Editor's note: This story first appeared in the April 2024 issue of Chess Life Magazine. A pdf is available courtesy of US Chess.

Consider becoming a US Chess member for more content like this — access to digital editions of both Chess Life and Chess Life Kids is a member benefit, and you can receive print editions of both magazines for a small add-on fee.

Happy birthday, Jude.

FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2024

12:10 p.m.

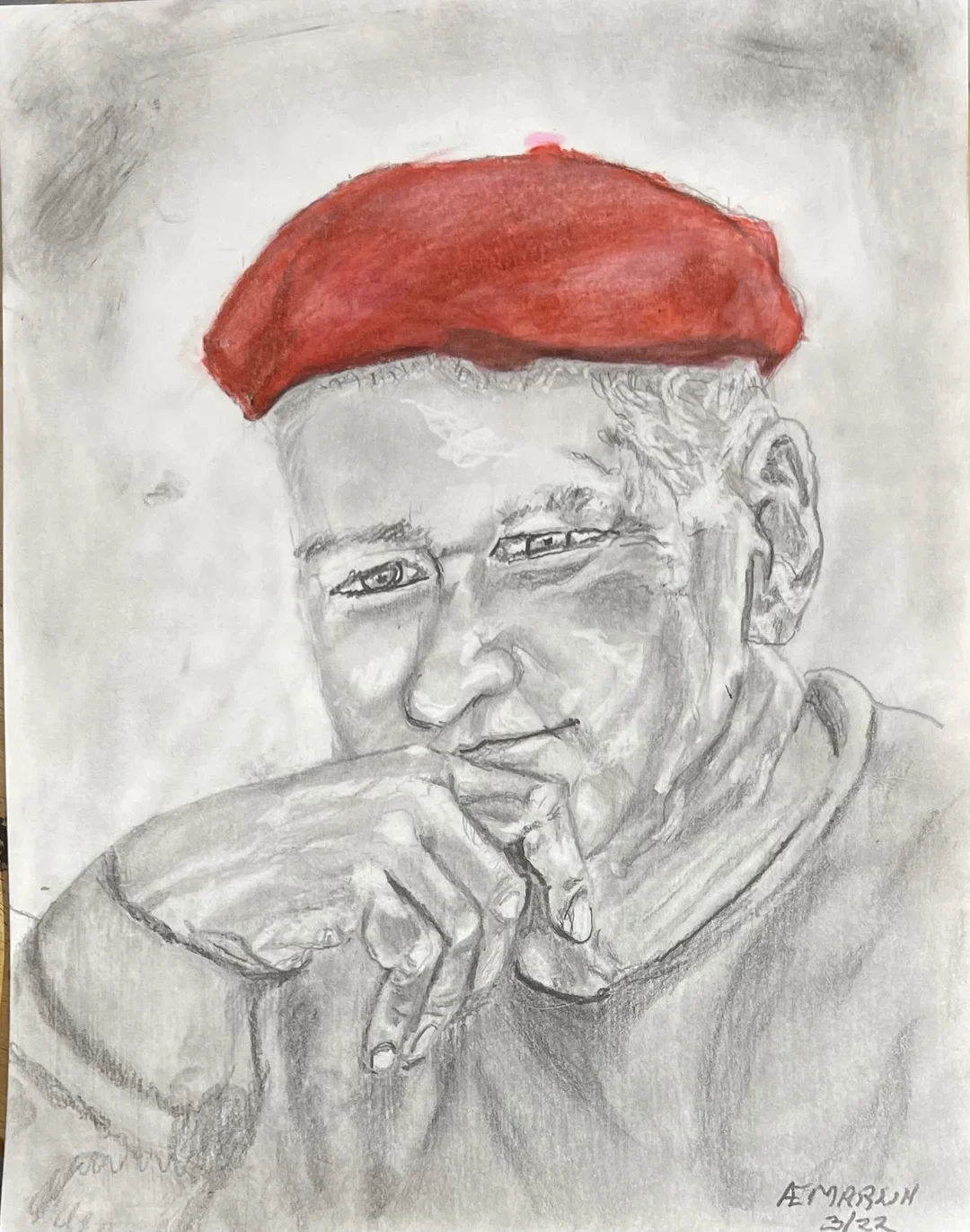

Jude Acers’ red beret floats above the food shelves at the Quarter Grocery & Deli on Burgundy Street in New Orleans’ French Quarter. A round, open, improbably youthful face comes into view. Then a booming voice.

