Editor's Note: This article was originally published in the August issue of Chess Life magazine. Consider becoming a US Chess member for more content like this — access to digital editions of both Chess Life and Chess Life Kids is a member benefit, and you can receive print editions of both magazines for a small add-on fee.

Download a printable version of this story here.

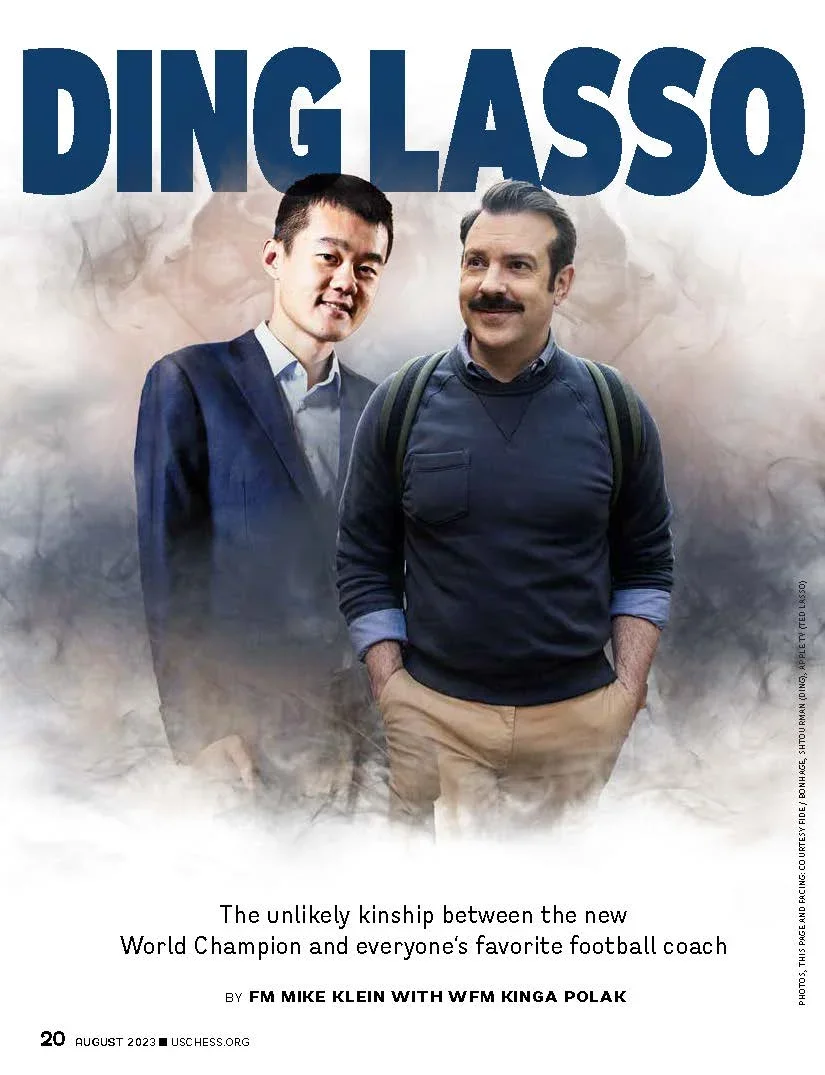

Compared to the past decade’s matches, a large swath of fans went into this world championship feeling tepid interest. The match was not in a major world city, and many regarded it as a battle for the world’s second-best player. That slowly changed over the course of April. At first, the flurry of decisive results piqued interest. Then, slowly, the candor of the eventual winner won over fans both on-line and in-person. When we see the current champion, we now see ourselves.

Ding Liren was much more forthcoming and candid than any other world championship player in our lifetime. Gone was the mercurial Magnus; in his place was the thoughtful, quiet Ding, a player that few had heard speak in depth before this match. And what we heard, we liked.

Ding’s traits were our traits. For the first time in a long time, chess amateurs could actually relate to a 2800 — the fear, the uncertainty, the disappointment, and ultimately, the triumph. (Now, of course, it occurs to me that if Ding had lost the tiebreaker, that might have produced an even more apt mirror of ourselves, depending on current feelings about one’s own life and chess abilities.)

I was on-site for the match, doing live reporting for chess.com and chesskid.com, and as a globetrotter with an Apple+ subscription, some of my evenings were spent in search of new entertainment. (Not to say anything bad about the nightlife in Astana, of course.) Some friends suggested I check out Ted Lasso, whose third and final season had premiered a few weeks before Nepomniachtchi’s e-pawn made its first venture forward.

Suddenly I found myself confusing the soon-to-be world-champion with the eponymous “football” coach from Kansas.

What the world saw in those emotional games and plainspoken press conferences was certainly Ding Liren, but to me, plowing through episodes on sometimes-questionable wifi, it was also Ted Lasso castling and charming the room.

