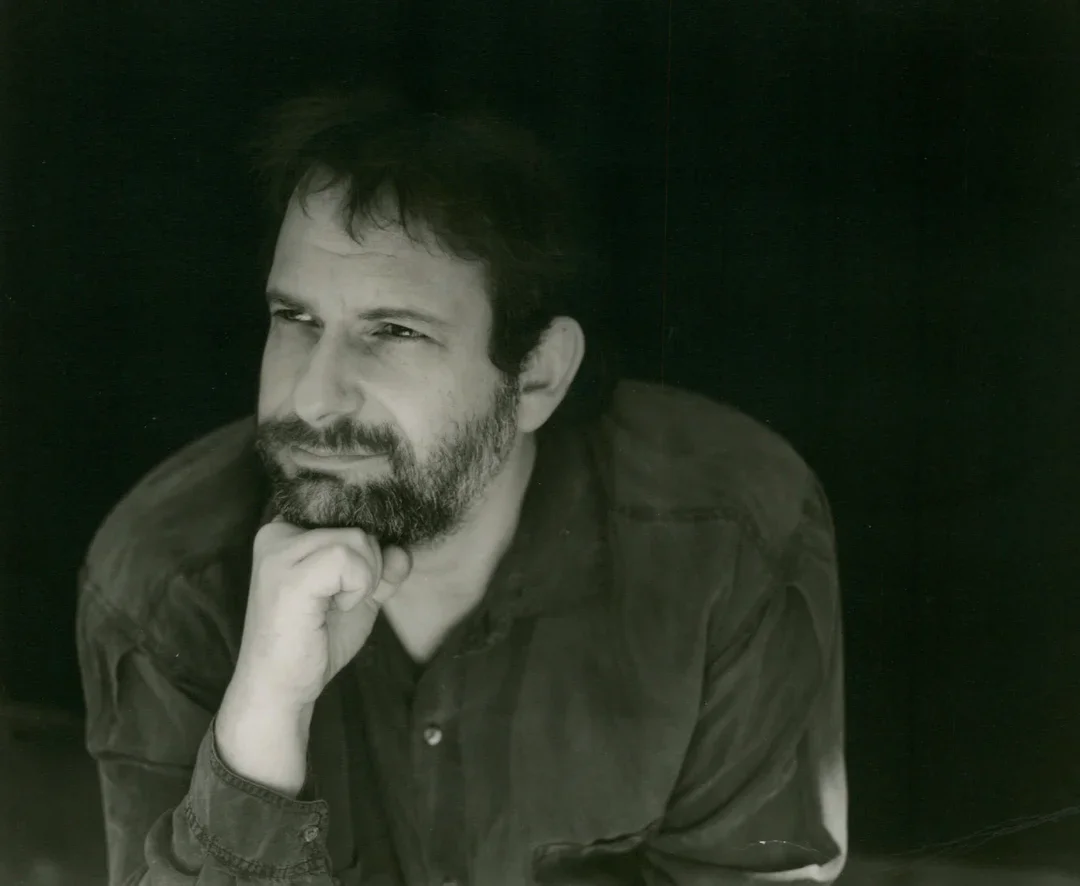

Few individuals have had as great an influence on American chess as IM Jeremy Silman, who died on September 21 in Los Angeles, California. The cause was complications from primary progressive aphasia frontotemporal dementia.

Born on August 28, 1954, in Del Rio, Texas, Jeremy’s family moved around a lot when he was young as his father was in the military. It was only when they settled in San Diego in the late 1960s that Jeremy started to play chess. He was not a prodigy, as his first rating of 1142 on the September 1968 USCF rating list makes abundantly clear. After Jeremy graduated from high school, he served a short stint in the US Army. He did not start to make serious progress as a chess player until late 1973, when he moved to San Francisco and roomed with then-U.S. Champion John Grefe and Dennis Waterman, a national master.

This was a golden time for Bay Area chess, one that would extend into the early 1980s. Tournaments were held nearly every weekend, offering plenty of strong opposition. Future U.S. Chess Hall of Famers and GMs Walter Browne, Larry Christiansen, Nick deFirmian, and James Tarjan were regular competitors.

Jeremy, who had fond memories of this time, blossomed in this environment, becoming a master in January of 1975 at the age of 20. Today this would not be remarkable as standards have risen markedly, thanks in part to technological advances and players starting at an earlier age, but at the time this rating put him in the top ten juniors in the country.

Jeremy kept plugging away, reaching 2400 in September of 1980, and 2500 roughly a year later after tying for first in the U.S. Open in Palo Alto, California. He reached a then-career high of 2556 in the summer of 1982, but soon began a period of personal and financial struggles that lasted almost five years. His rating nearly dropped below 2400, but Jeremy persisted in his dream of life as a chess professional.

He had always enjoyed writing and in the mid-1980s began to author a number of opening works for Chess Enterprises and Chess Digest. Writing these pamphlets was not particularly lucrative but they offered Jeremy a chance to showcase his talents as an analyst.

He produced number of important theoretical novelties in those pre-chess engine days, including:

Another was in the Sicilian Dragon, when Black’s doubled a-pawns in the ending are compensated by good counterplay on the queenside, in particular the use of the c4-square:

During 1985 Silman finished the first edition of what would become his magnum opus, How to Reassess Your Chess, which is now in its fourth edition. The almost-200-page long manuscript he submitted to Bob Long of Thinker’s Press was not typed but handwritten — Jeremy had incredibly neat penmanship. This book is where he first introduced the theory of imbalances in chess that became a hallmark of his teaching.