“Are you ready for your first lesson?”

There is no reaction behind the po-boy counter, where they’re accustomed to Jude. This is his neighborhood grocer and it’s where, when I asked Jude if I could join him for a full day at his World Chess Table, he agreed to meet.

Jude agreed to this, like he does everything, in his own fashion. When away from his table, Jude’s preferred mode of communication is email. And more than anyone I know, he has found a way to type an email that perfectly matches the way he speaks. Here’s how he responded:

MR. MICHAEL TISSERAND BLOOD HOUND MEDIA REPORTER/ WORLDWIDE MEDIA FEED reporter WHO WROTE THE monster 2500 word front paged JUDE ACERS MEMORIES NEW ORLEANS PICAYUNE ADVOCATE article “THE FISCHER KING’,…WELCOME!.AT YOUR SERVICE KIND SIR! 12 NOON FRIDAY WE START QUARTER DELI … 836 BURGUNDY STREET!! All will be revealed!

I’ve known Jude Acers (pronounced like “acres”) for 20 years, ever since my daughter first played a simul with him in her elementary school cafeteria. He’s given his time to scholastic chess events I’ve organized and, as he noted, I once wrote a story for the local newspaper about the time he drew Bobby Fischer during Fischer’s visit to New Orleans in 1964, when Fischer was 21 and Jude was 20.

And now, walking out of a grocery store with Jude Acers into a bright New Orleans afternoon, I’m about to receive the day’s first lesson. This one is in survival.

12:16 p.m.

Turning from Burgundy Street onto Dumaine, Jude walks with short, quick steps on a brisk, zig-zag route toward Decatur Street, where the World Chess Table waits to be assembled. Then he quickly pivots. “Number one,” he says, “have everything tied to your body. I needed this twice in the past 20 years.”

He pulls out items from his pocket to display that each is attached by yarn. Then he lifts his coat. “At six or seven there could be wind chills. Body heat is tremendously important for a professional player.”

He fixes me with his eyes. “For these lessons your readers will owe me for all time.”

We keep walking. Jude turns 80 years old this month on April 6, and I am working hard to keep up with his pace. He is talking about the importance of vitamins and fish oil and resveratrol, and telling me where in New Orleans you can get the best deals for each. He raises a finger. Coffee, he says, is “absolutely mandatory.”

But more than anything else, Jude says, walk everywhere. He hasn’t been in a car in more than a year.

Long ago, Jude swore off drinking and narcotics. “I’ve been to parties where I was the only one with clothes on and everyone was doing heroin,” Jude says without further elaboration.

As he says this, we pass two early Mardi Gras revelers. One is dressed as a Spanish matador and the other as a Southern plantation belle. They look at us curiously.

12:25 p.m.

Jude stops at Matassa’s Market for The New York Times but there’s a line and he doesn’t have time for that. We move on to another shop, Jude directing us into the middle of Dauphine Street. This is another lesson. “Walk in the middle of the road. These sidewalks aren’t made for walking. At my age I can’t fall.”

It is the only time today he will make any concession to his age, even if this particular concession is to walk down the middle of French Quarter streets.

“And never, ever cross at the crosswalks. That’s where you die.”

12:40 p.m.

Jude now stands in the middle of Ursulines Street, having stopped just a block short of the World Chess Table. His booming voice cascades off the stucco walls of the centuries-old Old Ursulines Convent. Both the building and Jude seem made for this place, like they could not exist anywhere else. Jude points out a wooden doorway below an iron-laced balcony. Here is where he found Wi-Fi during the pandemic.

We make it to Decatur. Jude suddenly ducks into a store called Everything New Orleans, one of many shops here selling shirts, Hurricane drink mixes, stuffed alligators, and Mardi Gras beads. Buildings in the French Quarter can hold more secret passages than a haunted house, and Everything New Orleans is no exception. Jude strides in and heads straight to the back, where he vanishes into a hidden brick-lined alley. He reaches into a corner of the alley and pulls out wooden boards and bags of chess pieces, and strides out.

“I’m 42 years here,” he says. “They also hold my mail.”

