport’s wings, another name has been inserted into its beating heart.

GM Hans Niemann wasn’t even supposed to be there. The peripatetic American was playing in the Turkish league when he got the call. COVID-19 related travel restrictions forced Rapport to withdraw from the Rapid and Blitz and the Sinquefield Cup. Could Hans make it back to St. Louis and fill one of the spots?

The Rapid and Blitz was too soon — GM Jeffery Xiong filled in admirably there — but soon enough Niemann was back in St. Louis, taking his place among the simultaneous exhibitors at the Sinquefield Cup opening ceremony.

I was there, that Thursday night in Forest Park. If you look at the various photos from the event, you’ll see me in my Star Wars themed RSVLTS shirt, looking haggard while playing blitz, or holding up a copy of Chess Life for the cameras. And looking back at what I saw, already there were hints that something was not quite right.

Carlsen was a little chippy as he was interviewed during the simul by GM Cristian Chirila and WGM Anastasiya Karlovich, taking what very much felt like digs at Niemann as the two made their respective moves. As soon as the games were ended and the autographs signed, Team Carlsen disappeared, making for a very awkward moment at the event opening when Carlsen’s name was called and he was nowhere to be found.

By itself, this might not have meant anything at all. But in the weeks since “l’affaire Niemann” began, we’ve come to know quite a lot about the behind-the-scenes machinations of top-level chess. One of the things we learned from Chirila and GM Fabiano Caruana’s must-listen “C-Squared Podcast” is that Carlsen was protesting Niemann’s playing in the Sinquefield Cup as soon as he learned of it.

What could have caused this rift? After all, Niemann was a regular participant in Play Magnus tour events, and we now know that Carlsen and Niemann played friendly games on a Miami beach on August 12. So what happened in the intervening days between the 12th and 25th, when Niemann’s participation was announced?

Perhaps it was Niemann’s petulant proclamation “the chess speaks for itself,” spat at a Chess24 reporter after defeating Carlsen in the first game of their FTX (yes, that FTX) Crypto Cup match — a match that Carlsen went on to win by a score of 3-1.

But perhaps there was more to it. Niemann, it seems, has been the subject of long-standing rumors regarding online cheating, a subject that had not received much public attention, but was of great concern to the world’s leading players. It’s not clear how Carlsen could have come to know of Niemann’s juvenile bans from Chess.com events — he had been playing in Chess.com prize tournaments regularly, and Chess24 had no apparent problems with Niemann’s participation — but, for whatever reason, he was perturbed.

The first days of the Sinquefield Cup saw nothing out of the ordinary. Carlsen stylishly defeated GM Ian Nepomniachtchi in round one. Nepo took out his frustrations on Firouzja in round two, while Niemann won a nice game against GM Shakhriyar Mamedyarov.