Not long after finishing How to Reassess Your Chess, Jeremy moved to Los Angeles to serve as the editor of the bi-weekly publications Players Chess News and Theory and Analysis. This was the start of Jeremy’s rebirth, both personally and chessically.

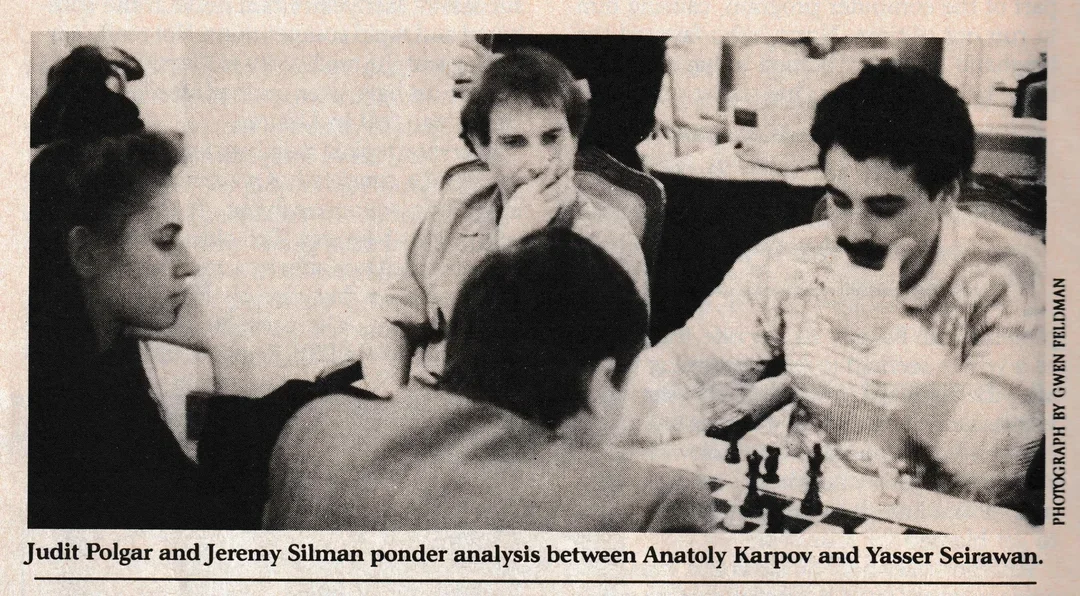

He made his long overdue final IM norm in 1987 and began the start of a 36-year marriage to Gwen Feldman that ended only with his death. Gwen, a professional in the publishing business, would produce the final edition of How to Reassess Your Chess along with other classics including The Amateur’s Mind, Silman’s Complete Endgame Course, and Pal Benko: My Life, Games, and Compositions. Several of Silman’s books have been translated into foreign languages, including French, German, and Chinese.

Jeremy peaked as a player in the late 1980s and early 1990s. During this period, he tied for first in the National Open and American Open, and he defeated Jack Peters, one of the strongest IMs in the history of American chess with a FIDE rating of over 2500 for close to two decades, by a score of 3½-½.

Jeremy reached his peak US Chess rating of 2593 on the May 1990 rating list. He didn’t advance further, or seriously pursue the grandmaster title, in part because he never enjoyed overseas travel. In those days this was necessary for players pursuing norms.

Although Jeremy had begun his retirement from the tournament arena, he continued contributing to chess through his writing and lecturing for the better part of the next three decades. Besides his books, he was a columnist for Chess Life and later for Chess.com. He also was the chief commentor for the U.S. Championships of 2000, 2002, and 2003 and served as the guest lecturer for the American Open for over two decades.

Jeremy’s lectures were always well received, due to his ability to be both funny and instructive. These were the same qualities that also made his books so popular. He knew his audience, and his listeners and readers often felt he was speaking directly to them. Before Silman, most instructional books were aimed at either beginners or masters. His target audience of players rated 1200 to 2000, which had previously been underserved, gobbled up his books.

Regrettably none of Jeremy’s public lectures have been preserved, but his work for The Great Courses ensures that a visual and aural record of his skill as a chess educator has been saved. With over 100,000 courses sold, it also serves to demonstrate just how deeply Silman has affected the lives of chess players around the globe.

This is especially true if one takes into account that that Jeremy’s seven titles published with Silman-James Press have sold over 600,000 copies. That isn’t counting the number of individuals who bought copies secondhand or who checked out Jeremy’s books from their public libraries.

This, coupled with the roughly 30 other books he authored (including a five-volume best-selling beginner series with Yasser Seirawan), The Great Courses work, his columns for Chess Life and Chess.com, his pioneering work for the early electronic chess instruction company Chess Mentor, and his contributions to Inside Chess, Northwest Chess, Player’s Chess News, and Theory and Analysis, demonstrate how Jeremy impacted — and will continue to impact — generations of chess players. That’s not counting the number of non-chess players he reached serving as a chess consultant for the Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone movie or prominent TV shows such as Monk, Criminal Minds, Malcolm in the Middle, and Arliss.

That’s not a bad legacy to leave.

As part of this remembrance, Donaldson has selected three of Jeremy’s best games, each with Silman’s own notes. The print version of this obituary will feature Donaldson’s analysis of one of Jeremy’s favorite games, a brilliant victory over IM Cyrus Lakdawala from 1989. ~ed.

Editor's note: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Silman did not begin making serious progress as a chess player until 1983. The text has been updated with the correct year (1973).

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (13)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)