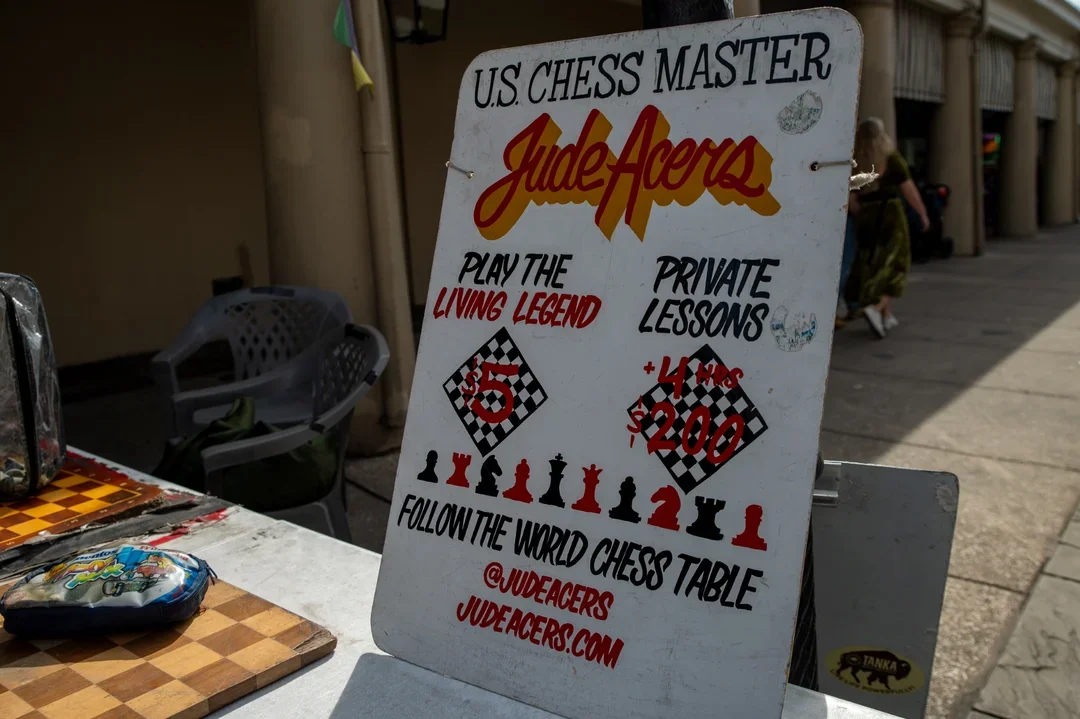

A scuffed white folding table is waiting for us, fastened to a column with a bicycle lock. Before unlocking the table, Jude straightens and points to a seafood restaurant on the corner.

“The French Market Restaurant feeds me every time I walk in, which is 100,000 dollars.”

Jude has a street hustler’s habit of naming a price for everything, and an artist’s habit of tossing numbers aside when they get in the way.

“I rolled the dice,” he says, setting down his bags. “Look at me. I’m in the last years of my life in perfect health doing exactly what I want to do.”

12:52 p.m.

On the way out of Everything New Orleans, I had offered to carry one of Jude’s bags. He held up one hand as if to signal for a complete stop.

“Do not touch my set up,” he said. “This is my exercise.”

Now he effortlessly lifts his table and snaps it into place. I will hear later that he purchased it a few years ago at a Walmart and pushed it to Decatur Street on a luggage rack. I look up the distance. It’s a two-and-a-half-mile walk.

“Notice three chairs at once.” Jude lifts the plastic molded chairs and scatters them into their places. One for himself and another for his opponents. “Always have the sun shining in your opponent’s eyes,” he says like it’s a secret, but it’s something he’ll tell his opponents about all day.

“And this,” he announces, holding up the third chair, “is the Baylee chair.”