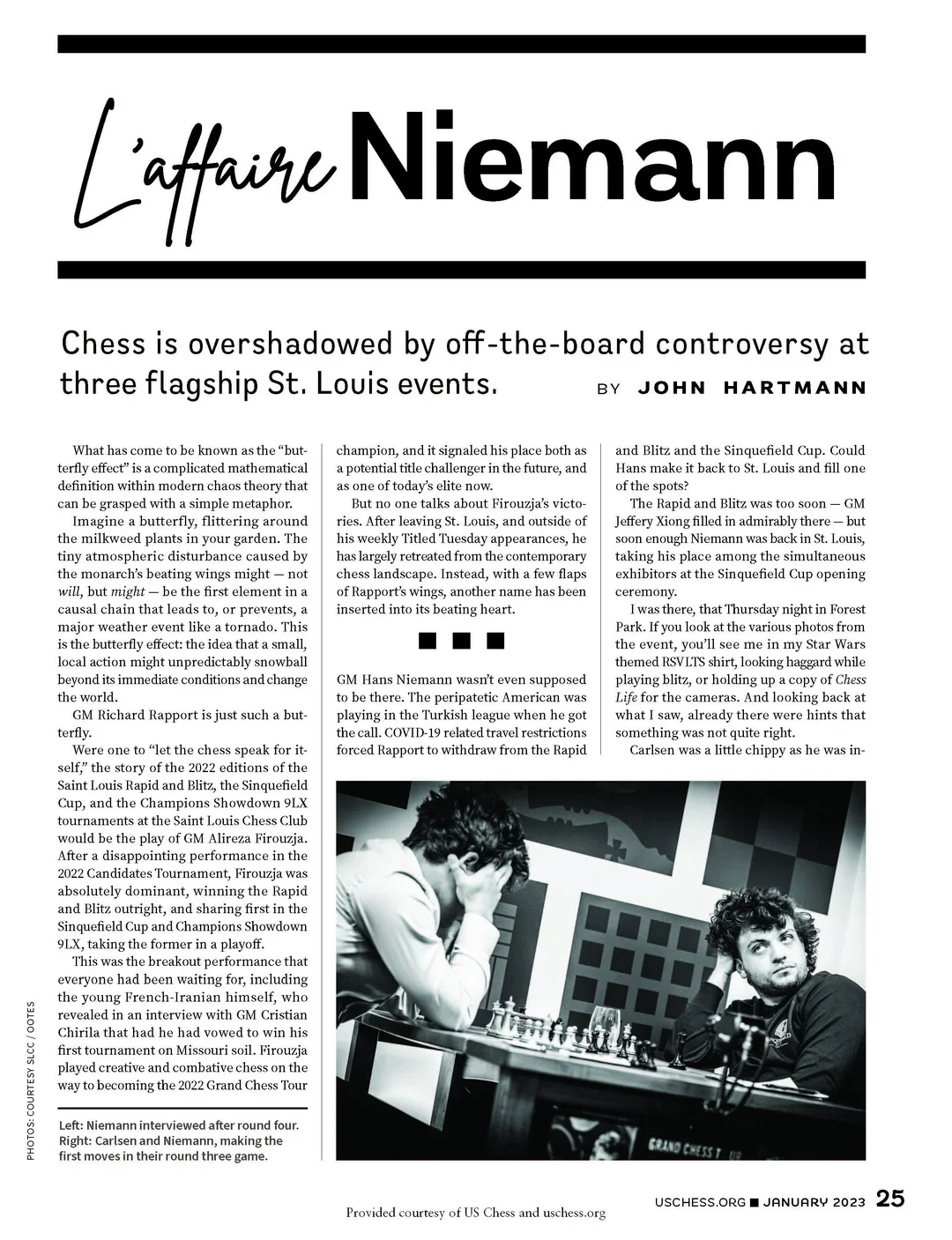

And then came round three, and this pairing — one that overturned the chess world as we know it.

Niemann’s post-game interview raised more than a few eyebrows. Switching in and out of a strange accent, he said that he had “by some miracle” checked the opening position that day — an admission that got a lot of air time in the ensuing social media melee — and, with his usual bravado, claimed that Magnus must be shattered to “lose against such an idiot like me. It must be embarrassing for the World Champion to lose to me. I feel bad for him.”

For his part, Carlsen had seen enough. The rumors started to circulate on social media as round four began with a 15-minute broadcast delay; soon, we learned that Carlsen failed to show up for his game with Mamedyarov, choosing instead to withdraw from the event. His only comment was a cryptic tweet announcing his departure, giving a curious link to a Jose Mourinho “If I speak, I am in big trouble” video as a chaser. For those not in the know: Mourinho was referring to what he saw as colossal refereeing errors during a 2014 Chelsea football game.