The surface-level similarities are plain. (Don’t worry — we will minimize serious spoilies for those who haven’t seen everything yet.) Both become known to the world after a romantic breakup — Ding split with his girlfriend before the match, while Ted slogs through an emotional divorce. Both are also trying their best in press conferences using a version of English that sometimes bewilders them. For example, recall this trans-Atlantic linguistic mashup from the second episode:

Ted: “If I were to get fired from my job where I’m puttin’ cleats in the trunk of my car?”

Coach Beard: “You got the boot from puttin’ boots in the boot.”

But the television show serves as a much deeper allegory to what we saw unfold in Astana. The reason audiences engage with Ted is the same reason we feel an affinity with Ding. It’s not the results, but the process, the struggle, and the willingness of the protagonists to be open about everything they are experiencing. Ted uses intuition and emotional intelligence to make his decisions, and so too does Ding, his real-life counterpart.

Witness some of the overlap between Ted Lasso and Ding Liren, as seen in quotes from the show and the post-match press conferences:

Ted: “You know what the happiest animal on earth is? It’s a goldfish. You know why? Got a ten-second memory. Be a goldfish.”

Ding: Not only did he recover immediately from losses and multiple match deficits to continuously get back to even in the match, but he also said, “I thought... at one point I feel it’s totally silent in the playing hall and ... I didn’t feel anybody watching the games. It seems to be a very important game but I didn’t feel it at all.”

Ted: “Hey, here’s a little trick of the trade. Just make fun of yourself right off the bat, a little joke. Folks will love that.”

Ding, explaining why there were so many more decisive games than in recent world championships: “I guess the reason is maybe we are not that professional than Magnus.”

Ted: “I want you to be grateful that you’re going through this sad moment with all these other folks. Because I promise you, there is something worse out there than being sad, and that is being alone and being sad.”

Ding, who was visibly unfocused during his pitiful round two loss: “Yeah, I would like to say to my friends, they helped me to deal with my ... emotional problems. Now I feel more comfortable ... One of my friends said to think about the things from the positive side. I think that’s the best advice for me during this tournament.”

Anxiety is a major theme in Ted Lasso, and both Ted and Ding originally dealt with their anxieties in similar ways: by running from the source in the middle of the competition. For Ted, this meant leaving the playing field. Ditto for Ding, who played much of the first two rounds from the player’s rest area.

In fact, Ding looked about as uncomfortable in the first two rounds as you will ever see a world-class player. (Here I recalled Ted on challenges: “Taking on a challenge is a lot like riding a horse, isn’t it? If you’re comfortable while you’re doing it, you’re probably doing it wrong.”) Ultimately, both learned coping mechanisms, and how to face their fears head-on. Not only did Ding camp out at the board much more in the remaining rounds, but after leaving the site hotel after round one, Ding returned to the St. Regis Astana, despite knowing he was greatly outnumbered there by Team Nepo.

But what about getting professional help?

Ted, when initially asked for his thoughts on therapy: “General apprehension and a modest Midwestern skepticism.”

Ding: “[My friends] talked to me and even suggested if I need a doctor, but maybe it’s not that serious.”

What about the “leaked” openings, where internet sleuths found games on chess.com and LiChess.org remarkably similar to some of Ding’s world championship efforts? The eventual world champion was not fazed by the discovery at all, downplaying their importance. Ted also has nothing to hide, asking some unhappy fans, “Why don’t you come watch training tomorrow? See for yourselves. We ain’t running a chocolate factory or Deutsche Bank. We got nothing to hide from y’all.”

Both use decision making that is much at least as intuitive as analytical.

Ted: “You just listen to your gut, OK? And on your way down to your gut, check in with your heart. Between those two things, they’ll let you know what’s what.”

Ding chose a large number of openings while at the board, which is almost unheard of at the world championship level. He even spent time on move number one in several games; for example, he only decided to play the French after the clock started and 1. e4 was on the board.