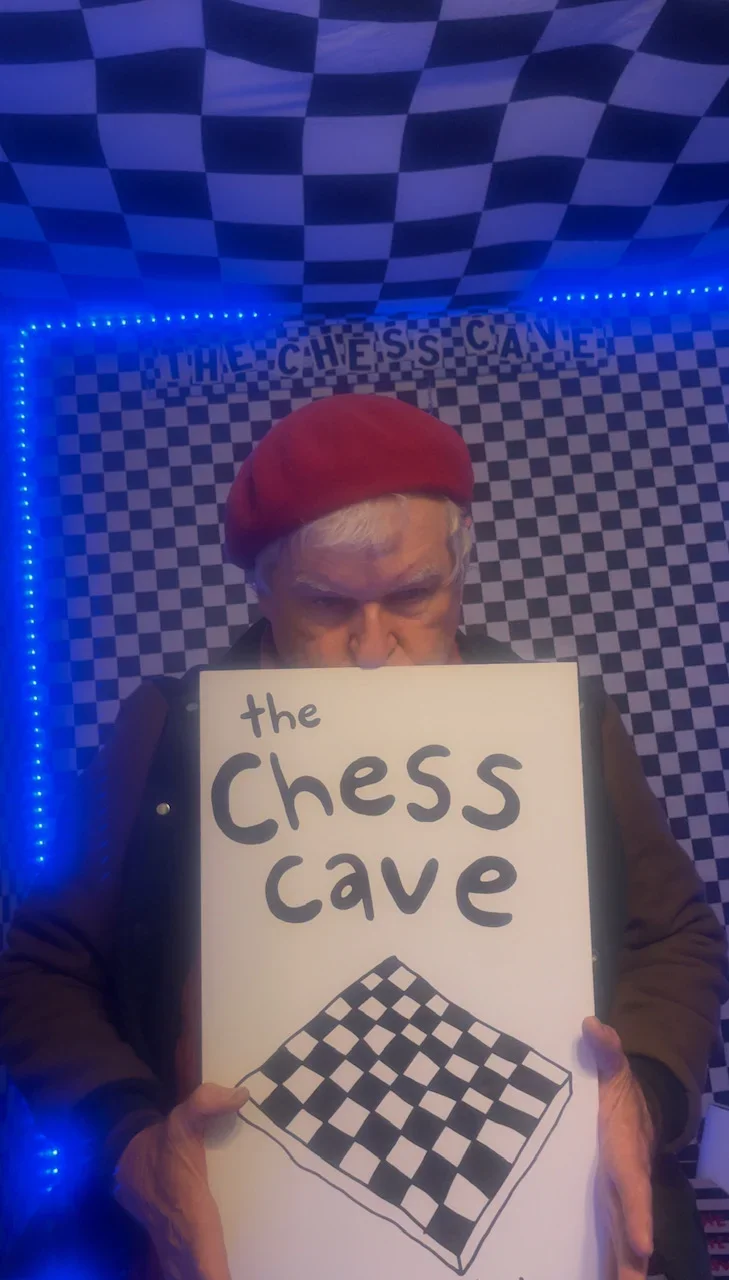

Baylee Badawy is a local promoter and social media whiz who has done work for the New Orleans Jazz Museum and the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. She also has devoted herself to the continued well-being of Jude Acers, whom she met when she began visiting his table during the quiet days of the pandemic. Since then, she’s improved Jude’s living quarters as well as co-founded a nonprofit called “The Chess Cave,” a surreal closet of a room set off a French Quarter street and decorated floor to ceiling like a chess board. There is room in The Chess Cave for a table and two chairs, and little else. She describes it as a safety net for Jude.

Baylee is the latest in a line of people who fulfill this role for him. Jude often sponsors matches with cash prizes provided by someone he only identifies as an “anonymous benefactor.” He travels overseas for tournaments with the same unnamed assistance.

But Baylee’s not in town, Jude says. She’s off in Las Vegas with her grandfather. She’s helping him gamble or they’re seeing the Super Bowl. I can’t quite get the story straight. In the meantime, he allows me to sit in the Baylee chair.

1 p.m.

It’s now one o’clock sharp and Jude is in position for the day. I ask if he always starts at one. “If I feel like it,” he says.

Jude notates his games but not his days, making the exact origins of the World Chess Table unclear. Derek Bridges, the director of the new Jude Acers documentary The Man in the Red Beret, believes that Jude first set up his table in the summer of 1981, making this summer its 43rd year.

Derek’s movie is as intimate a portrait of Jude as anyone is likely going to be able to make. It follows him through a painful childhood with an alcoholic father and a mother who, suffering from mental illness, died when Jude was young. “Chess saved me,” Jude says, and in this, he does not seem to be exaggerating. As a student at Louisiana State University, chess gave him celebrity status. He moved to northern California and traveled the country giving exhibitions. In the mid-1970s, he twice held the world record for most games played simultaneously — 117 in Oregon and 179 in New York.