Chess social media exploded: while Carlsen coyly avoided fingering Niemann as a cheat, everyone very quickly read between the lines and began to speculate. Prominent chess streamers like GMs Hikaru Nakamura and Eric Hansen immediately talked about and around rumors of Niemann’s past online cheating, his bans from Chess.com, and the various ways that he might have cheated over-the-board against Carlsen. Multiple theories, some very strange, began to emerge. Some focused on leaked prep from Carlsen’s camp. Others were more... esoteric.

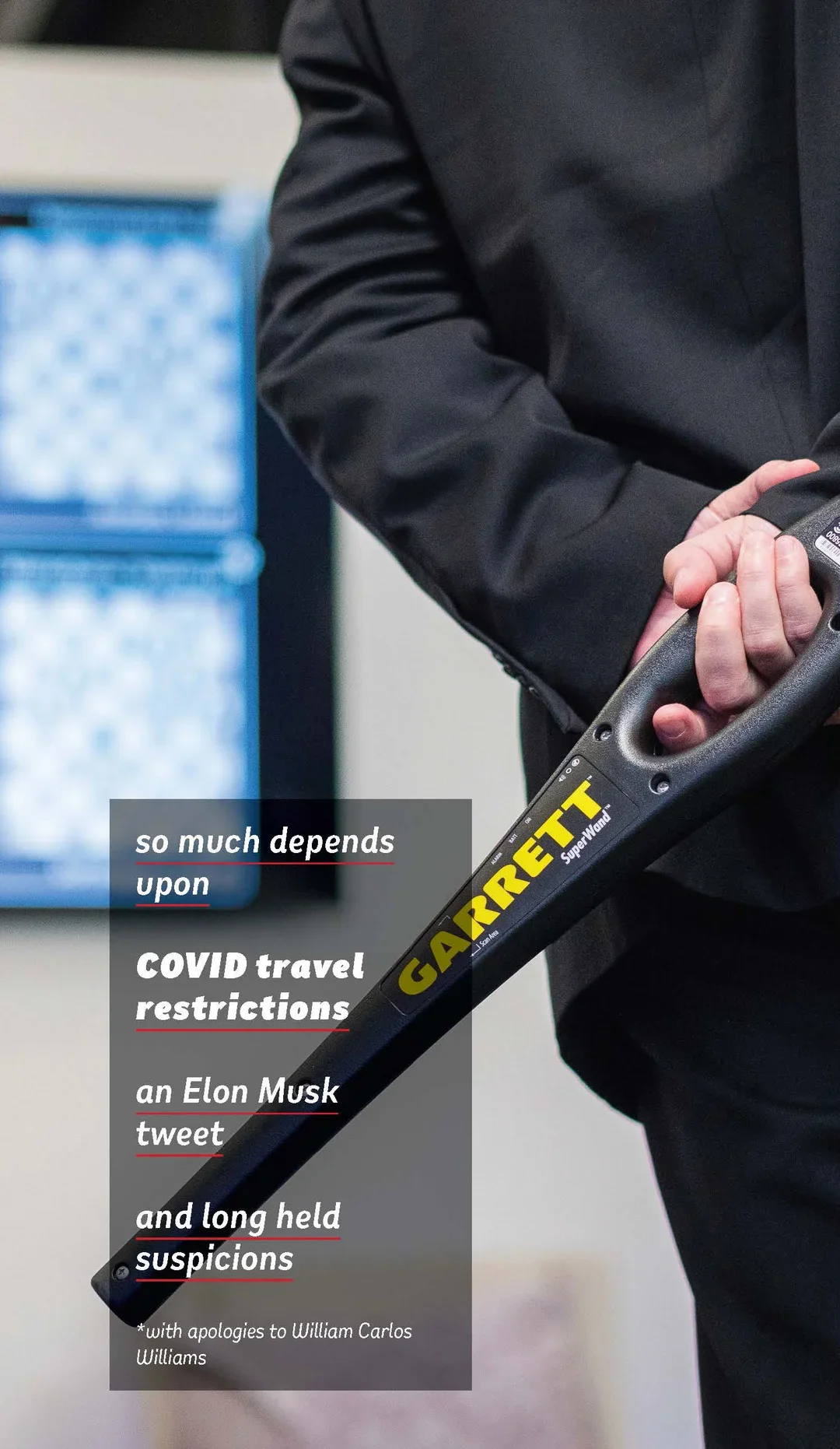

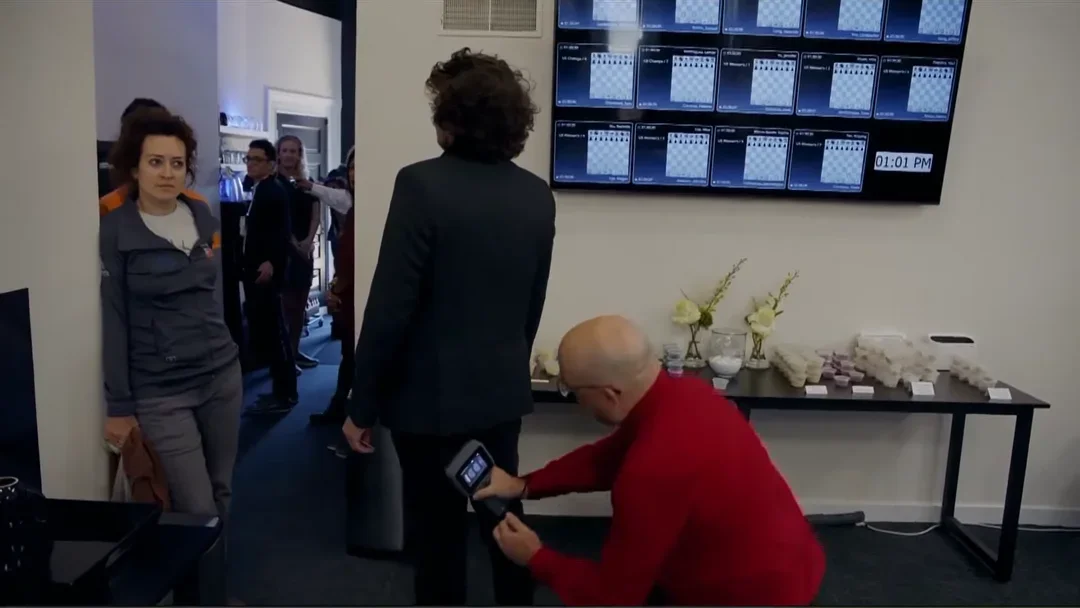

Now, I was in the room for the beginning of the first round, and I watched as IA Chris Bird explained the security measures to the players. I can’t prove that Niemann didn’t cheat — it’s nearly impossible to prove a negative — but it’s very hard to see how he could have pulled it off.

Spectators weren’t allowed in the hall, and journalists / guests of the event had to leave after the first 10 minutes. Players were wanded at the door, and all electronics had to be surrendered upon entry. The players could not leave the playing hall without a chaperone, and with only one bathroom, there was no place to hide a cell phone a la Igor Rausis.

Carlsen was in that same room for those same announcements, and presumably he had been given similar information during the players’ meeting before the tournament began. He had to have known how tricky it would be to pull off that kind of scheme. So why did he withdraw from the event, an action that is almost unthinkable at elite levels, and one that would be sure to draw the ire of the Saint Louis leadership?

I don’t think outsiders were — or are — aware of just how troubled top players are by the prospect of cheating. Equipped with Stockfish, today’s cell phones are more than strong enough to defeat any human alive. Consulting the engine even once or twice a game could be enough for a savvy player to turn a loss into a win. And Niemann’s history with engine use in online games was not unknown to his fellow grandmasters.