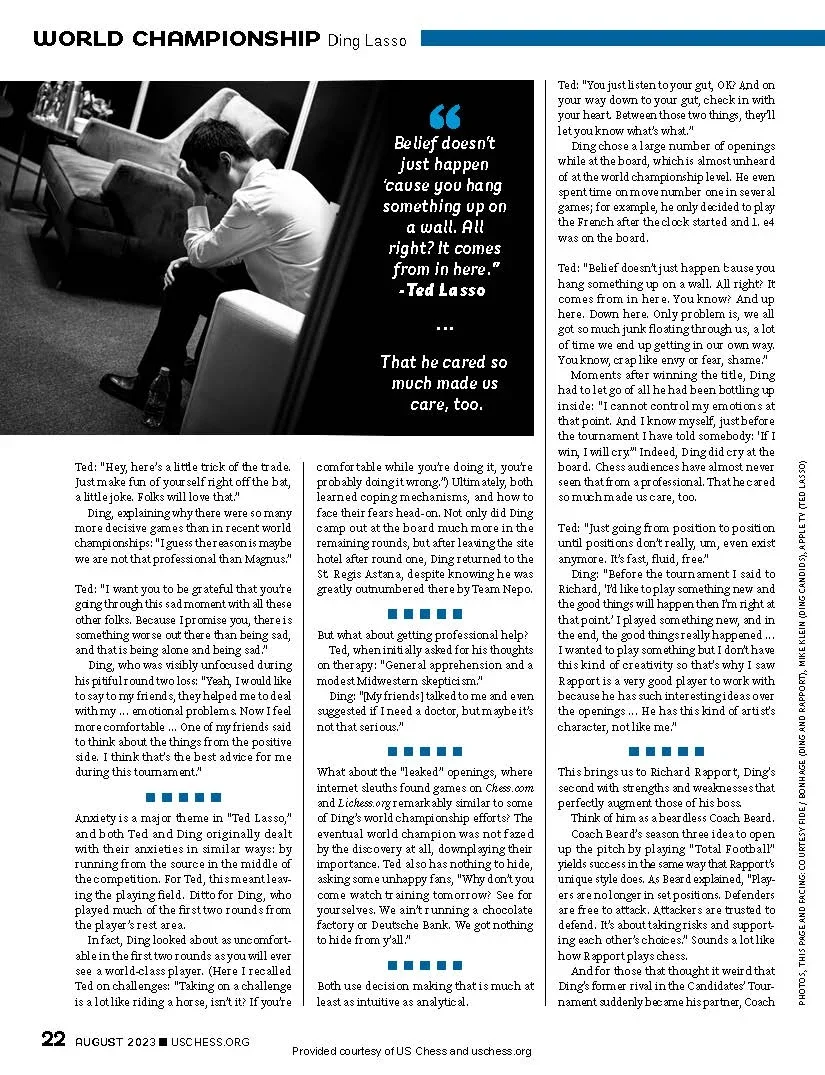

Ted: “Belief doesn’t just happen ‘cause you hang something up on a wall. All right? It comes from in here. You know? And up here. Down here. Only problem is, we all got so much junk floating through us, a lot of time we end up getting in our own way. You know, crap like envy or fear, shame.”

Moments after winning the title, Ding had to let go of all he had been bottling up inside: “I cannot control my emotions at that point. And I know myself, just before the tournament I have told somebody: ‘If I win, I will cry.’” Indeed, Ding did cry at the board. Chess audiences have almost never seen that from a professional. That he cared so much made us care, too.

Ted: “Just going from position to position until positions don’t really, um, even exist anymore. It’s fast, fluid, free.”

Ding: “Before the tournament I said to Richard ‘I’d like to play something new and the good things will happen then I’m right at that point.’ I played something new, and in the end, the good things really happened ... I wanted to play something but I don’t have this kind of creativity so that’s why I saw Rapport is a very good player to work with because he has such interesting ideas over the openings ... He has this kind of artist’s character, not like me.”

This brings us to Richard Rapport, Ding’s second with strengths and weaknesses that perfectly augment those of his boss.

Think of him as a beardless Coach Beard.

Coach Beard’s season three idea to open up the pitch by playing “Total Football” yields success in the same way that Rapport’s unique style does. As Beard explained, “Players are no longer in set positions. Defenders are free to attack. Attackers are trusted to defend. It’s about taking risks and supporting each other’s choices.” Sounds a lot like how Rapport plays chess.

And for those that thought it weird that Ding’s former rival in the Candidates’ Tournament suddenly became his partner, Coach Beard has an answer for that, too. “You know, we used to believe that trees competed with each other for light ... We now realize that the forest is a socialist community. Trees work in harmony to share the sunlight.” Chess fans suddenly had three daily events to follow — the game itself, the post-match press conference, and the daily Ding-Rapport embrace.

This was more than just a second. This was a quirky but heartfelt fraternity of two. Ruff ruff — Ding had found his Diamond Dog.

There’s much more to the friendships than work talk, of course. Ding/Rapport and Ted/Coach Beard also share a fondness for classic bands when talking to each other. Musical references fly fast and furious on Ted Lasso, and just like Rapport’s daily fashion statements, Trent Crimm’s t-shirts were the stuff of Reddit legend. (Unassociated: do I have to forever announce myself as “Mike Klein, chess.com” now?) Similarly, Ding and Richard share a fondness for “80s music,” with Ding specifically mentioning “Blowin’ in the Wind” by Bob Dylan as a Team Ding favorite.

Could Nepomniachtchi be included in this Lasso-look-alike analogy? Although in some hair styles he looks a little like Zava, perhaps he is more closely aligned with Nate, at least in one way. While Ted’s fellow Premiership manager tries to out-duel him on the field, away from the stadium Nate shows clear fondness for the man he is trying to beat. So too did Nepomniachtchi: following round five, Ian admitted about Ding: “After the rest day, I already missed him.” When have you ever heard that at a world championship?

So where are we now? The world no longer has Magnus, perhaps the greatest player of all time, as the title holder. Many thought we’d inherit a paper champion, but Magnus’ departure actually helped pave the way for an even more relatable king. A king who bucked all the world championship norms, like secrecy and insularity. A king who reads Michel Foucault and channels Albert Camus in times of distress. A king who admits his weaknesses, a king who fails, a king who needs encouragement, a king who needs his friends.

In short, a king like Ding.

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (6)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)