By 1978, Jude had returned to New Orleans. The newspapers reported that he was threatened with a knife in the French Quarter’s Pere Antoine Alley. Jude held off the robber, who escaped empty-handed.

That year, Jude played with a chess team based out of the city’s Maple Leaf Bar, a legendary music club. Soon, Jude was appearing in more music clubs than many musicians, including nights on stage at Tipitina’s to play blindfold matches. In 1979, the local newspaper caught up with Acers at another storied club, the Dream Palace. Reported the newspaper: “Acers is a fixture at the Dream Palace, where the owners allow him to come and go as he pleases. They have adopted him, much as he has adopted them.”

In 1983, Jude was listed as an attraction at a French Market festival, along with a balloon artist, a mime, and a troupe of Hellenic Dancers. He appears to have chosen his Decatur location both for the visibility and for an overhanging roof in case of rain.

It was around this time that Jude heard himself pointing out a local chef as a man in a black beret. Inspired, he seized on the idea of wearing a bright red beret, distinguishing himself in the most colorful of crowds.

Why did he pick this spot for the World Chess Table? In 1981, Jude said in an interview with television reporter Eric Paulsen that he likes to play chess in unusual places. “In addition to being a great, great, great player,” Jude told Paulsen, “I also have the ability to create magic in the middle of the desert.”

1:10 p.m.

A woman from a nearby praline shop comes to the table with two large plastic cups filled with vanilla ice cream. It is the first of many sudden food appearances at the World Chess Table.

Photographer James Cullen has also shown up to take pictures for Chess Life. “Shoot as many as you want,” Jude instructs. “Shoot for your private collection. They’ll be worth millions of dollars when I’m gone.”

1:29 p.m.

Mardi Gras traffic is well underway on Decatur Street. For the rest of the day, a steady line of cars slowly proceeds by Jude’s table. Some drivers wave. A few shout out. Nearly all stare.

A vendor walks by Jude, pushing a cart of hot tamales. “I love you forever,” Jude calls out to him.

Then he offers another life lesson: Always tip. In 1989, Jude says, someone showed up at the table with a suitcase filled with 100 dollar bills. They played chess all day. Jude received a 100 dollar tip each game. When the suitcase was empty, the man left.

2:03 p.m.

The World Chess Table is slow to start today. Nearby, a woman is holding a small ladder on which seven parakeets are perched for pictures and tips. It’s a slow afternoon for parakeet pictures, too. She comes over to the table and plays a game with Jude, balancing the parakeet ladder on the table. Jude quickly wins but enthusiastically talks her up — as he talks up all his friends — saying the parakeet lady is usually a very strong player.

2:17 p.m.

There is a particular stance that new arrivals to the World Chess Table assume when they are hoping to play Jude. It is polite and expectant and a little unsure about what they are getting into. I’ve seen the same stance from people waiting to go into a confession booth.

Currently assuming the stance is a young man who just parked a Segway near the table. He wears dark sunglasses and has long sandy hair flowing out the back of a San Diego cap, and he’s holding a 16-ounce can of Pabst Blue Ribbon. He introduces himself as Sam, and he used to run Segway tours in New Orleans. Now he’s working to start his own company in California.

For years, Sam would wheel his tours past Jude’s table. A couple years ago, inspired by “The Queen’s Gambit,” he started playing chess more seriously. Now he’s back in New Orleans for Mardi Gras and to play Jude, but not in that order.

“I had a customer take a lesson from you,” Sam says, eagerly taking his seat. “He said you’re a really smart guy.”

The Louisiana sun beats down on Sam’s face as he reaches into his pocket for a crumpled five-dollar bill.

“I know I’m dealing with an expert player here because he brought sunglasses and a billed cap,” Jude says. “Double protection.”

2:25 p.m.

Jude starts to narrate his own play, letting Sam know what he’s doing and why he’s doing it. The game continues until Sam looks down at his position. “Tripled pawns,” he says, already sensing defeat.

Jude builds him up by giving him one of his highest compliments: a new nickname. For the rest of the day, Sam will be Young Upstart.

2:32 p.m.