Interviews with other Sinquefield participants confirmed this. With a wink and a nod, Nepomniachtchi called Niemann’s victory “most impressive” in an interview after round four; soon, a year-old video of Nepo wondering how much Niemann was using an engine to harvest rating points emerged. GM Levon Aronian admitted that his colleagues could be “paranoid” about young players making leaps in strength. Caruana suggested that people were probably right to guess what made Carlsen withdraw.

I think — and here I’m just speculating — that Carlsen saw himself as taking a stand against cheating in chess, tearing the band-aid off a wound that very few outside of top-level chess knew about. Whether he could prove that Niemann cheated in their game was, in some ways, irrelevant. The well was already poisoned, and Niemann’s in-game behavior was just the tipping point.

Meanwhile, the other competitors soldiered on. Niemann drew a fascinating game against Firouzja; afterwards, he struggled through a post-game interview where, in contrast to previous days, the Lichess engine was turned off. This was more fuel for the fire: Eric Hansen called Niemann’s analysis “incoherent” without access to the engine, and soon suggested that a carefully secreted, vibrating adult toy would be one way to defeat the security checks and receive in-game assistance.

This was chum in the water, and what was a big story in the chess world suddenly took on a life beyond it. After the world’s second richest man (at time of writing) and walking embodiment of the Dunning-Kreuger effect Elon Musk tweeted [update: and since deleted] about Hansen’s “theory,” the mass media machine swarmed, and chess players everywhere had to answer uncomfortable questions from their friends.

Niemann’s response to the controversy was to give one of the most remarkable interviews in chess history on September 6. For nearly 20 minutes after his round five draw with GM Leinier Dominguez Perez, Niemann addressed every aspect of the controversy in detail. He admitted to cheating in online games when he was 12 and 16, and to being banned (and then restored) for those offenses. He unequivocally denied cheating against Carlsen, and offered to play naked, if need be, to prove his innocence.

Perhaps most troubling was his assertion that Chess.com re-banned him because of the charges leveled by their new business partner, Magnus Carlsen. (Recall that Chess.com announced plans to purchase the Play Magnus Group on August 24.) Why, he asked, would “someone very high up at Chess.com” — quite possibly IM Danny Rensch himself, who was on-site in St. Louis for the first days of the event — personally tell him three days earlier that he’d be welcome in the Chess.com Global Chess Championship, only to have his account “privately rescinded” after defeating Carlsen?

There may have been four rounds of chess to go, but for all intents and purposes, the tournament was at this point over. All of the oxygen in the room was sucked up by the insatiable churn of social media, and the “chess itself” became little more than excuse to gossip and retweet.

(For the record: Firouzja shared first with Mamedyarov, defeating him in a playoff to claim the actual Sinquefield Cup. See key annotated games by IM John Watson in our February issue.)

The off-the-board moves slowed, but they kept coming. Niemann challenged Nakamura and Hansen to watch his interview and respond. Play Magnus published and quickly deleted a story about the “biggest cheating scandals” in chess history. Chess.com defended themselves in a September 8th tweet, stating that Niemann was informed as to the reasons for his removal from their events, and promising to “protect the integrity of the game that we all love.”

On September 10, Sinquefield arbiter Bird released a statement, confirming that there was “no indication that any player has been playing unfairly in the 2022 Sinquefield Cup.” That same day, four Robert Palmer video-esque “Niemann fans” held a vigil outside the playing hall in honor of their hirsute hero.