A group of Vanderbilt University students clusters around the table. They start peppering Jude with questions.

“Do you take Venmo?”

“Would you mind telling us your rating?”

“Who’s the best player you ever played?”

Jude answers that last one. “Bobby Fischer.”

“You played Fischer? Holy s---!”

Jude looks away from them. Now into his second game with Young Upstart, he recites a list of chess books. Young Upstart writes them all down. The students keep watching. One says he started playing because of “The Queen’s Gambit.” The other is a fan of GothamChess on YouTube. They are all at college together but aren’t on a chess team. They mostly play online.

“Only one in 100 people play a real person,” Jude says. “So I’m actually a novelty.”

“Has anyone ever beaten you here?” the student asks.

“Sir!” Jude springs up and walks around the table. “How are people with high breeding asking a question like this!”

He resumes his game with Young Upstart. The students watch for a while longer, then fade away.

“People talk themselves out of playing every day,” Jude says.

2:47 p.m.

A man crosses the street and walks up to the table. He drops off a bag of shrimp po-boys and walks back across the street with no explanation.

2:48 p.m.

I’ve always considered Jude Acers to be doubly renowned: first as a chess player and, second, as a French Quarter icon.

Like the late sousaphone player Tuba Fats in Jackson Square, or the alive-and-swinging clarinet player Doreen Ketchens on Royal Street, Jude has staked out a spot of French Quarter property that he doesn’t own legally, but owns in every other sense of the word.

Like those musicians, Jude is larger than life. But as a character, he seems to me to rival the legendary Ruthie the Duck Girl, who was known for roller skating through the Quarter accompanied by a varying number of ducks.

I’m not sure how Jude will like the comparison, but I ask him. His eyes light up.

“I am Ruthie!” he says. “I consider her to be the greatest feature attraction of the French Quarter in the past two hundred years. Not even Paul Morphy could compare!”

2:50 p.m.

Jude is now giving Young Upstart package deals on games. He announces that his next opening will be the Richter-Veresov. It’s one of his favorites and he quickly gains a pawn.

“I’m not like Morphy. I don’t give pawn odds,” Jude says, placing the pawn on his side of the board.

Eighteen moves later, Young Upstart drops a queen. He stares at the board.

“I was looking at that queen the entire f------ time,” he says. “But this is what I came back to New Orleans for.” He reaches into his pocket for another five-dollar bill.

3:10 p.m.

Young Upstart runs across the street for another 16-ounce Pabst Blue Ribbon.

3:14 p.m.

After Jude wins the next game, he shows Young Upstart an exchange that would have equalized it. Then he dramatically pushes all the pieces off the board, with a flourish equal to Ben Kingsley in his portrayal of Bruce Pandolfini in the movie Searching for Bobby Fischer. Jude noisily slaps pieces on the board and sets up checkmate puzzles.

“A lesson for the Young Upstart!” he announces.

This goes on for the next half hour. At one point, I can’t contain myself and I blurt out an answer. Jude holds up a hand. “Reporter Found Strangled in Alley,” he narrates. “With Chess Piece in Mouth.”

One of Jude’s lessons includes a zugzwang position. Young Upstart is unfamiliar with the idea. Jude shouts.

“Zugzwang!”

Young Upstart shouts back. “Zugzwang!”

Jude, louder: “Zugzwang!”

Young Upstart, louder still: “Zugzwang!”

They keep at it. Faces peer from the slowly passing cars.

“You just got a 50-dollar lesson!” Jude says.

“I’m so glad I came down here!”

3:47 p.m.

Jude asks Young Upstart how he started playing chess. He says he started as a child with his grandfather, who had a handmade chess set that dated back to his days as a colonel in Vietnam.

“Where do you get your confidence? Did you always like yourself?” Jude asks.

“I’ve always had self-doubt. It’s always been a thing for me.”

“But you don’t care if nobody else does it. You’re going to do it.”

“One hundred percent.”

Young Upstart stands up. “We don’t have guys like you in San Diego,” he says. “We have chess clubs. But nobody like you.”

They shake hands. Young Upstart then gets on his Segway and glides off.

4:06 p.m.

“Put this in your notebook,” Jude says to me. “605 million people are playing chess. That’s a United Nations survey.” He waits for me to write it down.