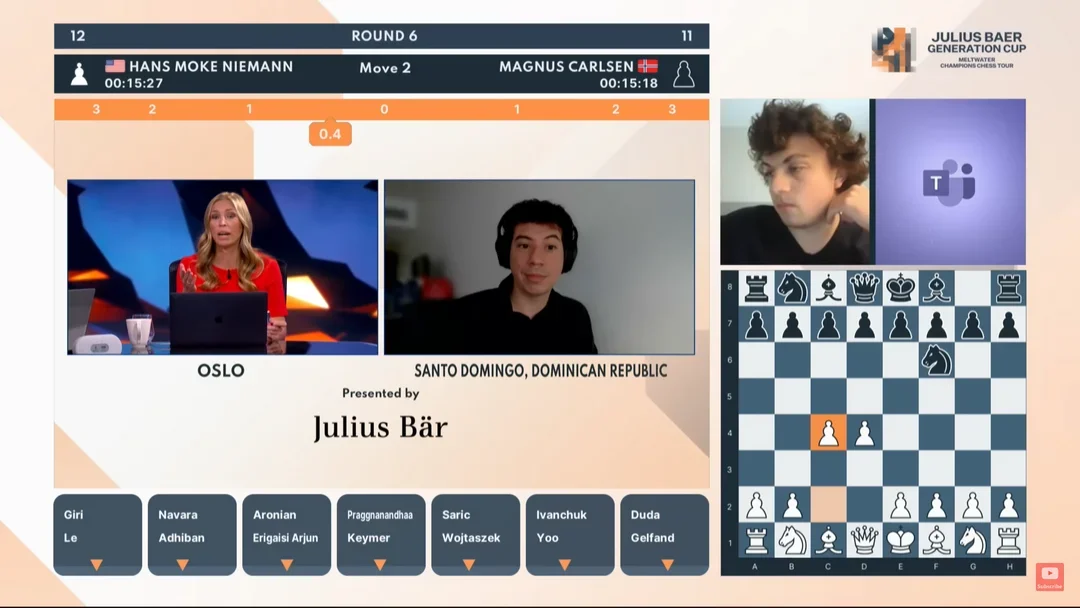

Any hopes that the controversy would subside after the final moves were played in St. Louis were quickly dashed. Rather than play Niemann in their online Julius Baer Generation Cup game, Carlsen resigned after one move. Two days later, on September 21, Carlsen fired another shot in this new Cold War, avoiding direct comment but saying, “I have to say I’m very impressed by Niemann’s play, and I think his mentor Maxim Dlugy must be doing a great job.” Carlsen doubled down in a September 27 statement, where he detailed his belief “that Niemann has cheated more — and more recently — than he has publicly admitted.”

The shot at Dlugy was not an innocent jab. Once Niemann’s coach in 2014, Dlugy had long been suspected in elite circles of online fair play violations. These charges were substantiated one week later when Chess.com provided emails and other materials related to Dlugy to a Vice.com reporter.

Why Chess.com leaked communications that all sides agreed were private is unclear. But more confidential emails were included in the October 4 Chess.com “Hans report,” a document that was also given to a Wall Street Journal writer ahead of publication. (Note that this was the day before the U.S. Championship began — where Niemann was scheduled to participate, a fact of which Chess.com must have been aware.) In that report, Chess.com claimed evidence of more online cheating, and more recent cheating, than Niemann had admitted to in his interview.

About over-the-board cheating, the report was equivocal. While there was “no direct evidence” of foul play in the Sinquefield game, Chess.com nevertheless claimed that the win over Carlsen was “suspicious.” Their decision to re-ban Niemann came after the Carlsen game, and in light of the suspicions it raised.

This is a key point. There is no evidence that Niemann cheated over-the-board. All of the amateur attempts to prove malfeasance were flawed, while both anti-cheating expert IM Kenneth Regan and the Chess.com report itself cleared Niemann’s over-the-board performances. So why did Chess.com decide to trust Carlsen’s “vibe check,” for lack of a better word, and re-suspend Niemann’s account? This has never fully been explained.

On October 20, Niemann filed a defamation lawsuit against Carlsen, Chess.com, Nakamura, and Rensch himself. Since then, every filing and motion nudges the controversy back into the public eye. The New York Times devoted the front page of their Sunday Business section to the saga on December 4, and the NPR program “Here and Now” had the co-author of that story, Dylan Loeb McClain, as a guest on December 12.