One of these 605 million, Stephen, now approaches the table. He’s holding hands with his wife, Nikki. They’re from Houston. He’s a mechanical engineer and she’s a nurse practitioner. He’s been wanting to play Jude ever since seeing him in a YouTube video.

“As you see, I get to meet dynamite women,” Jude says, directing his comment to Nikki.

Nikki and Stephen hold hands the entire time they sit at the table. As he plays Stephen, Jude quizzes Nikki about their marriage. How did you meet? Did he make his move fast? How did he propose? Did he chase after you?

This is not the conversation that Nikki expected. “He never had to. He’s a very nice person.”

Then Jude looks hard at the board. “I have given you all my positional traps,” he says to Stephen. “You have avoided them all.”

He looks some more. “You’re doing tremendously well.”

He pauses. “The reason I’m taking my time is I don’t have a clear plan and it does bother me.”

Jude goes back to Nikki.

“When you were a kid, when did you realize you had a lot of confidence?”

“I don’t know if I ever did.”

Jude returns to the board. He has a knight and a rook while Stephen has two bishops. Jude has also gained a pawn.

But Jude isn’t sure where to take it from here. The game slows to a crawl. Stephen checks his watch in the manner of someone who has dinner reservations on a Friday night in New Orleans and whose wife is patiently waiting for a chess game to end.

Jude puts on his jacket. Body temperature is important for a professional player.

4:27 p.m.

The game goes on. Jude narrates his thoughts.

“I would like my pawns to go down the board, but I still have to work.” He looks at Stephen. “I’m very proud of you.”

Stephen asks how he could have protected the lost pawn. “Just protect it,” Jude says.

Jude now seems to be mainly talking to himself as he tries to finish the game. “Keep it simple,” he says. “Don’t try to be a hero.”

4:40 p.m.

Stephen checks his watch again.

4:49 p.m.

Another cluster of college students has arrived. They are holding drinks and are more wobbly than the Vanderbilt students. The one in front is wearing a pink shirt, a few Mardi Gras beads, and has “Proverbs 33:6” tattooed up his arm.

“Do you take Venmo?”

“Cash only.”

“I only have three dollars and 75 cents.”

Jude goes back to his pawns.

The challenger sways a bit more, “Dude. How about if I win, I don’t pay. If you win, I’ll pay.”

Jude ignores him.

“Just tell me what your first move would be.”

Silence.

The would-be challenger drifts to the side of the table and watches for a while. Then he tries again.

“What’s your first move?”

I can’t take it any longer. “His first move is to be paid five dollars,” I say quietly.

The challenger looks puzzled, as if seeing me for the first time. He and his friends soon lose themselves in a growing Mardi Gras crowd.

5:09 p.m.

Jude finally advances his pawns, ending the game. Somehow, Jude convinces Nikki to stand on top of his table for a photo. We all help her up and then down.

“Those photos are for World Wide Media!” Jude tells her.

Stephen and Nikki depart, Nikki likely wondering what just happened, Stephen possibly still thinking about that lost pawn.

5:20 p.m.

Jude abruptly disappears across Decatur.

5:30 p.m.

“Dinner is served!”

Jude walks confidently through the slow line of cars on Decatur Street, carrying two plastic shopping bags. He takes out Styrofoam containers of gumbo, macaroni and cheese, and fried potatoes.

Jude says his relationship with French Market Seafood really took off in the days that followed Hurricane Katrina and the city’s levee breaks. Along with other journalists across the country, I had covered the story of Jude’s days in the French Quarter as water rose in nearby neighborhoods. He narrates the events that followed, slipping into third person:

“Jude is all alone, pulls his table out, the only people around were Red Cross workers. Mr. Marullo is passing out menus. Jude, with his beginner kitchen skills, started to help him clean up. Says Mr. Marullo: ‘You really helped us out. You’re eating in my restaurant free.’”

A man leans out his car window. “There’s the champ for life!” he shouts.

Jude waves his arm.

“With the food, the people, where I am,” he says. “I know I am a millionaire.”

5:57 p.m.

The street lamp over the World Chess Table turns on for the night.

5:58 p.m.

The table is quiet. It’s littered with newspapers, gumbo containers, and Young Upstart’s beer cans. No more players arrive. Jude begins a new story, then stops himself. He waves his arms around like propellers. “Yes! Yes!” he shouts.