And in perhaps the ultimate sign of the impact this scandal had on the broader cultural landscape, “Saturday Night Live” name-checked the Hansen / Musk theory in a game-show skit on December 17.

This is the first feature I’ve written for Chess Life in some time, and honestly, it wasn’t a lot of fun to work on. The sad truth is that no one comes off well in its telling. There are no winners here, only various grades of losers.

But this is as important a story as it is unpleasant in its content. I suspect that when we look back at “l’affaire Niemann” a few years down the road, it will, in fact, appear as an inflection point in the history of our game. Carlsen’s anti-Niemann gambit may have been factually false, but at root, I think it was a desperate attempt to grapple with the threat of cheating in competitive chess.

Engines aren’t going away. They’re getting smarter, and the devices they run on are getting smaller. Every chess organizer, and every chess organization — including this one — must remain vigilant to protect the integrity of their events.

There’s another part to the story here, and one that hasn’t really been discussed. That’s the growing influence of Chess.com and online chess on the modern chess landscape.

At launch, the Chess.com Global Chess Championship was called the Chess.com World Chess Championship. While the name was quickly changed, that it was initially designed to be a “World Championship” could be an indication of Chess.com’s ambition. This was perhaps less of a concern while it was in direct competition with Chess24 and Play Magnus; now, having bought out the competition, Chess.com stands alone.

What is Chess.com’s place in international chess governance? Should a ban on their platform be a reason for FIDE to investigate a player? And does a commercial relationship with one or more competitors, or a commercial interest in their success, lead to irresolvable conflicts of interest?

Such questions are far beyond my prognosticative abilities. For now, both Carlsen and Niemann continue to ply their trade, both online and in-person, and the next chapter in their saga may have already taken place by the time you read these words.

The World Rapid and Blitz Championships are scheduled for late December in Kazakhstan, with both Carlsen and Niemann listed as competitors. What happens if they are paired? Will Carlsen forfeit again out of principle? Will he try to let “the chess speak for itself” and take his chances over-the-board?

Perhaps most significantly: what will happen the next time he’s paired with someone else — someone not named Hans Niemann — whom he suspects of foul play?

And what will happen if other players follow in Carlsen’s footsteps, or even take the lead?

Postscript:

Since this article went to press in mid-December, the World Rapid and Blitz have come and gone without controversy. Carlsen took top honors in both the Rapid and the Blitz, while Niemann — swarmed by cameras and spurning journalists — struggled in both events.

Round 8 in Rapid: Hans Niemann vs Parham Maghsoodloo (draw) pic.twitter.com/8Zn59GVPBj

— David Llada ♞ (@davidllada) December 27, 2022

One potential landmine was averted: the two were not paired in the Rapid or the Blitz, leaving the ball still firmly in Carlsen’s court as to how he will act the next time they meet in competition.

Filings and updates in the lawsuit continue, with an amended complaint from Team Niemann coming in early January. Some of the hyperbole was stripped out by Niemann’s lawyers, while some juicy new accusations were inserted, including the claim that Carlsen paid his teammates to shout anti-Niemann slurs at the European Club Championships in October.

Having completed its takeover of the various Play Magnus properties just before Christmas, Chess.com has announced "a new beginning" with the launch of its 2023 Champions Chess Tour. This year-long event, boasting a $2 million prize fund, is being promoted as "the richest and most prestigious annual circuit in chess history," and with its inclusion of GM Magnus Carlsen, as having "all of the world's best players... involved." The contrast with FIDE and its world championship cycle is unmistakable.

Finally, in one final reminder of the enduring relevance of this saga, Niemann himself appeared as an answer on Jeopardy! on January 23.

At least there’s one Jeopardy question 99% of all chess players would get right. #jeopardy #trivia #chess pic.twitter.com/afoWbjivz1

— Maurice Ashley (@MauriceAshley) January 24, 2023

How I would have loved to hear Alex Trebek ad-lib around that one.

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (8)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)