Baylee Badawy leans in and sets a Mardi Gras king cake on the table. She doesn’t leave for Las Vegas until tomorrow, she explains. The two catch up on the latest news. They talk about the table and how it is still standing after five years of street play, which makes it a miracle table. They talk about when Hikaru Nakamura visited the Chess Cave, and they talk about the viral Jude Acers posts that Baylee has made. They talk about everything and nothing, the way only best friends can talk.

“No funeral when I die,” Jude says. “I want to be buried in the Louisiana swamp with a big party where people are telling Jude Acers stories.”

On the other side of Canal Street, parades are lining up, kicking off the start of the last weekend of Carnival. But Baylee, who also lives in the French Quarter, is on her way home. “Jude always walks me back,” she says.

The table not yet locked down, they disappear down Decatur, keeping to the center of streets, never crossing at crosswalks, walking arm and arm into a perfect French Quarter night.

Categories

Archives

- January 2026 (8)

- December 2025 (27)

- November 2025 (29)

- October 2025 (39)

- September 2025 (27)

- August 2025 (29)

- July 2025 (43)

- June 2025 (25)

- May 2025 (24)

- April 2025 (29)

- March 2025 (29)

- February 2025 (20)

- January 2025 (24)

- December 2024 (34)

- November 2024 (18)

- October 2024 (35)

- September 2024 (23)

- August 2024 (27)

- July 2024 (44)

- June 2024 (27)

- May 2024 (31)

- April 2024 (51)

- March 2024 (34)

- February 2024 (25)

- January 2024 (26)

- December 2023 (29)

- November 2023 (26)

- October 2023 (37)

- September 2023 (27)

- August 2023 (37)

- July 2023 (47)

- June 2023 (33)

- May 2023 (37)

- April 2023 (45)

- March 2023 (37)

- February 2023 (28)

- January 2023 (31)

- December 2022 (23)

- November 2022 (32)

- October 2022 (31)

- September 2022 (19)

- August 2022 (39)

- July 2022 (32)

- June 2022 (35)

- May 2022 (21)

- April 2022 (31)

- March 2022 (33)

- February 2022 (21)

- January 2022 (27)

- December 2021 (36)

- November 2021 (34)

- October 2021 (25)

- September 2021 (25)

- August 2021 (41)

- July 2021 (36)

- June 2021 (29)

- May 2021 (29)

- April 2021 (31)

- March 2021 (33)

- February 2021 (28)

- January 2021 (29)

- December 2020 (38)

- November 2020 (40)

- October 2020 (41)

- September 2020 (35)

- August 2020 (38)

- July 2020 (36)

- June 2020 (46)

- May 2020 (42)

- April 2020 (37)

- March 2020 (60)

- February 2020 (38)

- January 2020 (45)

- December 2019 (34)

- November 2019 (35)

- October 2019 (42)

- September 2019 (45)

- August 2019 (56)

- July 2019 (44)

- June 2019 (35)

- May 2019 (40)

- April 2019 (48)

- March 2019 (61)

- February 2019 (39)

- January 2019 (30)

- December 2018 (29)

- November 2018 (51)

- October 2018 (45)

- September 2018 (29)

- August 2018 (49)

- July 2018 (35)

- June 2018 (31)

- May 2018 (39)

- April 2018 (31)

- March 2018 (26)

- February 2018 (33)

- January 2018 (30)

- December 2017 (26)

- November 2017 (24)

- October 2017 (30)

- September 2017 (30)

- August 2017 (31)

- July 2017 (28)

- June 2017 (32)

- May 2017 (26)

- April 2017 (37)

- March 2017 (28)

- February 2017 (30)

- January 2017 (27)

- December 2016 (29)

- November 2016 (24)

- October 2016 (32)

- September 2016 (31)

- August 2016 (27)

- July 2016 (24)

- June 2016 (26)

- May 2016 (19)

- April 2016 (30)

- March 2016 (36)

- February 2016 (28)

- January 2016 (32)

- December 2015 (26)

- November 2015 (23)

- October 2015 (16)

- September 2015 (28)

- August 2015 (28)

- July 2015 (6)

- June 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (2)

- April 2015 (1)

- February 2015 (3)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- October 1991 (1)

- August 1989 (1)

- January 1988 (1)

- December 1983 (1)